A new wearable health sensor can reliably measure levels of important biochemicals in sweat during physical exercise.

The 3D-printed monitor could someday provide a simple and non-invasive way to track health conditions and diagnose common diseases, such as diabetes, gout, kidney disease, or heart disease.

As reported in the journal ACS Sensors, the researchers were able to accurately monitor the levels of volunteers’ glucose, lactate, and uric acid as well as the rate of their sweating during exercise.

“Diabetes is a major problem worldwide,” says Chuchu Chen, a PhD student at Washington State University and first author of the paper. “I think 3D printing can make a difference to the health care fields, and I wanted to see if we can combine 3D printing with disease detection methods to create a device like this.”

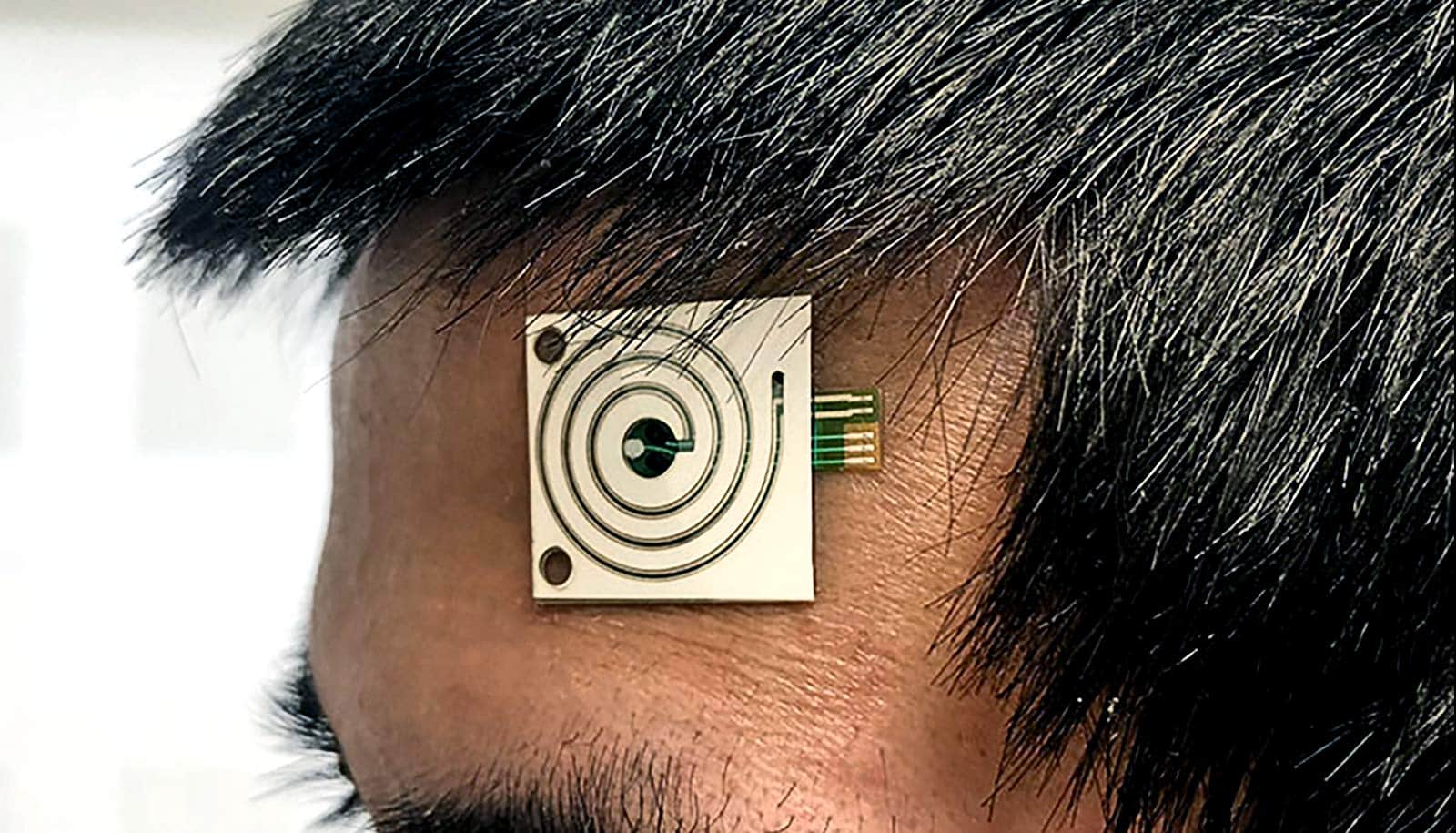

For their proof-of-concept health monitor, the researchers used 3D printing to make the health monitors in a unique, one-step manufacturing process. The researchers used a single-atom catalyst and enzymatic reactions to enhance the signal and measure low levels of the biomarkers. Three biosensors on the monitor change color to indicate the specific biochemical levels.

Sweat contains many important metabolites that can indicate health conditions, but, unlike blood sampling, it’s non-invasive. Levels of uric acid in sweat can indicate the risk of developing gout, kidney disease, or heart disease. Glucose levels are used to monitor diabetes, and lactate levels can indicate exercise intensity.

“Sweat rate is also an important parameter and physiological indicator for people’s health,” says Kaiyan Qiu, assistant professor in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering.

But the amount of these chemicals in sweat is tiny and can be hard to measure, the researchers note. While other sweat sensors have been developed, they are complex and need specialized equipment and expertise to fabricate. The sensors also have to be flexible and stretchable.

“It’s novel to use single-atom catalysts to enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of the health monitor,” says Annie Du, research professor in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering. Qiu and Du led the study.

The new health monitor is made of very tiny channels to measure the sweat rate and biomarkers’ concentration. As they’re being fabricated via 3D printing, the micro-channels don’t require any supporting structure, which can cause contamination problems as they’re removed, Qiu says.

“We need to measure the tiny concentrations of biomarkers, so we don’t want these supporting materials to be present or to have to remove them,” he says. “That’s why we’re using a unique method to print the self-supporting microfluidic channels.”

When the researchers compared the monitors on volunteers’ arms to lab results, they found that their monitor was accurately and reliably measuring the concentration of the chemicals as well as the sweating rate.

While the researchers initially chose three biomarkers to measure, they can add more, and the biomarkers can be customized. The monitors were also comfortable for volunteers to wear.

The researchers are now working to further improve the device design and validation. They are also hoping to commercialize the technology. The WSU Office of Commercialization has also filed a provisional patent application to protect the intellectual property associated with this technology.

The National Science Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work.

Source: Washington State