A new study outlines a method for detecting wormholes, which form a passage between two separate regions of spacetime.

The speculative phenomenon that has long captured the imagination of sci-fi fans. Such pathways could connect one area of our universe to a different time and/or place within our universe, or to a different universe altogether.

Whether wormholes exist is up for debate, but in a paper in Physical Review D, physicists describe a technique for detecting these bridges.

Stretching stars

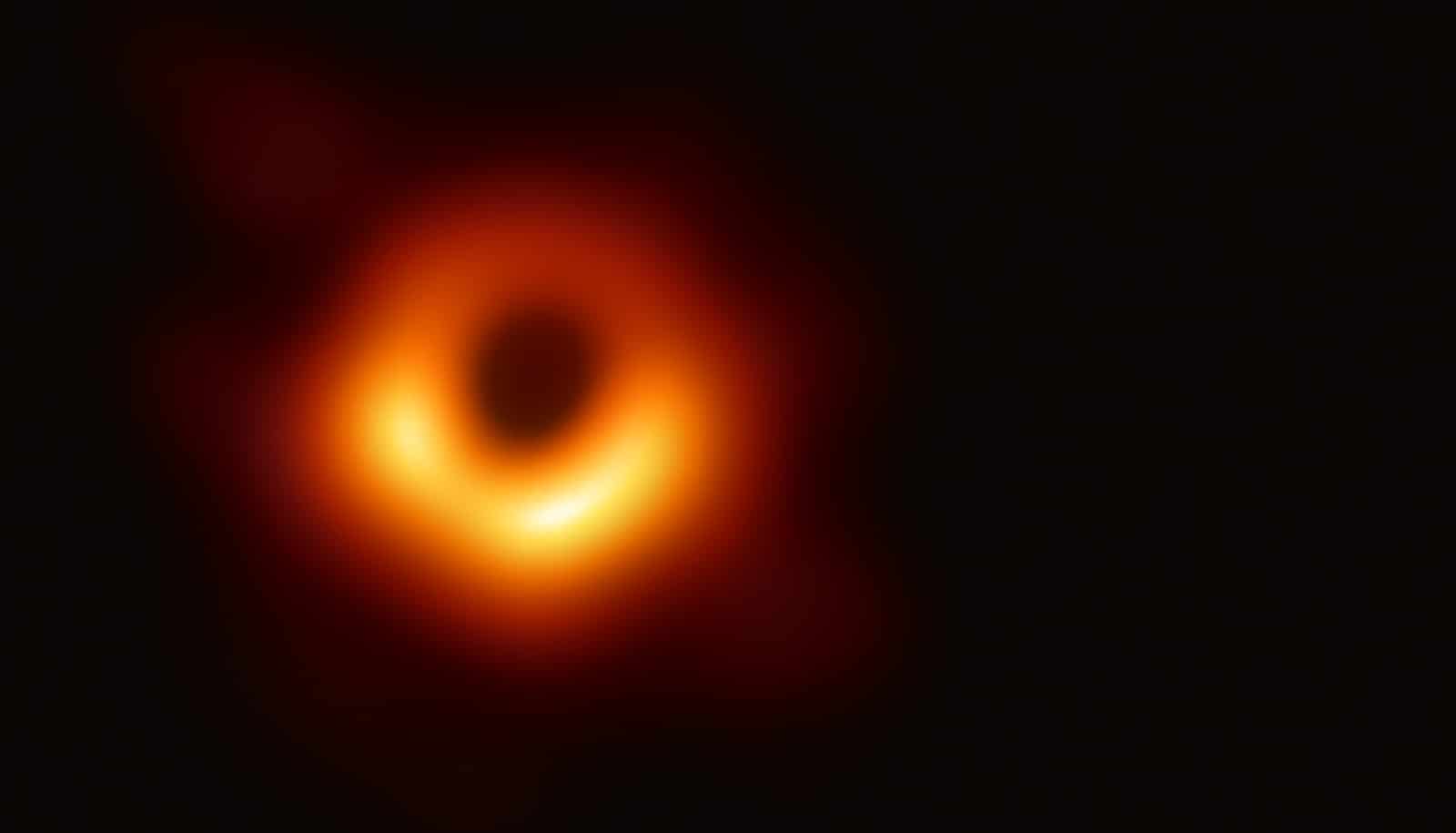

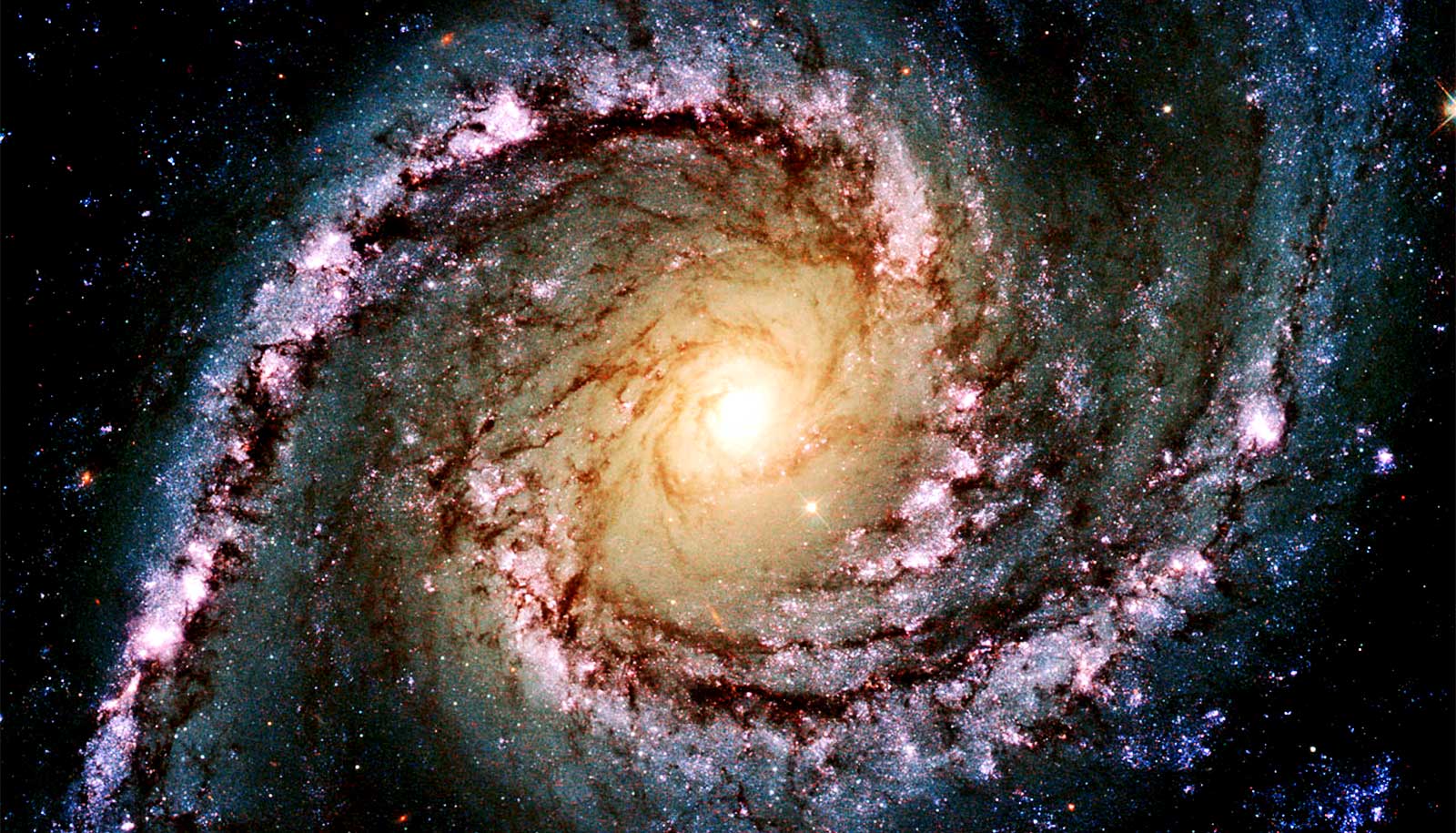

The method focuses on spotting a wormhole around Sagittarius A*, an object that’s thought to be a supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy. While there’s no evidence of a wormhole there, it’s a good place to look for one because wormholes are expected to require extreme gravitational conditions, such as those present at supermassive black holes.

In their paper, the researchers write that if a wormhole does exist at Sagittarius A*, the gravity of stars at the other end of the passage would influence nearby stars. As a result, it would be possible to detect the presence of a wormhole by searching for small deviations in the expected orbit of stars near Sagittarius A*.

“If you have two stars, one on each side of the wormhole, the star on our side should feel the gravitational influence of the star that’s on the other side. The gravitational flux will go through the wormhole,” says Dejan Stojkovic, cosmologist and professor of physics in the University at Buffalo. “So if you map the expected orbit of a star around Sagittarius A*, you should see deviations from that orbit if there is a wormhole there with a star on the other side.”

Not like sci-fi

Stojkovic notes that if wormholes are ever discovered, they’re not going to be the kind that science fiction often envisions.

“Even if a wormhole is traversable, people and spaceships most likely aren’t going to be passing through,” he says. “Realistically, you would need a source of negative energy to keep the wormhole open, and we don’t know how to do that. To create a huge wormhole that’s stable, you need some magic.”

