A newly named fossil whale, Maiabalaena nesbittae, provides information about the evolution of baleen, the filter-feeder system inside the mouths of certain whales, according to new research.

For some time, researchers have known that the ancestors to mysticete whales had teeth. But what hasn’t been clear is how the transition from feeding with teeth to filter feeding with baleen took place.

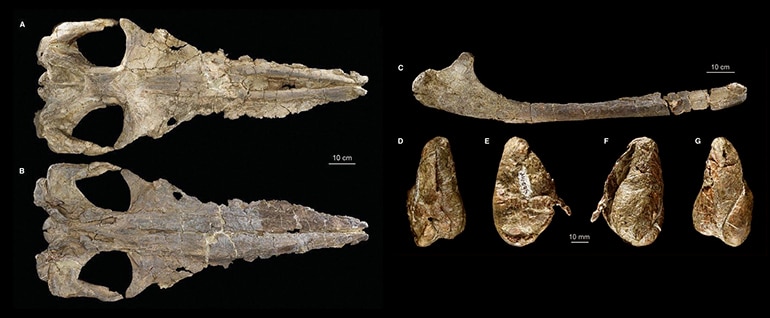

While there have been several competing theories—such as whales filtering with teeth, or whales having teeth and baleen at the same time—this new discovery points in a different direction entirely. Maiabalaena nesbittae appears to have been in a stage of evolution between teeth and baleen, with neither present, the research team believes.

Whales are divided into toothed whales (odontocetes) that chase and capture their prey with their teeth and baleen whales (mysticetes) that strain or filter the water to capture smaller prey such as plankton and krill. Baleen is a unique feature among animals. It is made of keratin, the same material as your fingernails. Baleen plates have hair-like fringes on one side. When hundreds of plates are stacked together they form a filter.

This new whale species, Maiabalaena, shows that early mysticetes experienced tooth loss prior to evolving baleen.

The next obvious question is, “How did it feed?” The answer can be found among living whales that have few functional teeth and use suction to feed. In fact, suction is an ancestral feeding strategy for most marine vertebrates (animals with backbones, like fish). In fact, Maiabalaena has many anatomical aspects that support a suction feeding strategy.

“This discovery is a big deal for us,” says study coauthor Christopher Marshall, a professor in the marine biology department at Texas A&M University at Galveston.

“It’s filled an important gap in understanding the evolution of baleen and filter feeding. Understanding the pattern of how baleen evolved in mysticetes is as important as other major evolutionary transformations such as scales to feathers in birds. Such anatomical transformations fundamentally altered the natural history of baleen whales.”

The findings appear in the journal Current Biology.

Researchers from George Mason University and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History also contributed to the study.

Source: Texas A&M University