A new study finds that kimchi made without fish products has the same type of bacteria as the more traditional recipe. That finding suggests that vegan versions would have the same probiotic effects.

Along with other fermented foods like yogurt and kombucha, kimchi is surging in popularity as a probiotic food—one that contains the same kinds of healthy bacteria found in the human gut.

A traditional Korean side dish, kimchi consists mainly of fermented cabbage, radish, and other vegetables. But it normally contains fish sauce, fish paste, or other seafood. That takes it off the menu for people who don’t eat fish, including vegans (who don’t eat anything containing animal products). But in order to appeal to vegan consumers, some producers have begun making a vegan alternative to traditional kimchi.

“In vegan kimchi, producers swap in things like miso, which is a fermented soybean paste, in place of the seafood components,” says Michelle Zabat, an undergraduate at Brown University and lead author of the study in Food Microbiology. “We wanted to know what the effects of making that swap might be in terms of the microbial community that’s produced during fermentation.”

Bacteria, before and after

Working in the lab of Peter Belenky, an assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology, Zabat worked with Chi Kitchen, a Pawtucket, Rhode Island-based company that makes both traditional and vegan kimchi.

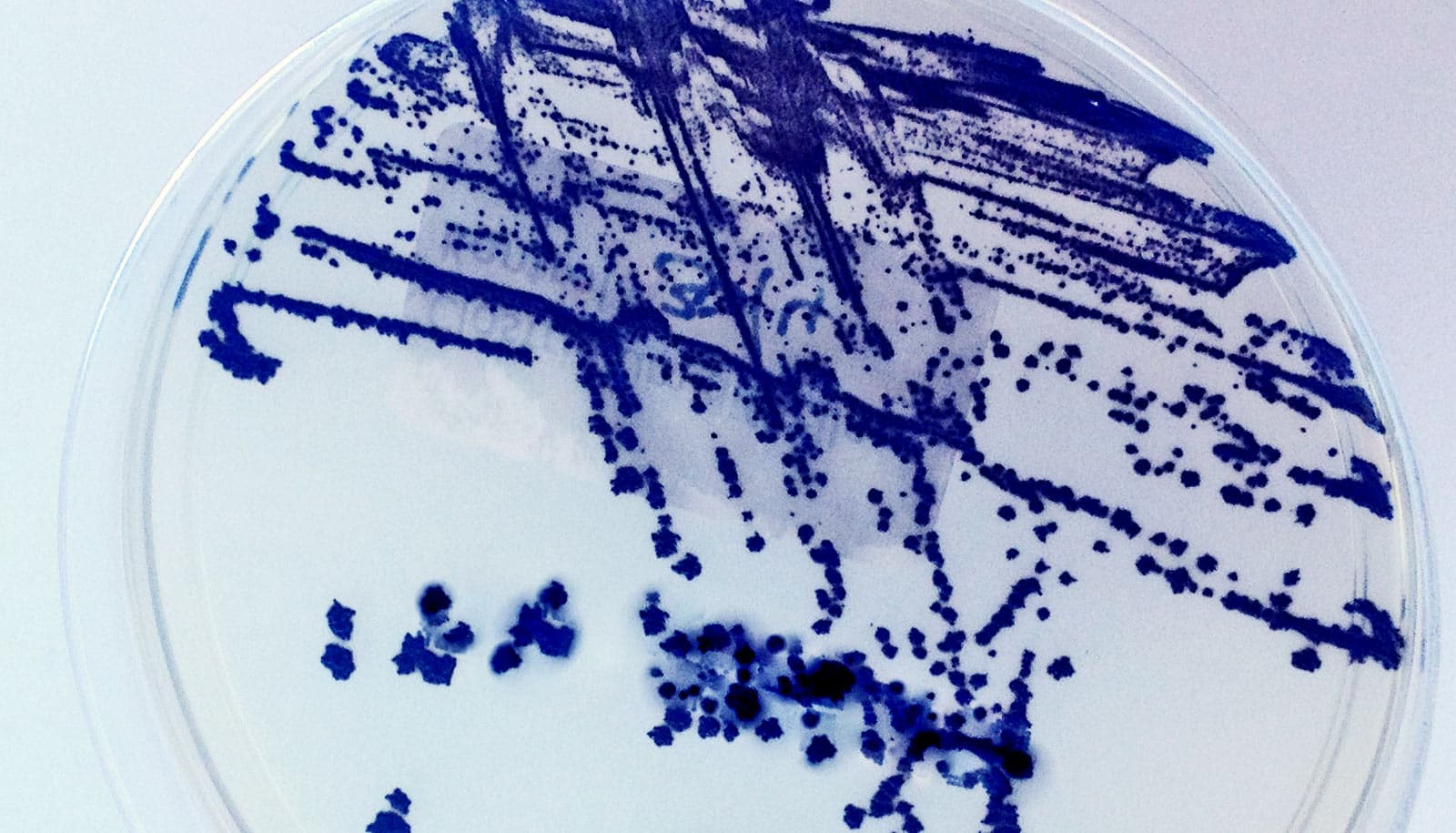

The researchers took bacterial samples from the starting ingredients of both kinds of kimchi, as well as samples during the fermentation process and from the final products. The team took additional environmental samples from the factory, including from production tables, sinks, and floors. The researchers then used high-throughput DNA sequencing to identify the types of bacteria present.

The study shows that the vegan and traditional kimchi ingredients had very different microbial communities to start, but over the course of fermentation the communities quickly became more similar. By the time fermentation was complete, the two communities were nearly identical. Lactobacillus and leuconostoc, genuses well known to thrive in fermented cabbage dominated both. Those bacteria were present only in small amounts in the starting ingredients for both products, the researchers found, yet were the only bacteria to survive the fermentation environment.

That’s not exactly what the researchers expected to see.

“Miso has a lot of live bacteria in it at the start,” Belenky says. “The fact that those bacteria were lost almost immediately during the fermentation was surprising. We thought they’d carry over to the kimchi, but they didn’t.”

That’s likely because bacteria found in the miso thrive in extremely salty environments, and the kimchi isn’t quite salty enough for them. “If we made really salty kimchi,” Belenky says, “we might see them.”

Consumers are ahead of the science

The study looked at only one brand of kimchi, and it’s not a sure thing that the findings will to the same for other brands. In fact, researchers point out that the microbial community that dominated the kimchi they tested closely matched the community in samples taken from the production facility. It’s not clear from this study whether those bacteria in the environment came from the kimchi or the other way around. It’s possible, the researchers say, that the facility provided a “starter culture” that influences the eventual microbial community in the kimchi.

Can bacteria in yogurt calm your anxiety?

Either way, the findings show that it is indeed possible to make a vegan kimchi that’s remarkably similar in terms of microbes to for kimchi that’s made with more traditional ingredients. The jury is still out on whether consuming probiotics actually makes meaningful changes to the gut microbiome or has any overall health benefits, the researchers say. But to the extent that consumers want products with probiotics and producers want to cater to dietary restrictions, vegan kimchi appears to fit the bill.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Karen T. Romer Undergraduate Teaching and Research Award from Brown University supported the work.

Source: Brown University