We learn much better if we take notes the old-fashioned way, by hand, and now researchers know more about why this is.

“When we measure the brain activity of people who write by hand, we see that they form more connections in the brain than when they write using a computer,” says brain researcher Audrey van der Meer, a professor of neuropsychology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Writing by hand seems to activate more brain cells, which improves our ability to learn subject matter.

“This year, 20 states in the United States reintroduced handwriting at school,” says van der Meer.

Previously, researchers have also looked at the differences in brain activity when subjects are writing by hand, on a keyboard, or when drawing. They have now delved deeper into which parts of the brain become activated, and how.

“When people write by hand, we see noticeably more nerve activity in the parts of the brain that deal with memory and interpretation of new information. This activity plays a key role in the learning process,” says van der Meer.

The researchers investigated students who wrote using a tablet, both with a digital pen and with a digital keyboard. They contend that the effect is the same as whether you use a regular pen or pencil. It is the formation of the letters that is important.

“When we write by hand, we use more of our senses than we do when we use a keyboard. On a keyboard, we repeat the same simple finger movements regardless of which character we want to type,” says van der Meer’s colleague, Professor Ruud van der Weel.

A 2020 study involving 19 countries showed that Norwegian children aged 9 to 16 spent the most time online of all, with a daily average of four hours. Norwegian 16-year-olds were online six hours a day.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health advises against any screen use for children under the age of 2. For children between the ages of 2 and 5, screen time should be limited to one hour per day. Much of our brain development takes place at a very early age, so parents need to be aware of the risks involved with too much screen time.

“Accurately controlled movements are among the brain’s most important tasks. We can accelerate Norwegian infants’ brain development by providing them with early sensory-motor stimulation through activities such as baby swimming, baby massage, or tummy time.

“Infants can certainly learn a lot from a screen, but they simply cannot afford to spend their valuable time sitting still in front of a screen, as they have so much to learn during the first two to three years of their lives. The youngest children, with their small bodies and plastic brains, need to experience the real world,” says van der Meer.

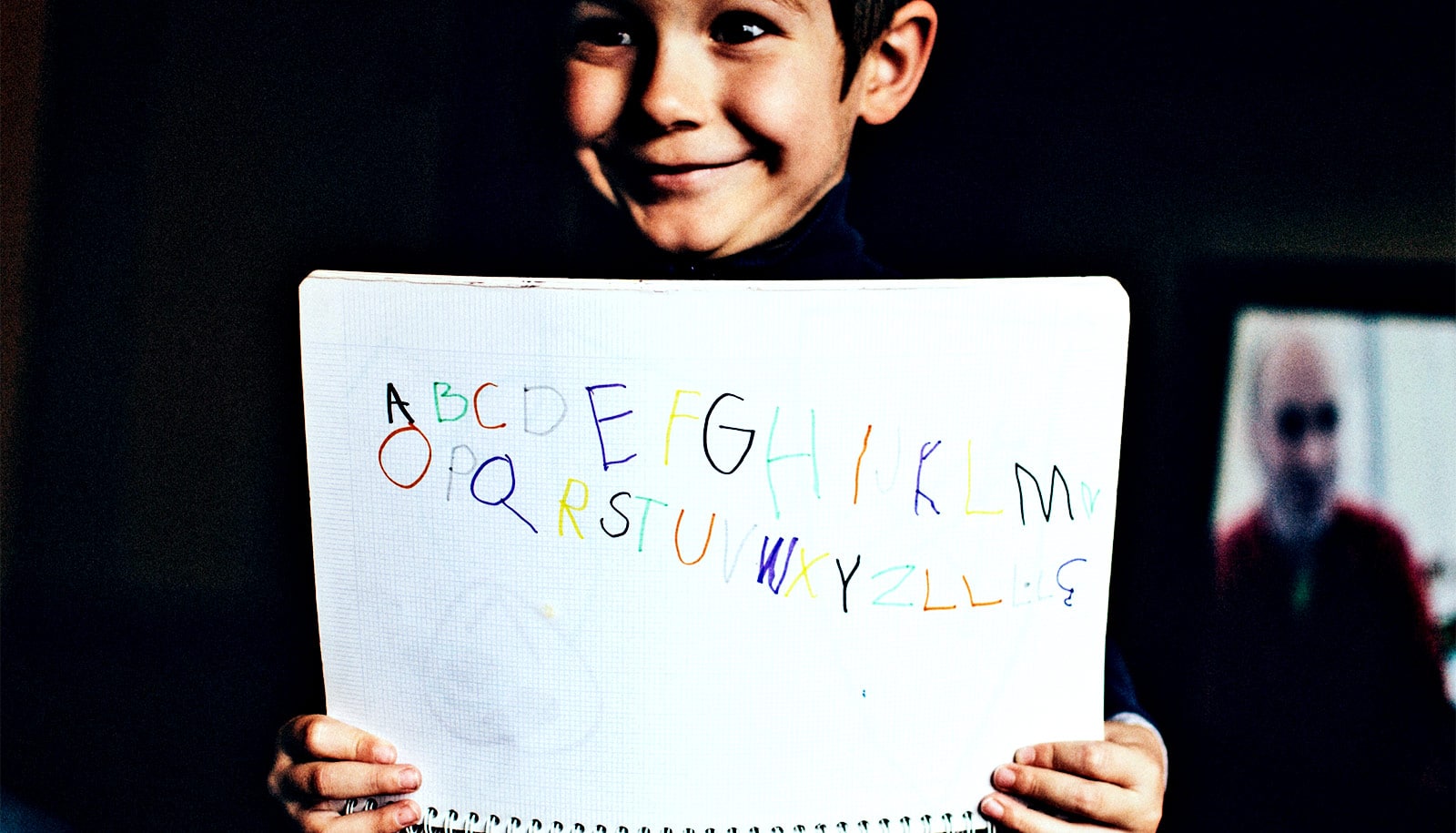

“Children who first learn to write using keyboards often have difficulty distinguishing between letters that are mirror images of each other, like ‘b’ and ‘d’. They haven’t physically experienced how it feels to form these letters,” says van der Weel.

The researchers have a very clear message.

“Preschoolers need to perform activities that require fine motor skills. These might include writing, drawing, coloring, beading, or doing puzzles. Many children barely know how to hold a pen or pencil,” says van der Weel.

“Children must first learn to write by hand, starting from Year 1 of school, so that they can form the neural networks that create the best possible foundation for learning,” says van der Meer.

This is important for handwriting, but also in relation to mastering new technologies later in life. Different tools are suitable for different situations.

“Research shows that pupils learn new information best when they take notes by hand, but it can also be more practical to write longer texts on a computer,” says van der Meer.

The researchers believe that we need to establish rules to ensure that children receive a minimum amount of handwriting practice.

The research appears in Frontiers in Psychology.