Nevertheless, wormholes—traversable or not—are an interesting theoretical phenomenon to study. While there is no experimental evidence that these passageways exist, they are possible—according to theory. As Stojkovic explains, wormholes are “a legitimate solution to Einstein’s equations.”

Hunting for wormholes

The research focuses on how scientists could hunt for a wormhole by looking for perturbations in the path of S2, a star that astronomers have observed orbiting Sagittarius A*.

While current surveillance techniques are not yet precise enough to reveal the presence of a wormhole, Stojkovic says that collecting data on S2 over a longer period of time or developing techniques to track its movement more precisely would make such a determination possible. These advancements aren’t too far off, he says, and could happen within one or two decades.

Stojkovic cautions, however, that while the new method could help researchers detect a wormhole if one is there, it will not strictly prove that a wormhole is present.

“When we reach the precision needed in our observations, we may be able to say that a wormhole is the most likely explanation if we detect perturbations in the orbit of S2,” he says. “But we cannot say that, ‘Yes, this is definitely a wormhole.’ There could be some other explanation, something else on our side perturbing the motion of this star.”

Though the paper focuses on traversable wormholes, the technique it outlines could indicate the presence of either a traversable or non-traversable wormhole, Stojkovic says. He explains that because gravity is the curvature of spacetime, the effects of gravity are felt on both sides of a wormhole, whether objects can pass through or not.

De-Chang Dai of Yangzhou University in China and Case Western Reserve University is first author of the paper. Support for the work came from the National Science Foundation of China, National Basic Research Program of China, and the Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader program, and the US National Science Foundation.

Source: University at Buffalo