People from countries on both sides of World War II ascribe an inflated weight to their country’s contribution to the war effort, according to new research.

There is another interesting finding. “Russians view World War II very differently than, basically, people from every other country in our study,” says lead author Henry Roediger, a professor in the psychological and brain sciences department at Washington University in St. Louis. “When you ask people to list the top 10 important events, people from China and Australia, and everyone else, they all list Pearl Harbor and D-Day. Russians don’t.

“Well they do list D-Day,” Roediger says, “but they call it the ‘Opening of the Second Front,’ and they see it as relieving some of the pressure on Soviet forces who then drove to Berlin.”

Global survey

In the first part of the study, researchers surveyed 1,338 people, 18 and older, from 11 countries. They received at least 100 usable surveys from natives of eight of the former Allied powers—Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, Russia (as a proxy for the former Soviet Union), the United Kingdom, and the United States—and three former Axis powers—Germany, Italy, and Japan.

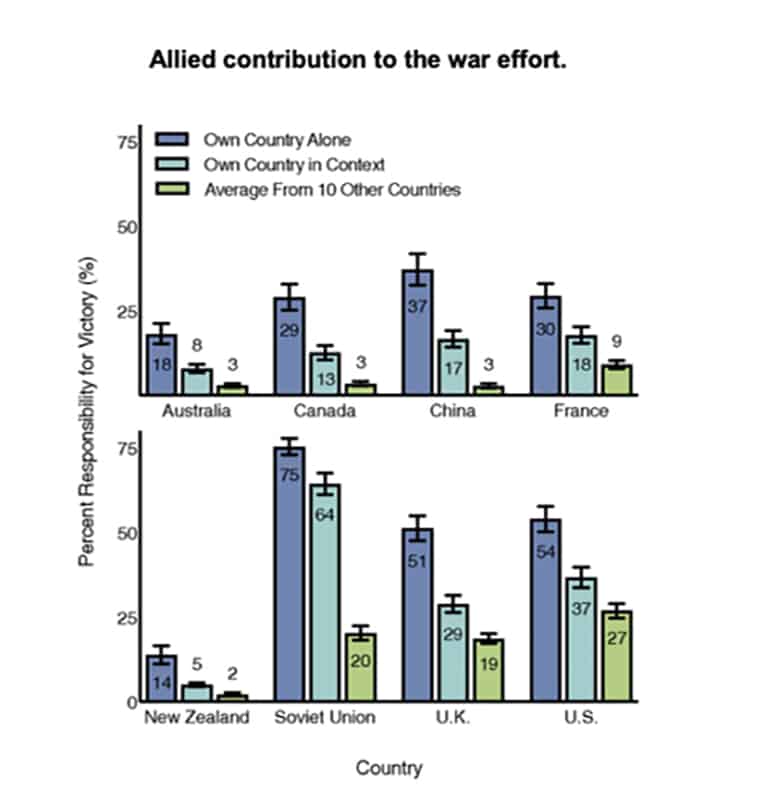

Researchers designed the study to gauge how important people thought their country’s contribution was in the war effort. They asked participants from the Allied countries, “In terms of percentage, what do you think was (your country’s) contribution to the victory in World War II?”

No matter how much a particular country contributed however, the sum total of all losses cannot equal more than 100%. Among just three Allied countries, Russia, the UK, and the US, however, participants claimed their countries contributed 180%. Russians claimed 75%, the UK respondents claimed 51%, and those from the US 54%. Across all eight Allied countries, the total effort amounted to about 300%.

And that’s only eight of the dozens of countries that signed onto the Declaration of the United Nations before the end of the war. According to the National World War II Museum website in New Orleans, 12 additional countries had at least 1,000 military deaths during the war.

Remembering the war differently

“Collective memory refers to the way people remember history, what they believe about it, and these beliefs arise from your background, your society, your education, and your media,” Roediger says. “And, of course, all these influences create the memories about your country as it was involved in World War II.”

Even when researchers changed the question to require respondents to provide estimates for all eight Allied countries as well as other countries, so that their totals had to equal 100% (or less, if they were considering some of the countries not included in the survey), adding the scores that people in a given country gave their own country still totaled more than 191%.

Overestimating one’s contribution is not just a feature of the “winning” side. The researchers asked residents of former Axis countries what percentage of the war effort their country contributed. The German respondents claimed 64%, Japanese 47%, and Italians 29% for a total of 140%.

‘National narcissism’

The results of the study illustrate what Roediger terms “national narcissism.” Although such results may seem esoteric, they have real consequences that we can see all around us.

Take Russia. In this second framing of the question, when respondents had to look at answers for their country alongside other the other seven countries, most people did rate their country’s contribution much lower than in the first question.

Except Russia. Its respondents lowered their estimates just 11%, from 75% to 64%. “They may be right,” Roediger says, “at least for the war in Europe.”

Estimates put the loss of Soviet Union soldiers between 8 million and 11 million. In stark contrast to Time Magazine‘s coverage of D-Day as “24 Hours That Saved the World,” many historians would argue that the Soviet Union played the most important role in the outcome of the war in Europe. Overall, the Soviet Union lost between 22 million and 28 million people in the war, or roughly 14% of its population.

But most students in the US learn the Time Magazine version of the war, both in school and through cultural representations, where the US played the leading role.

“The Russian story is told in practically none of our movies, none of our novels,” Roediger says. “It’s all about us.

“But we can understand how the Soviet Union, now Russia, always sees itself as embattled,” Roediger says. “We see them as aggressive, but they often see themselves in terms of this narrative going back hundreds of years: Russia is minding its own business, it is viciously attacked and looks like it’s going to lose everything, but they come together, against all odds, and win. My coauthor, Jim Wertsch, refers to this script as the Russian narrative template.”

Today, the Russians may see the United States in that same context.

“Now, we have NATO countries that surround them,” Roediger says. “The idea is that if you can understand the historical memory of a people, you can be more successful in understanding their viewpoint and in your negotiations with them.”

The results appear in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.