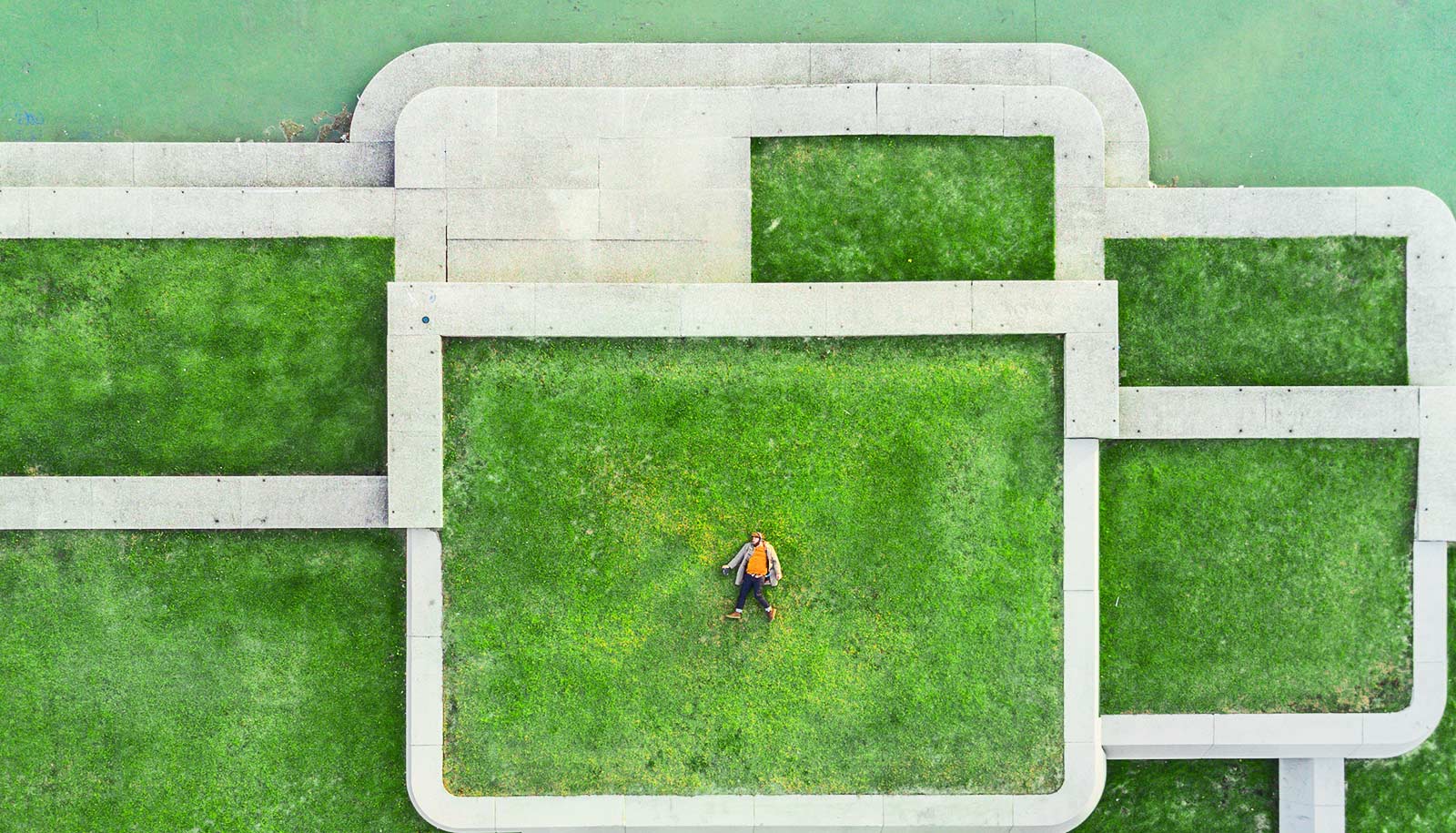

Investing in walking and biking, coupled with proposed emissions caps, could save hundreds of lives and billions of dollars each year in the Northeast United States.

