A wireless, wearable monitor built with stretchable electronics could allow comfortable, long-term health monitoring, researchers report.

The monitor works for adults, babies, and small children without concern for skin injury or allergic reactions conventional adhesive sensors with conductive gels cause.

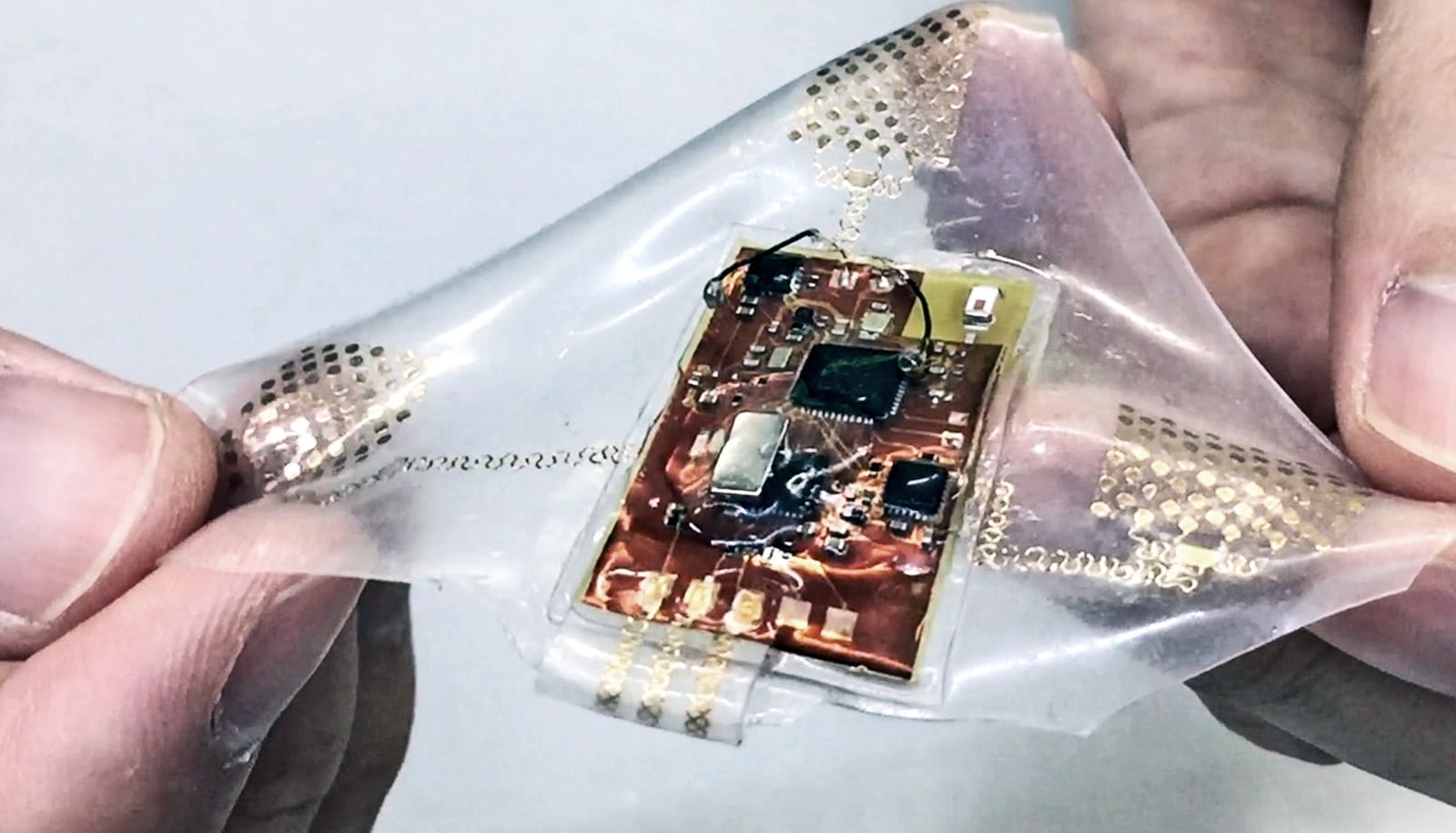

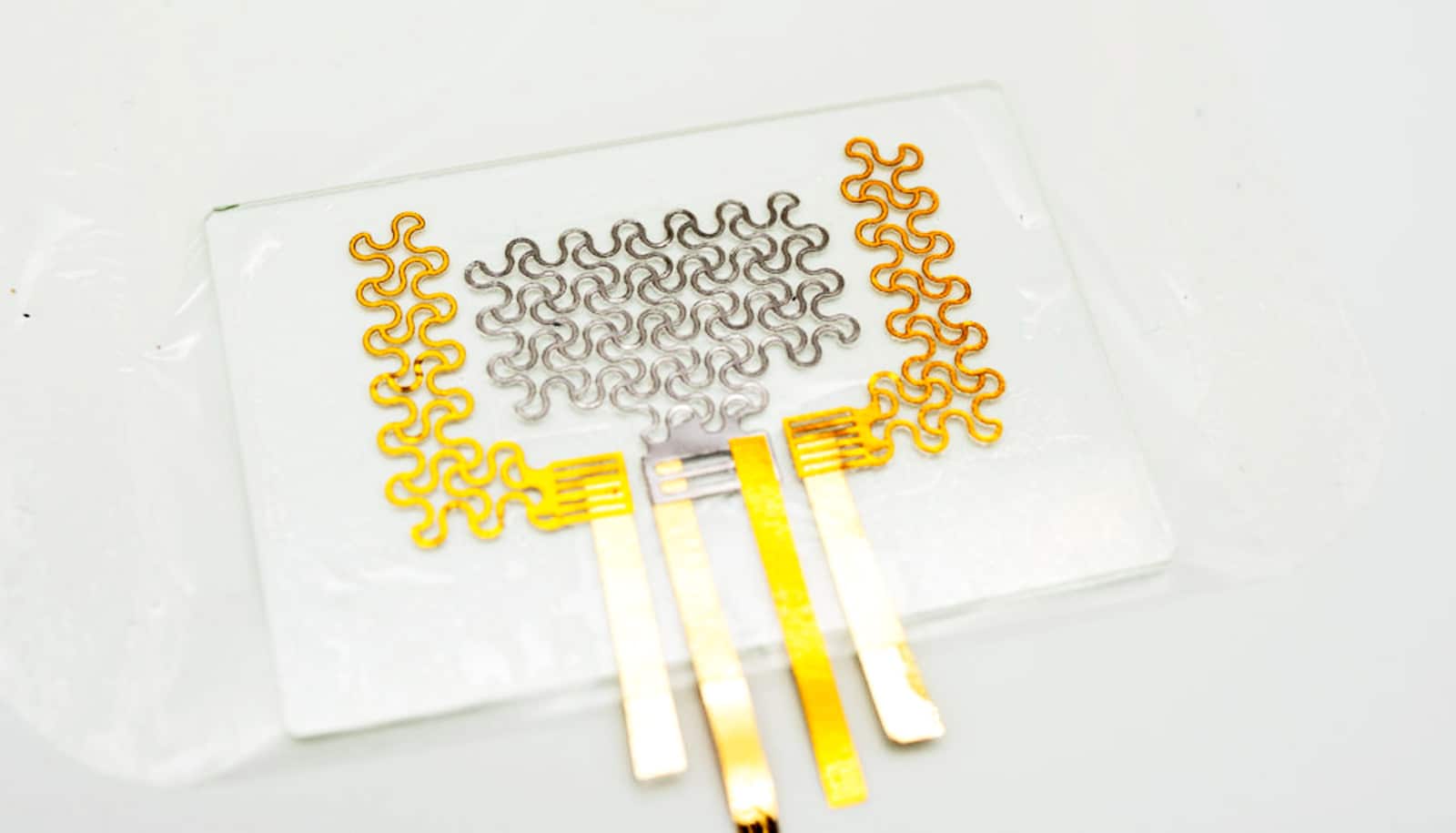

The soft and conformable monitor can broadcast electrocardiogram (ECG), heart rate, respiratory rate, and motion activity data as much as 15 meters (about 49 feet) to a portable recording device such as a smartphone or tablet computer. The researchers mounted the electronics on a stretchable substrate and connected them to gold, skin-like electrodes through printed connectors that can stretch with the medical film. They’ve studied the monitor on both animal models and humans.

Monitoring on the move

“This health monitor has a key advantage for young children who are always moving, since the soft conformal device can accommodate that activity with a gentle integration onto the skin,” says Woon-Hong Yeo, an assistant professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and biomedical engineering department at Georgia Institute of Technology. “This is designed to meet the electronic health monitoring needs of people whose sensitive skin may be harmed by conventional monitors.”

Because the device conforms to the skin, it avoids signal issues that the motion of the typical metal-gel electrodes across the skin can create. The device can even obtain accurate signals from a person who is walking, running, or climbing stairs.

“When you put a conventional electrode on the chest, movement from sitting up or walking creates motion artifacts that are challenging to separate from the signals you want to measure,” he says. “Because our device is soft and conformal, it moves with the skin and provides information that cannot be seen with the motion artifacts of conventional sensors.”

