New research reveals a new trigger for Venus flytraps, which catch spiders and insects by snapping their leaves shut.

This happens when unsuspecting prey touch highly sensitive trigger hairs twice within 30 seconds. The new study shows that a single slow touch also triggers trap closure—probably to catch slow-moving larvae and snails.

The Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) is perhaps the most well-known carnivorous plant. Its distinct leaves have three highly sensitive trigger hairs on each lobe. These hairs react to even the slightest touches—e.g. when a fly crawls along the leaf—by sending out an electrical signal, which quickly spreads across the entire leaf. If two signals are triggered in a short time, the trap snaps within milliseconds.

“Contrary to popular belief, slowly touching a trigger hair only once can also cause two signals and thus lead to the snapping of the trap,” says co-last author Ueli Grossniklaus, director of the department of plant and microbial biology at the University of Zurich.

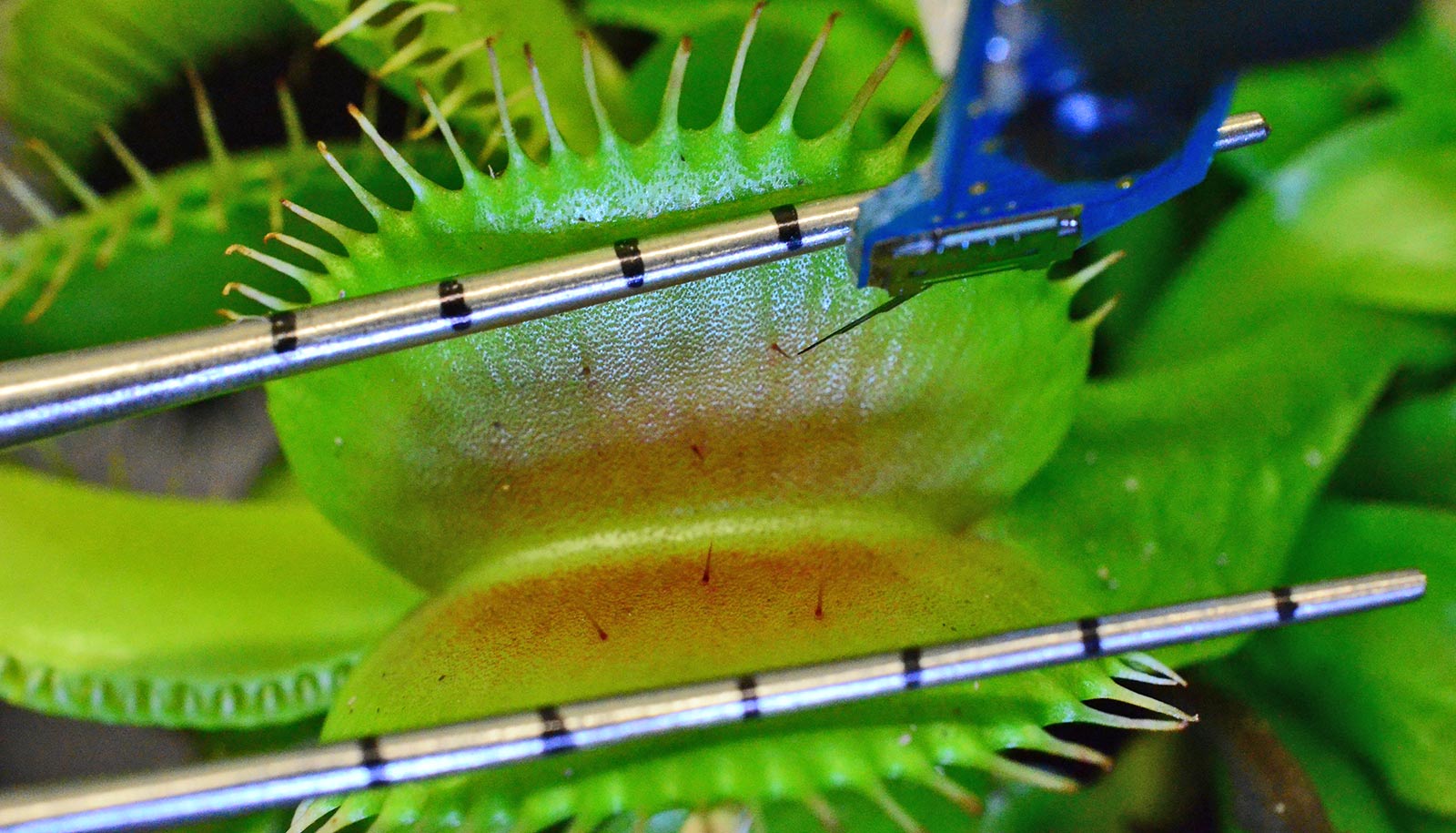

First, the researchers determined the forces needed to trigger the plant’s trapping mechanism. They did this by using highly sensitive sensors and high-precision microrobotic systems that the team of co-last author Bradley J. Nelson developed at ETH Zurich’s Institute of Robotics and Intelligent Systems. This enabled the scientists to deflect the trigger hairs to a precise angle at a pre-defined speed in order to measure the relevant forces.

From the collected data, the researchers at the ETH Institute for Building Materials developed a mathematical model to determine the range of angular deflection and velocity thresholds that activate the snapping mechanism.

“Interestingly, the model showed that at slower angular velocities one touch resulted in two electrical signals, such that the trap ought to snap,” says Grossniklaus. The researchers were subsequently able to confirm the model’s prediction in experiments.

When open, the lobes of the Venus flytrap’s leaves are bent outwards and under strain—like a taut spring. The trigger signal leads to a minute change in the leaves’ curvature, which makes the trap snap instantaneously. The electrical signals are generated by ion channels in the cell membrane, which transport atoms out of and into the cell.

“We think that the ion channels stay open for as long as the membrane is mechanically stretched. If the deflection occurs slowly, the flow of ions is enough to trigger several signals, which causes the trap to close,” explains co-first author Hannes Vogler, plant biologist at the University of Zurich.

The findings appear in the journal PLOS Biology.

Source: University of Zurich