The Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO) is a “terrible decision,” says Davidson Hamer, a global health and infectious disease expert.

Earlier this month, the Trump administration sent a letter to the United Nations formally notifying them of the United States’ intention to leave the World Health Organization (WHO), after accusing the organization of overly trusting China’s reporting of the extent of the coronavirus outbreak in the early months of the pandemic.

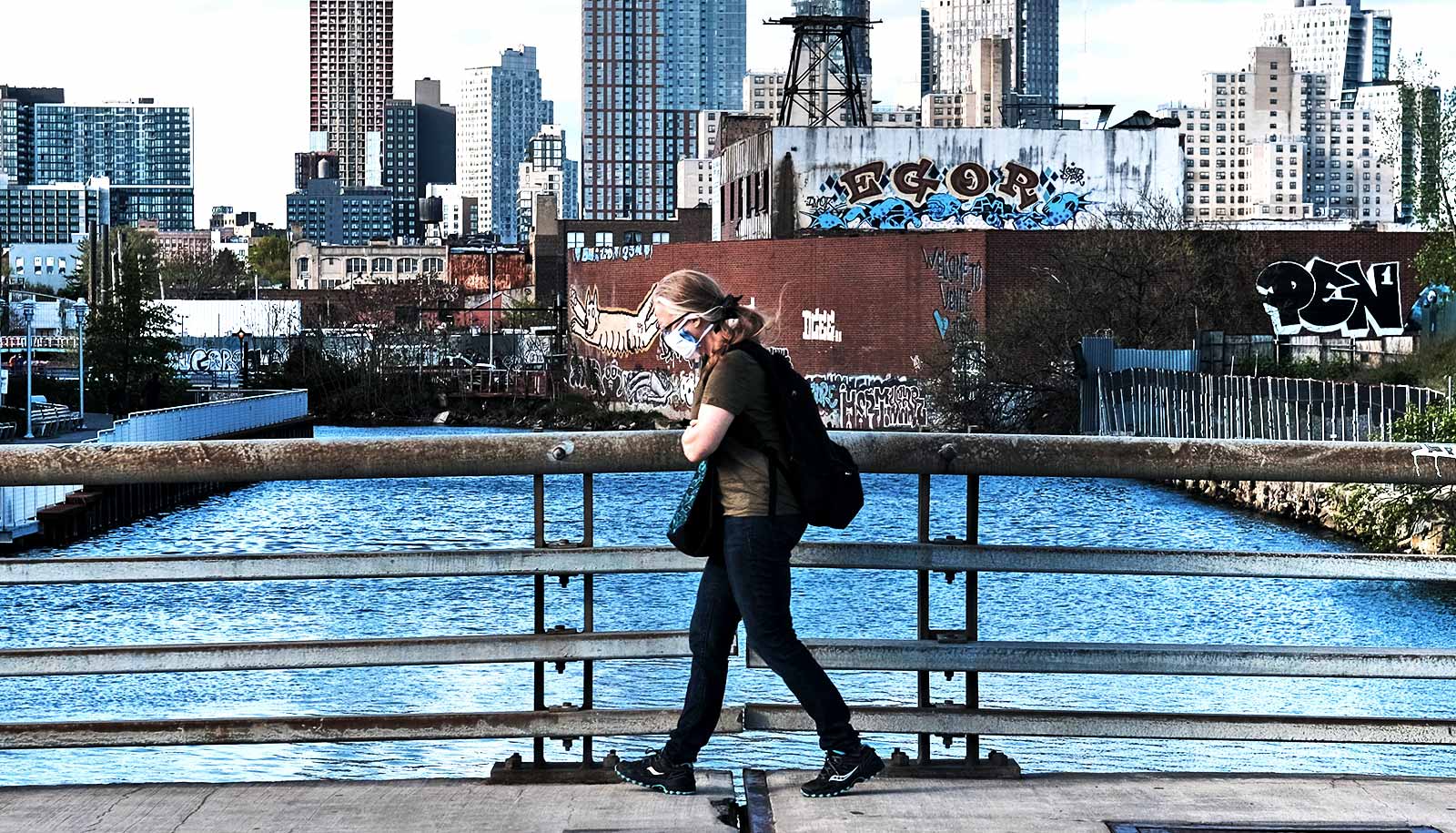

The spread of coronavirus, or COVID-19, infections, is still gripping much of the world and rapidly ballooning to record levels in the United States, which just this week set a record for nearly 76,000 new cases in one day.

“This will have a potential negative impact in terms of controlling diseases, particularly communicable diseases…”

Since the pandemic first began smoldering in China, the WHO has served as central database for the global response to the health crisis. However, the WHO has received criticism for its slowness in updating guidance about the virus as research reveals more information.

The United States has long been one of the largest financial supporters of the WHO, an organization that has helped eradicate smallpox and control and prevent the spread of polio, malaria, HIV, and other diseases that affect some of the world’s most vulnerable.

Trump’s move to withdraw the US from the WHO has prompted many public health leaders to speak out against the decision, which would take effect in July 2021 if finalized.

Hamer, a professor of global health and medicine at Boston University’s School of Public Health and School of Medicine, and a faculty member at the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL), has worked closely with the WHO, serving on various health advisory boards to improve public health guidelines for illnesses such as malaria and childhood fevers.

