A new wireless transceiver boosts radio frequencies into 100-gigahertz territory, quadruple the speed of the upcoming 5G, or fifth-generation, wireless communications standard, researchers report.

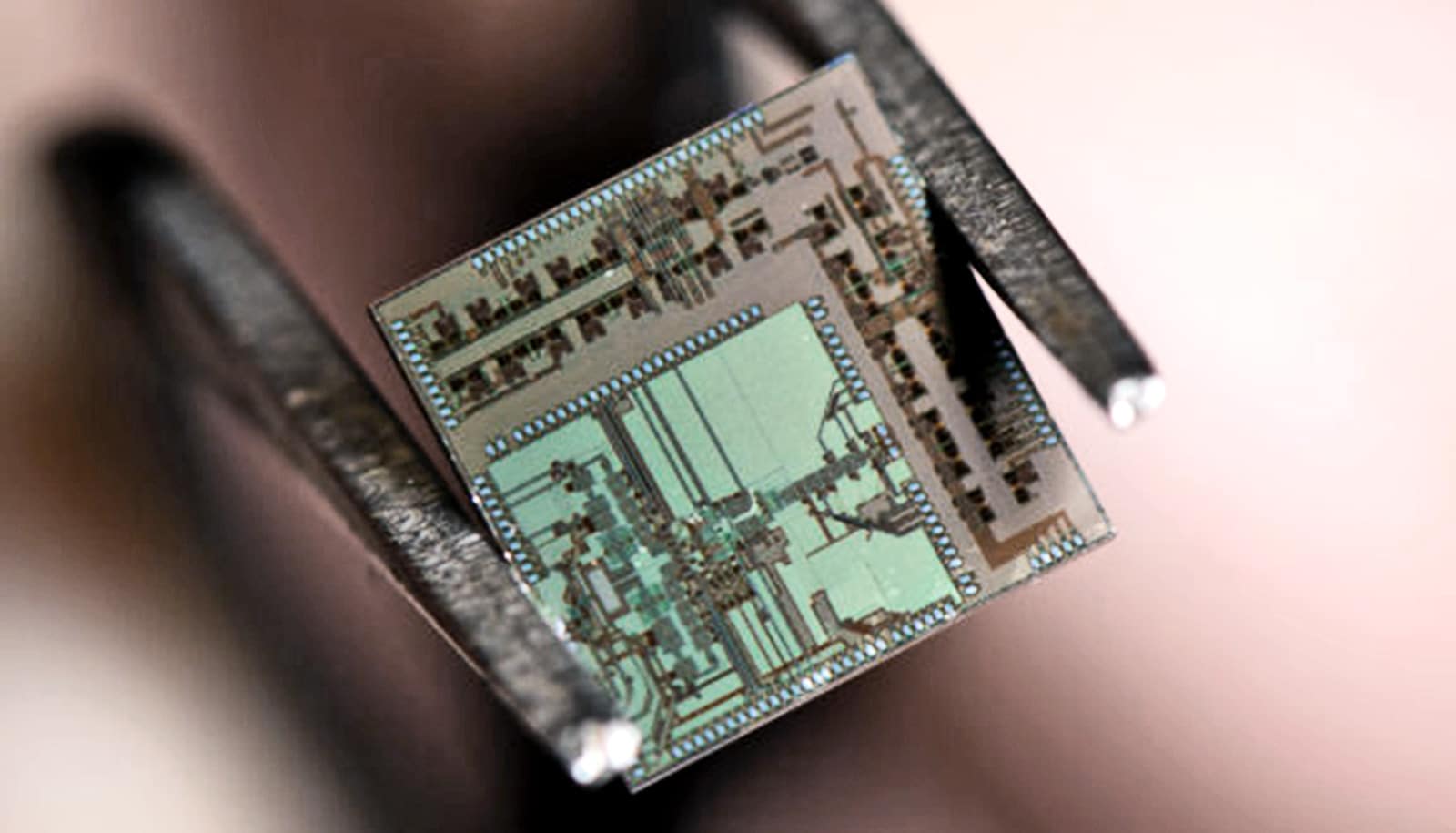

Labeled an “end-to-end transmitter-receiver” by its creators in the University of California, Irvine’s s Nanoscale Communication Integrated Circuits Labs, the 4.4-millimeter-square silicon chip is capable of processing digital signals significantly faster and more energy-efficiently because of its unique digital-analog architecture.

“We call our chip ‘beyond 5G’ because the combined speed and data rate that we can achieve is two orders of magnitude higher than the capability of the new wireless standard,” says senior author Payam Heydari, NCIC Labs director and a professor of electrical engineering & computer science. “In addition, operating in a higher frequency means that you and I and everyone else can be given a bigger chunk of the bandwidth offered by carriers.”

Building a better transceiver

Heydari says that academic researchers and communications circuit engineers have long wanted to know if wireless systems are capable of the high performance and speeds of fiber-optic networks.

“If such a possibility could come to fruition, it would transform the telecommunications industry, because wireless infrastructure brings about many advantages over wired systems,” Heydari says.

His group’s answer is in the form of a transceiver that leapfrogs over the 5G wireless standard—designated to operate within the range of 28 to 38 gigahertz—into the 6G standard, which is expected to work at 100 gigahertz and above.

“The Federal Communications Commission recently opened up new frequency bands above 100 gigahertz,” says lead author and postgraduate researcher Hossein Mohammadnezhad, a graduate student at the time of the work who has since earned a PhD in electrical engineering & computer science. “Our new transceiver is the first to provide end-to-end capabilities in this part of the spectrum.”

The future of wireless networks

Having transmitters and receivers that can handle such high-frequency data communications is going to be vital in ushering in a new wireless era dominated by the “internet of things,” autonomous vehicles, and vastly expanded broadband for streaming of high-definition video content and more.

While this digital dream has driven technology developers for decades, stumbling blocks have begun to appear on the road to progress. According to Heydari, scientists have traditionally changed frequencies of signals through modulation and demodulation in transceivers via digital processing, but integrated circuit engineers have in recent years begun to see the physical limitations of this method.

“Moore’s law says we should be able to increase the speed of transistors—such as those you would find in transmitters and receivers—by decreasing their size, but that’s not the case anymore,” he says. “You cannot break electrons in two, so we have approached the levels that are governed by the physics of semiconductor devices.”

To get around this problem, the researchers utilized a chip architecture that significantly relaxes digital processing requirements by modulating the digital bits in the analog and radio-frequency domains.

Heydari says that in addition to enabling the transmission of signals in the range of 100 gigahertz, the transceiver’s unique layout allows it to consume considerably less energy than current systems at a reduced overall cost, paving the way for widespread adoption in the consumer electronics market.

The technology combined with phased array systems—which use multiple antennas to steer beams—facilitates a number of disruptive applications in wireless data transfer and communication, says coauthor Huan Wang, a doctoral student in electrical engineering & computer science and an NCIC Labs member.

“Our innovation eliminates the need for miles of fiber-optic cables in data centers, so data farm operators can do ultra-fast wireless transfer and save considerable money on hardware, cooling, and power,” he says.

A paper on the transceiver appears in the Journal of Solid-State Circuits.

TowerJazz and STMicroelectronics provided semiconductor fabrication services to support this research project.

Source: UC Irvine