In many cases, the massive wildfires that burned in California, Oregon, Montana, Idaho, British Columbia, and other parts of North America in 2017 exhibited a disturbing trend: a marked increase in the amount of area burned. That trend will continue in coming decades across the western US and northwestern Canada, though not uniformly, a new study suggests.

“…the large fire seasons of recent years, such as the one just ending, are likely to occur more frequently…”

The Thomas Fire, which consumed 281,893 acres in California’s Santa Barbara and Ventura counties in December, was the largest in the state’s history. The Nazko Complex Fire in British Columbia burned more than 1 million acres, the largest ever recorded for the province.

While it may have been an exceptional year in some respects, the researchers’ predictions suggest that years like 2017 are likely to become more common over time. States in the interior Western US, in particular, may face large increases in total wildfire area burned, potentially beyond anything that they have experienced in the past.

The results of the study, which appear in the journal PLOS ONE, project where the greatest increases in area burned are likely to occur across the western US and Canada in coming decades, suggesting that large fires years such as the recent ones in southern and northern California may become more common.

Future wildfires

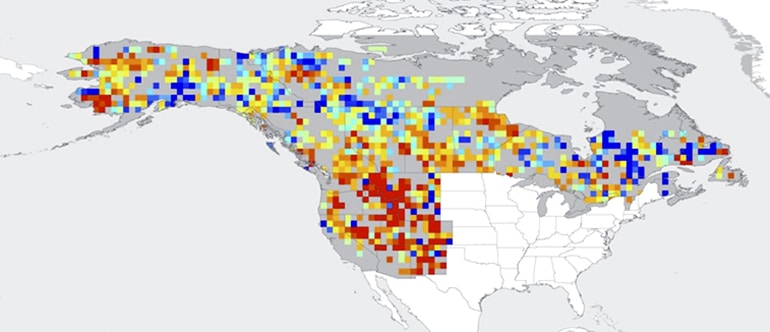

“We used 34 years of climate data to calibrate area burned in 1,500 grid cells across western North America, so we could capture the different ways that seasonal climate regulates fire in different regions,” says Don Falk, a professor in the School of Natural Resources and the Environment in the University of Arizona’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

The key measurement, annual area burned, is a combination of fire size, frequency, and variability from year to year. Area burned does not necessarily indicate fire severity, the ecological effects in a burned area.

Taking into account geographic variation, the study data focused on fire occurrence, seasonal temperatures, and snowpack. Summer temperatures during fire season, spring temperatures and rainfall, and winter temperatures were the seasonal climate variables that turned out to be driving the amount of area burned. Winter and spring conditions regulate snowpack, which can delay the onset of the fire season.

The team built a statistical model for wildfire area burned in each of the grid cells they studied, and then tested it with data for actual area burned since 2010 to validate their predictions. It did not project the extent of area burned beyond the mid-21st century, as climate and vegetation changes become more uncertain later in the century.

The findings for western and northern North America project that about half the states and provinces will have a large increase—five or more times the current levels—in total wildfire area burned. Others may see smaller increases, indicating there is no “one-size-fits-all” model. Increases in area burned are unevenly distributed across the study area, with the strongest increases projected in the interior western region.

‘A wake-up call’

“Ultimately, this means that the large fire seasons of recent years, such as the one just ending, are likely to occur more frequently, affecting ecosystems, communities, and public safety,” Falk says. “These will be billion-dollar fire years. We’re just not ready for fire impacts of this kind, including post-fire effects from flooding after fire.”

How frequent fires change ecosystems over time

Experts project that the total cost of the 2017 fires in California alone will exceed $180 billion. This includes not only the immediate costs of firefighting, but also the much larger costs of landscape rehabilitation; medical and hospital costs; insurance losses and the costs of replacing thousands of homes and other buildings; lost economic productivity from the destruction of businesses; repair and replacement of key infrastructure such as roads, power lines, and dams; and weeks of lost income by employees.

Across the US, public land managing agencies are being stretched to their limits by the current scale of wildfire. The US Forest Service spends more than half of its entire budget on wildfire response, leaving little for other key elements of its mission such as recreation, ecosystem restoration, research, and public education.

Knowing about future regional variation in the projected annual area burned can help land managers and policy makers prepare for the possibility of extremely large fire years. Falk points out that seasonal climate changes are also having the effect of making the fire season longer, so there is additional time for more acreage to burn. In years when seasonal climate drives lengthy fire seasons, fire management resources may be stretched to the limit.

“Wildfires act as a multiplier of other forces such as climate change, exposing more and more areas not only to the immediate effects of fire, but also to the resulting cascade of ecological, hydrological, economic, and social consequences,” Falk says. “We hope that this research will be a wake-up call to public agencies and legislatures at all levels of government that the fire problem is not going to get any smaller in coming decades.

How climate affects the frequency of wildfires

“If anything, we need a serious, fact-based national dialogue about how to sustain our forests and woodlands through smart management and policy.”

Researchers from the Universidad Nacional del Comahue in Argentina and the University of California, Merced also contributed to the study.

Source: Susan McGinley for University of Arizona