A new electronic sensor can monitor water quality in homes or cities, informing residents or officials of the presence of lead in water within nine days—all for around $20.

The Flint water crisis showed the nation that old water systems believed to have been stable for decades can suddenly expose thousands of people to a neurotoxin if a change in water quality corrodes lead piping.

In addition, standard water sample tests require users to run their water for several minutes, missing any lead that leaches into the water from the home’s own pipes.

“I hope it will have some impact because it is scary to think about having lead in your water…”

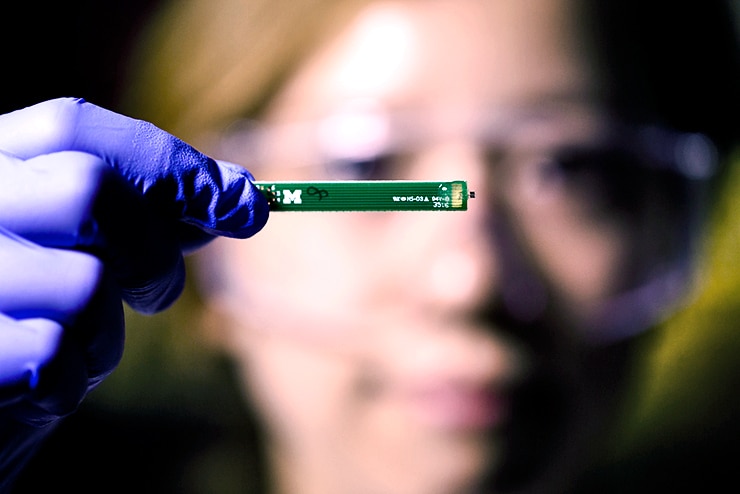

Mark Burns, a chemical engineering professor at the University of Michigan, and his colleagues set out to develop an inexpensive sensor that could be placed at key points in city water systems as well as at the taps in homes.

“I hope it will have some impact because it is scary to think about having lead in your water,” Burns says.

The trick is separating lead from all the other metals that might be present in water, most of them only hazardous in very high doses.

“Since iron is the most common metal in water and is basically harmless (besides having a bad odor), we see it as interfering with our sensor,” says Wen-Chi Lin, a recent doctoral graduate in chemical engineering.

So, she designed a sensor that could differentiate between lead and other metals like iron. It relies on two pairs of electrodes. The positive electrode and its neutral neighbor set up an electron-poor environment, while the negative electrode and its neutral neighbor create an electron-rich environment.

The negative electrode offers electrons to positive ions, capturing most metals. The metals are already oxidized in water, meaning they’ve given up some of their electrons, so they prefer an opportunity to get electrons back.

However, lead is attracted to the positive side of the electrode set—it is the only contaminant metal that readily loses more electrons and oxidizes further.

Lin tested the sensors in a variety of environments: simulated tap water and water from an actual tap, spiked with metals or not. As lead builds up on the positive electrode, it eventually reaches the neutral electrode, closing the circuit and generating a voltage. Above a one-volt signal, the system registers a hit.

Mom’s exposure to toxic chemicals shows up in newborn

It’s a similar story on the negative electrode, picking up high concentrations of iron, zinc, and copper, which can also become health concerns. The sensor can differentiate between a lead problem and a problem with one of these other metals.

“There could be an app that would monitor all the taps, and it could just send you an email message when it detected an event,” Burns says.

Lin was especially conscious of false positives—a detection means that the electrode is out of commission for good (but not the whole sensor), and it could cause an unnecessary scare for a family or official.

The one potential for a false lead alert is if the copper concentration is too high. Copper is so good at grabbing extra electrons that it can build up on the neutral electrode next to the positive electrode. But copper only creates a voltage at high concentrations, approaching its Environmental Protection Agency action limit of 1,300 parts per billion.

Lead, in contrast, shows up at 15 parts per billion—its EPA action limit—after about a week. This level of exposure isn’t thought to elevate blood levels in adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control. A larger concentration of lead, 150 parts per billion, was picked up after just one or two days, depending on the water chemistry.

Lin believes that with optimization, the positive electrode could be better yet at attracting lead but not copper.

Do cars and clothes bring lead exposure home?

The study appears in Analytical Chemistry.

The University of Michigan funded the work through the Barbour Scholarship, Rackham Predoctoral Fellowship, and the T.C. Chang Endowed Professorship.

Source: University of Michigan