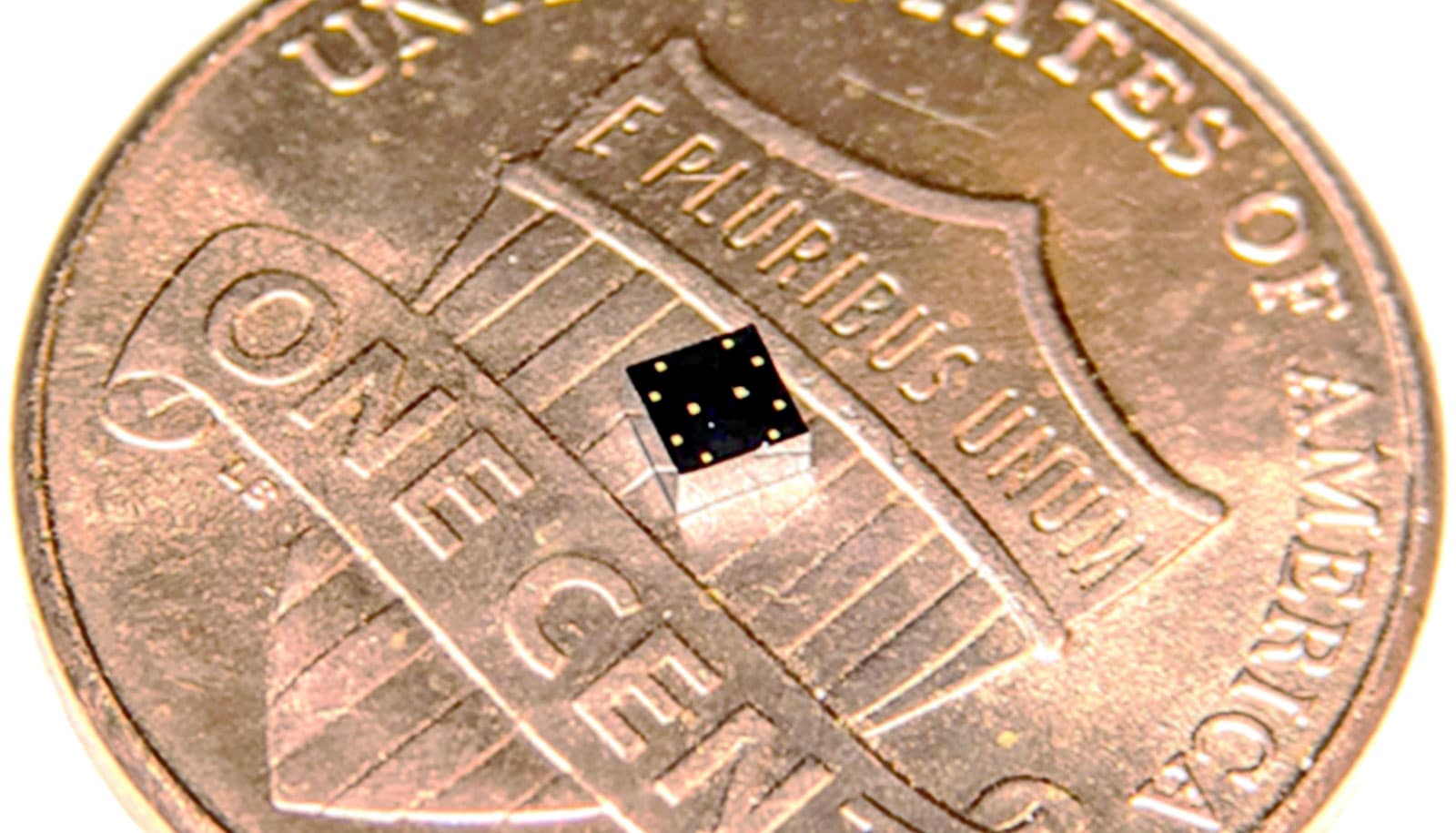

A new wearable sensor is so cheap and simple to produce it can be hand-drawn with a pencil onto paper treated with sodium chloride.

The sensor could clear the way for wearable, self-powered monitors to predict major health concerns like cardiac arrest and pneumonia. And it could even let you know when your baby’s diaper needs a change.