Infrastructure investments to promote bicycling and walking—proposed by the Transportation and Climate Initiative (TCI), a regional collaboration of 12 northeastern states and Washington, DC—could save as many as 770 lives and $7.6 billion annually. Those findings appear in the Journal of Urban Health.

The analysis shows that the economic benefit of lives saved from increased walking and cycling far exceeds the estimated annual investment it would cost to promote such infrastructure, without even considering the added benefits of reducing air pollution and increasing access to climate-friendly transportation modes.

In December 2020, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and DC became the first jurisdictions to formally join the TCI. “Our study suggests that if all the [northeastern] states joined TCI and collectively invested at least $100 million in active mobility infrastructure and public transit, the program could save hundreds of lives per year from increased physical activity,” says the study’s lead author Matthew Raifman, a doctoral student in environmental health at the Boston University School of Public Health.

The TCI, which is currently under development, seeks to implement a “cap-and-invest” program to reduce transportation sector emissions across the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, including substantial investment in cycling and pedestrian infrastructure, as well as other sustainable transportation strategies like electric vehicle charging stations and improved public transit. Cap-and-invest programs limit the emissions allowed from an industry or economy, and those allowances get lower over time, resulting in cleaner air and improved public health. They require air-pollution-producing entities to purchase emissions allowances, generating investment funds that can be used to offset emissions through development of greener, cleaner infrastructure.

“[Our] findings demonstrate how investments in climate-friendly transportation options like biking and walking can reap huge health and economic benefits at the local level,” says Patrick Kinney, the study’s senior author and professor for the improvement of urban health.

Kinney, Raifman, and collaborators used an investment scenario model and the World Health Organization (WHO) Health Economic Assessment Tool methodology to estimate how many lives would be saved in each of the 378 counties in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions thanks to increased physical activity (walking, running, and cycling) and accounting for the potential decrease in fatalities from car accidents.

As part of their analysis, the team analyzed nine proposed TCI scenarios that differ in their greenhouse gas emission caps, as well as how the proceeds from the program would be invested across a range of transportation options.

The scenario with the largest health benefits assumed a 25% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, and an influx of $632 million worth of cap-and-invest proceeds in cycling and pedestrian infrastructure across the 12 states and DC. The researchers estimate that this scenario could save 770 lives across the regions due to reduced cardiovascular mortality, accounting for changes in pedestrian accident fatality rates. The monetary value of the reduced health risk is $7.6 billion per year.

Health benefits across the other scenarios roughly scaled down in sync with the degree of investment in pedestrian and cycling infrastructure. For example, a more modest scenario would invest $130 million in cycling and pedestrian infrastructure, saving around 200 lives regionally due to increased physical activity—a monetary value of $1.8 billion. The states with the largest estimated health benefits from active mobility under all policy scenarios are the populous states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland.

“Investments in active mobility would not only increase physical activity but would also reduce air pollution levels and start to address the climate crisis,” says Jonathan Levy, study coauthor and professor and chair of environmental health. “This study reinforces the importance of considering near-term health benefits when developing climate policy.”

The authors also urge that investment in walking and cycling infrastructure can be thoughtfully designed to increase access to greener, healthier modes of transportation in the communities most vulnerable to the effects of air pollution and climate change.

“Given the legacy of inequitable investment in infrastructure in the United States, the opportunity exists to address racial disparities in access to sidewalks and cycling infrastructure through equity-focused project siting,” Raifman says.

The study is part of the Transportation, Equity, Climate and Health (TRECH) Project, based at the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Harvard Chan C-CHANGE). TRECH is made possible in part by a grant from the Barr Foundation to Harvard Chan C-CHANGE. This research also had support from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Source: Boston University