In recent years, Hamer collaborated with the WHO on a multi-country study to improve the clinical outcomes for sick newborns and has worked on numerous WHO-supported projects focusing on maternal and newborn health in developing nations. He has also been an active part of Boston University’s response to COVID-19, helping to surveil the spread of the virus and educate the community and the public about how COVID-19 transmits within communities and across geographic regions.

Here, Hamer discusses Trump’s plans to pull the United States out of the WHO and why he thinks such a move is “a terrible decision:”

What was your initial reaction to the news of Trump pulling the United States from WHO?

I think there’s a political game behind this, since Trump is stating that the WHO is getting too close to China. The reality is the WHO doesn’t really get too close to any one country, they work with all member states—whether [that be] China or the United States or the Central African Republic, [the WHO] would have to treat them as equal partners.

It’s harder with countries that may be less transparent with their data sharing and so forth. Compared to past situations, I think there was much better transparency about data sharing for the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, certainly than there was for the SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in 2003.

China has been more open with their data sharing [now] and certainly with sharing the [genetic] sequence of the virus. A lot of Trump’s complaints about the WHO are either overblown or not always accurate, and I think there’s also this sort of animosity or competition with China that forms part of [this decision]. In any case, I think it’s a terrible decision.

Are there any positive sides to this decision?

There’s very limited upside to this. I think the only thing is that if we stopped contributing to the WHO budget, we would save that portion of money. But that’s a pretty weak positive.

Right, let’s talk about the negatives.

To start, the WHO serves many functions, including central data collection and monitoring for the world, so it’s a central repository of information and source for reportable diseases. They develop helpful guidelines and policies that are used throughout the world, and a lot of those are for low- to middle-income countries. If it’s not able to do its job well, the repercussions go beyond just the countries that are having measles outbreaks (recently including the United States, for example), it means the rest of the world is at risk.

There’s also a lot of collaboration between the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that could be harmed by not working with them, or result in not being able to work with them as effectively as we have in the past for [understanding transmission], disease control, disease prevention, policy development, and so forth. That’s extremely important for controlling diseases worldwide.

How can this impact the US ability to respond to disease outbreaks, like we’re experiencing right now?

The WHO is really at the center of trying to coordinate the global response to COVID-19. If we are not working with them to help with this, we’re not going to benefit as much from potential evidence generated by the WHO, nor can we influence efforts in a positive way by helping share useful evidence we gathered in the United States, [which] can help strengthen policies and programs and guidelines. It’s a terrible time to do this, in the middle of a pandemic.

How have you worked with WHO?

The BU School of Public Health has been involved with the WHO for the treatment of pneumonia in children. I’ve also worked on a similar project for improving the care of sick young infants in the first to two months of their lives. We did a study in collaboration with the Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child, and Adolescent Health of the WHO, which does a lot of really great research that leads to evidence that changes policies and guidelines worldwide. Just today, we signed a contract with the WHO to start an in-depth review of childhood diarrhea, and everything related to its assessment, treatment, and prevention.

It’s a short-term project, and we’ll be looking at various data sources to estimate how many children are dying from diarrhea each year from a number of causes, [including] bacterial and viral infections, dehydration, malnutrition, and metabolic complications.

One other thing that is important to mention is that one of the functions of the WHO is putting together evidence review groups. They bring in experts to listen to presentations on a certain topic, discuss the evidence, and [the WHO] will use members of that group in an advisory group that will then help define, design, and revise health guidelines. A couple years ago, I was a part of an advisory group to revise their guidelines for treatment of malaria during pregnancy. We revised them based on new data and that became the global policy for treatment. The WHO has a well-developed approach [to establishing evidence-based health guidelines].

How do you think the WHO has handled COVID-19?

Largely, they’ve done a good job. There may have been some delays [communicating] the seriousness of the outbreak in China. Once they did, they sent a team to investigate and help the Chinese government, and the WHO has developed a central dashboard and a daily situational report that tracks the state of the epidemic worldwide. [The WHO has] put out guidance on different aspects of prevention in particularly low-income countries and middle-income countries that don’t have the resources to scale up testing.

Are there any immediate consequences from the United States withdrawing from the WHO, especially if the pandemic continues to spread over the next year?

If we pull out all of our financial support, [it’s especially] going to hurt a lot of the programs that are implemented in low-income countries. This will have a potential negative impact in terms of controlling diseases, particularly communicable diseases, and so could have a negative impact for the health of populations in many parts of the world, and the potential for travel-related introduction [of diseases] into the United States.

We have a population that’s been suffering from vaccine hesitancy for a while, and so [we’re lacking] adequately high levels of vaccine coverage for diseases like measles in certain populations. The potential for [spread between countries] is great, and [that’s what] the WHO helps to control.

What do you hope will happen in the next year, regarding the US relationship with WHO?

I am cautiously optimistic that we will have a change of presidency and we will have a Democratic president who will reverse the decision that’s been made to leave the WHO. We have a year before that is finalized and that means whoever the president is in January will be making the final decision.

My biggest hope is that the plan to pull out [from the WHO] is reversed and that we continue to make major contributions both to its financial operations, but also [in providing] scientific support to the WHO, whether through the CDC or academic research, and that we continue to help it do its job effectively, both for controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, but also [the WHO’s] routine efforts with malaria, tuberculosis, drug resistance, and a variety of noncommunicable diseases.

Source: Boston University