“Our team has been focused on developing devices that can capture vital information for human health,” says Huanyu “Larry” Cheng, associate professor of engineering science and mechanics at Penn State and lead author of the study in the journal Nano Letters. “The goal is early prediction for disease conditions and health situations, to spot problems before it is too late.”

The paper describes the design and fabrication process for a reliable, hand-drawn electrode sensor created using a pencil, drawn on paper treated with a sodium chloride solution. The hydration sensor is highly sensitive to changes in humidity and provides accurate readings over a wide range of relative humidity levels, from 5.6% to 90%.

Simple and quick sensor

Research into wearable sensors has been gaining momentum because of their wide-ranging applications in medical health, disaster warning, and military defense, Cheng explains.

Flexible humidity sensors have become increasingly necessary in health care, for uses such as respiratory monitoring and skin humidity detection, but it is still challenging to achieve high sensitivity and easy disposal with simple, low-cost fabrication processes, he adds.

“We wanted to develop something low-cost that people would understand how to make and use—and you can’t get more accessible than pencil and paper,” says Li Yang, professor in the School of Artificial Intelligence at Hebei University of Technology in China.

“You don’t need to have some piece of multi-million-dollar equipment for fabrication. You just need to be able to draw within the lines of a pre-drawn electrode on a treated piece of paper. It can be done simply and quickly.”

The device takes advantage of the way paper naturally reacts to changes in humidity and uses the graphite in the pencil to interact with water molecules and the sodium chloride solution. As water molecules are absorbed by the paper, the solution becomes ionized and electrons begin to flow to the graphite in the pencil, setting off the sensor, which detects those changes in humidity in the environment and sends a signal to a smartphone, which displays and records the data.

Essentially, drawing on the pre-treated paper within pre-treated lines creates a miniaturized paper circuit board. The paper can be connected to a computer with copper wires and conductive silver paste to act as an environmental humidity detector.

Smart diapers and masks

For wireless application, such as “smart diapers” and mask-based respiration monitoring, the drawing is connected to a tiny lithium battery which powers data transmission to a smartphone via Bluetooth.

For the respiration monitor, the team drew the electrode directly on a solution-treated face mask. The sensor easily differentiated mouth breathing from nose breathing and was able to classify three breathing states: deep, regular, and rapid.

Cheng explains that the data collected could be used to detect the onset of various disease conditions, such as respiratory arrest and shortness of breath and provide opportunities in the smart internet of things and telemedicine.

He adds that respiratory rate is a fundamental vital sign and research has shown it to be an early indicator of a variety of pathological conditions such as cardiac events, pneumonia, and clinical deterioration. It can also indicate emotional stressors like cognitive load, heat, cold, physical effort, and exercise-induced fatigue.

Compared with breath, the human skin exhibits a smaller change in humidity, but the researchers were still able to detect changes using their pencil-on-paper humidity sensor, even after test subjects applied lotion or exercised. Skin is the body’s largest organ, Cheng says, so if it is not processing moisture correctly, that could indicate that some other health issue is going on.

“Different types of disease conditions result in different rates of water loss on our skin,” he says. “The skin will function differently based on those underlying conditions, which we will be able to flag and possibly characterize using the sensor.”

How wet is wet?

