A new study takes a big-picture look at what climate change could mean for wildfires in the Northwest.

Many have questioned what the fires—including the Carlton Complex Fire in 2014, the largest in Washington’s history; the 2017 fire season in Oregon; and the 2018 Maple Fire on the Olympic Peninsula—will mean for the region’s future.

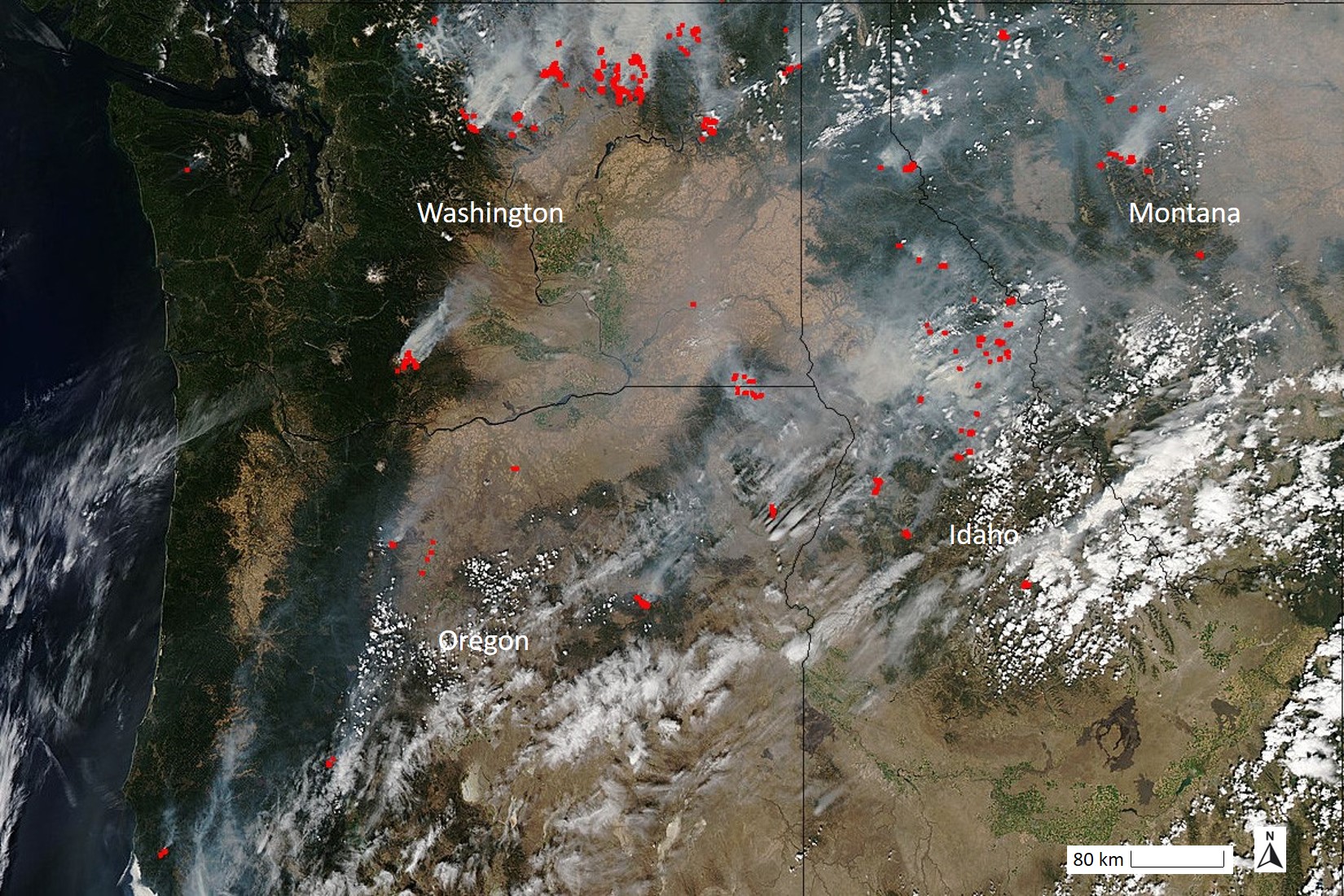

For the study in Fire Ecology, researchers considered wildfires in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and western Montana.

“We can’t predict the exact location of wildfires, because we don’t know where ignitions will occur,” says lead author Jessica Halofsky, a research scientist at the University of Washington School of Environmental and Forest Sciences and with the US Forest Service.

“But based on historical and contemporary fire records, we know some forests are much more likely to burn frequently, and models can help us determine where climate change will likely increase the frequency of fire.”

Big changes for wildfires

Researchers did their review in response to a survey of stakeholder needs from the Northwest Climate Adaptation Science Center, a federal-university partnership. State, federal, and tribal resource managers wanted more information on the available science about fire and climate change.

“We’re on the cusp of some big changes. We expect that droughts will become more common, and the interaction of climate and fire could look very different by the mid-21st century,” says David Peterson, professor at the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. “Starting the process of adapting to those changes now will give us a better chance of protecting forest resources in the future.”

The greatest increased risk was found for low-elevation ponderosa pine forests, of the type found at lower elevations on the east side of the Cascade Range in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and Idaho.

This ecosystem has the highest fire risk today and also has the highest increase in risk due to climate change. The authors predict with high confidence that wildfires in this region will become larger and more frequent.

“We can’t attribute single fire events to climate change. But the trends in large fire events that have been occurring in the region are consistent with expected trends in a warming climate,” says coauthor Brian Harvey, assistant professor at the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. His research group studies forests and fires in the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies.

Drought, heat, and insects

The authors also summarize how other Northwest ecosystems might experience the combined threats of drought, warmer temperatures, and insect outbreaks. Moist, coniferous forests—found on the Olympic Peninsula, in Western Washington, and in Northern Idaho—will likely burn more often, but fires won’t be significantly larger than they were historically.

Fires in subalpine, high-elevation forests, found in mountainous terrain, will similarly become more frequent but only slightly larger or more severe.

After describing the threats, the authors evaluate potential strategies to prepare. Land managers could remove dry organic material, or fuels, and maintain forest densities at lower levels to reduce the severity of fires, since the severity of wildfire is more controllable than the frequency or total area burned.

Thinning would also help the remaining trees to withstand drought. Planting genetically diverse seedlings could also help with regeneration after fires—an important step for long-term survival of forests.

Rural landowners can also play a role, the authors write.

“Individual landowners can reduce hazardous fuels, promote species that can survive fire and drought, and increase diversity of species and structures across the landscape,” Peterson says.

Historically the Northwest has had lower risk of wildfire than other states, such as California, but that may change.

“In general, the climate in the Northwest is cooler and wetter than in most low-elevation areas of California,” Halofsky says. But the Northwest summers are dry and warm. Climate change will accentuate dry summers, and Northwest climate will become more similar to current-day California climate, leading to more and bigger fires.”

The US Department of the Interior and the US Forest Service funded the work.

Source: University of Washington