Catching issues early

Continuous evaluation with a wireless health monitor could improve the assessment of children and help clinicians identify trends earlier, potentially facilitating intervention before a condition progresses, says Kevin Maher, a pediatric cardiologist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

“The generation of continuous data from the respiratory and cardiovascular systems could allow for the application of advanced diagnostics to detect changes in clinical status, response to therapies, and implementation of early intervention,” Maher says. “A device to literally follow every breath a child takes could allow for early recognition and intervention prior to a more severe presentation of a disease.”

“The membrane is waterproof, so an adult could take a shower while wearing it. After use, the electronic components can be recycled.”

In the home, a wearable monitor might detect changes that might not otherwise be apparent, he says. In clinical settings, the wireless device could allow children to feel less “tethered” to equipment. “I see this device as a significant change in pediatric health care and am excited to partner with Georgia Tech on the project,” Maher adds.

The monitor uses three gold electrodes in the film that also contains the electronic processing equipment. The entire health monitor is just three inches in diameter, and a more advanced version under development will be half that size. A small rechargeable battery powers the wireless monitor currently, but future versions may replace the battery with an external radio-frequency charging system.

Yeo and his collaborators, including first author and postdoctoral fellow Yun-Soung Kim, are focusing on pediatric applications because of the need for ambulatory monitoring in children. However, they envision that the health monitor could also be used for other patient groups, including older adults who may also have sensitive skin. For adults, there would be additional advantages.

“The monitor could be worn for multiple days, perhaps for as long as two weeks,” Yeo says. “The membrane is waterproof, so an adult could take a shower while wearing it. After use, the electronic components can be recycled.”

2 versions of the wearable health monitor

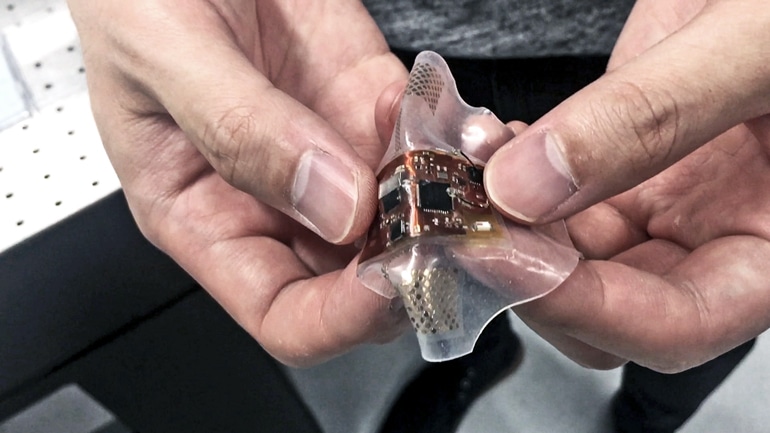

Researchers have developed two versions of the monitor. One is based on medical tape and designed for short-term use in a hospital or other care facility, while the other uses a soft elastomer medical film approved for use in wound care. The latter can remain on the skin longer.

“The devices are completely dry and do not require a gel to pick up signals from the skin,” Yeo explains. “There is nothing between the skin and the ultrathin sensor, so it is comfortable to wear.”

Because the monitor can be worn for long periods of time, it can provide a long-term record of ECG data helpful to understanding potential heart problems. “We use deep learning to monitor the signals while comparing them to data from a larger group of patients,” Yeo says. “If an abnormality is detected, it can be reported wirelessly through a smartphone or other connected device.”

Fabrication of the monitor’s circuitry uses thin-film, mesh-like patterns of copper that can flex with the soft substrate. The chips are the only parts that are not flexible, but they are mounted on the strain-isolated soft substrate instead of a traditional plastic circuit board.

What’s next?

As next steps, Yeo plans to reduce the size of the device and add features to measure other health-related parameters such as temperature, blood oxygen, and blood pressure. A major milestone would be a clinical trial to evaluate performance against conventional health monitors.

For Yeo, who specializes in nano- and micro-engineering, the prospect of seeing the device in clinical trials—and ultimately in children’s hospitals—is a powerful incentive.

“It will be a dream come true for me to see something we have developed be helpful to someone who is suffering,” he says. “We all want to see developments in science and engineering translated into improved patient care.”

Researchers detail the monitor in the journal Advanced Science.

Additional coauthors are from Georgia Tech, Wichita State University, Emory University, and the Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine in Korea. Support for the research came from the Imlay Innovation Fund at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, NextFlex (Flexible Hybrid Electronics Manufacturing Institute), and a seed grant from the Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology at Georgia Tech.

Source: Georgia Tech