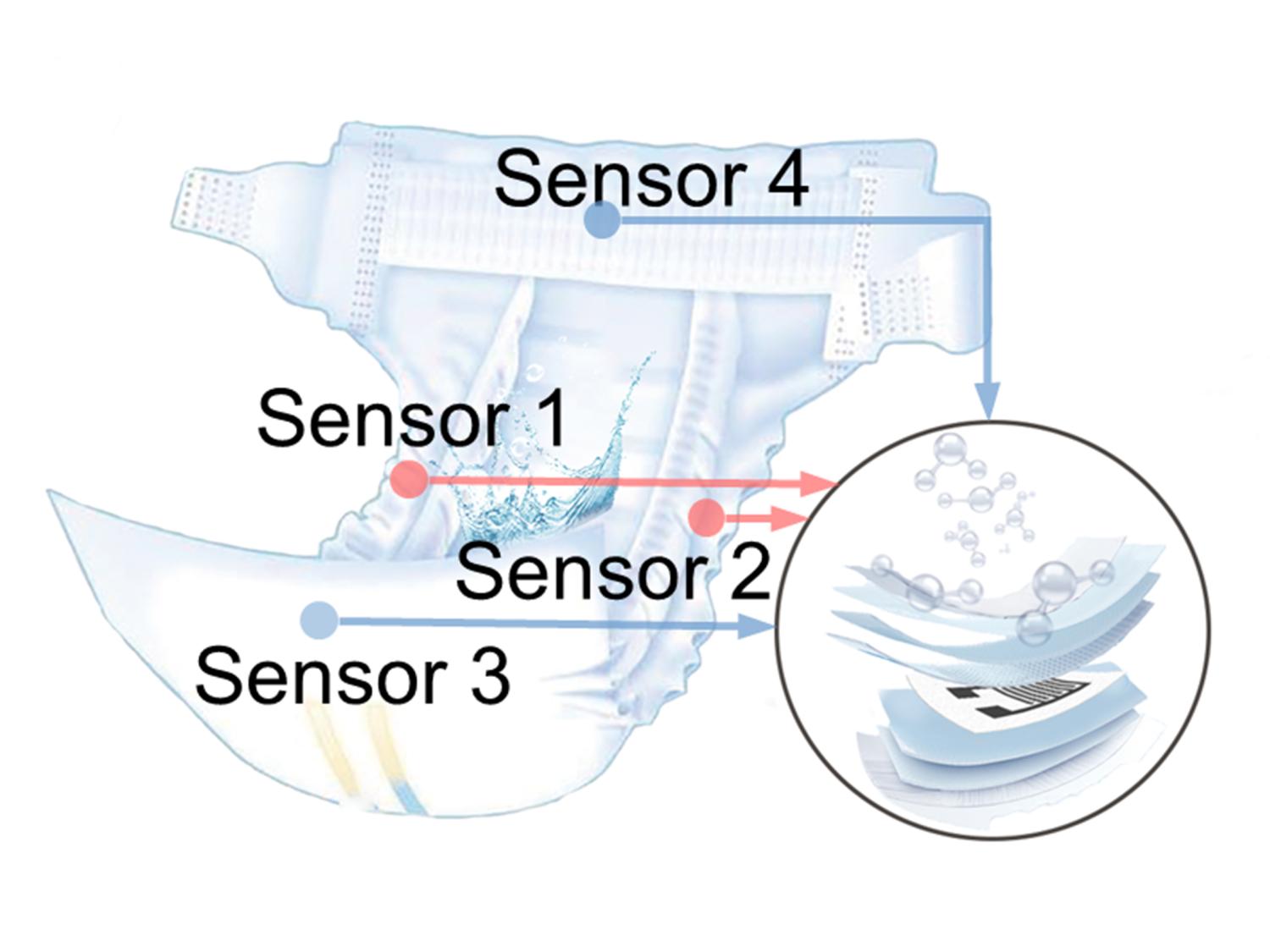

The team also integrated four humidity sensors between the absorbent layers of a diaper to create a “smart diaper,” capable of detecting wetness and alerting for a change.

“That application was actually born out of personal experience,” says Cheng, who is the father of two young children. “There’s no easy way to know how wet is wet, and that information could be really valuable for parents. The sensor can provide data in the short-term, to alert for diaper changes, but also in the long-term, to show patterns that can inform parents about the overall health of their child.”

The applications of the humidity sensor go beyond “smart diapers” and monitoring for respiration and perspiration, Cheng explains. The team also deployed the sensor as a noncontact switch, which could sense the humidity changes in the air from the presence of a finger without the finger touching the sensor. The team used the noncontact switch to operate a small-scale elevator, play a keyboard and light up an LED array.

“The atoms on the finger don’t need to touch the button, they only need to be near the surface to diffuse the water molecules and trigger the signal,” Cheng says. “When we think about what we learned from the pandemic about the need to limit the body’s contact with shared surfaces, a sensor like this could be an important tool to stop potential contamination.”

Additional coauthors are from Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin Tianzhong Yimai Technology Development Co. Ltd., and Penn State.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and Penn State funded the work.

Source: Penn State