A vaccine administered directly to the bladder clears the bacteria that cause urinary tract infections, a new study with mice shows.

Anyone who has ever developed a urinary tract infection (UTI) knows that it can be painful, pesky, and persistent. UTIs have a high recurrence rate and primarily afflict women—as many as 50% of women will experience at least one UTI during their lifetime.

As reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers say they think a new vaccination strategy could re-program the body to successfully fight off the bacteria that cause urinary tract infections.

“Although several vaccines against UTIs have been investigated in clinical trials, they have so far had limited success,” says senior author Soman Abraham, professor of pathology, immunology, and molecular genetics and microbiology in the Duke University School of Medicine.

“There are currently no effective UTI vaccines available for use in the US in spite of the high prevalence of bladder infections,” Abraham says. “Our study describes the potential for a highly effective bladder vaccine that can not only eradicate residual bladder bacteria, but also prevent future infections.”

The strategy, which the team proved effective in mouse models, involves re-programming an inadequate immune response that the team identified last year.

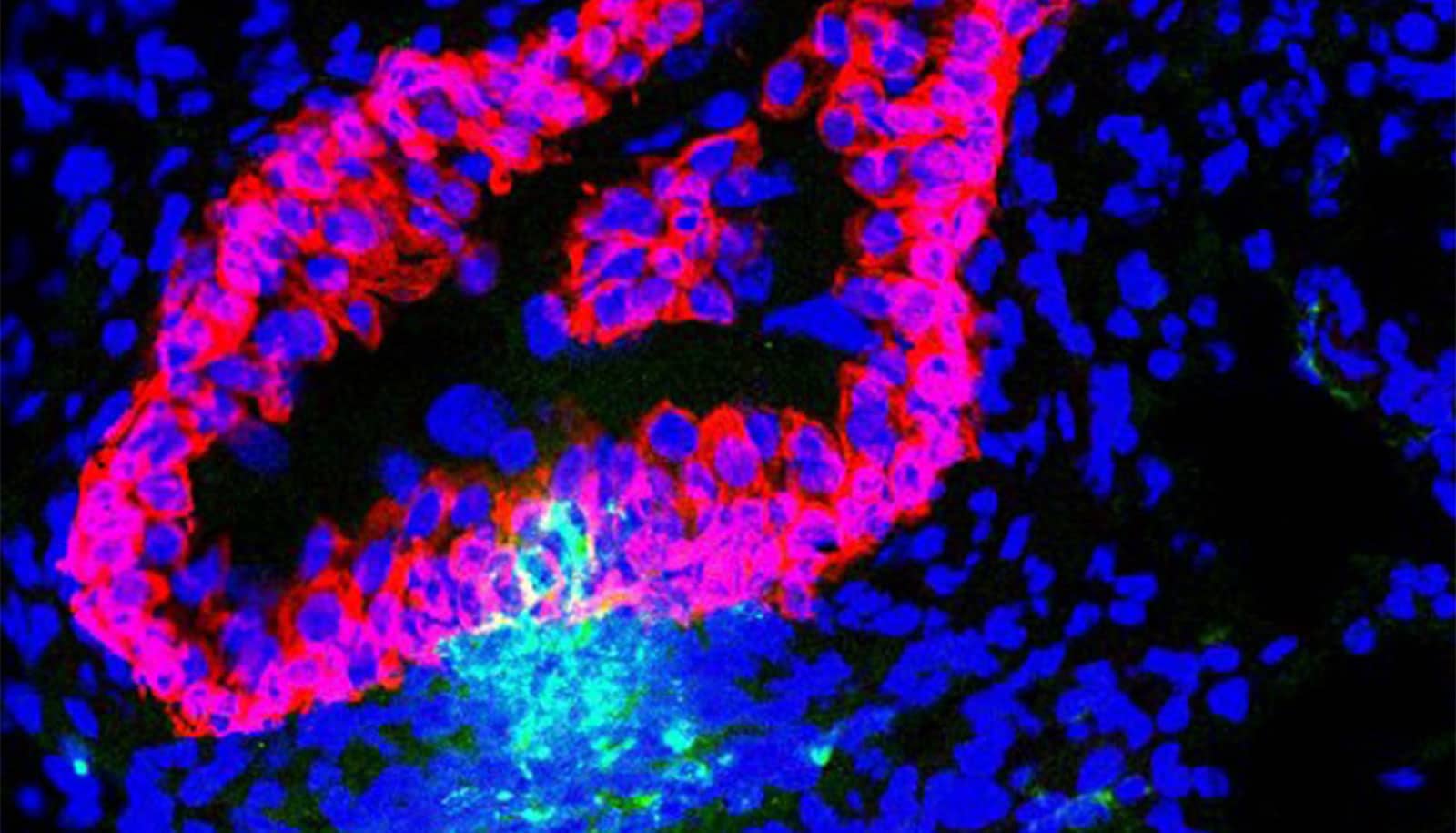

They observed that when mouse bladders get infected with E. coli bacteria, the immune system dispatches repair cells to heal the damaged tissue, while launching very few warrior cells to fight off the attacker. This causes bacteria to never fully clear, living on in the bladder to attack again.

“The new vaccine strategy attempts to ‘teach’ the bladder to more effectively fight off the attacking bacteria,” says lead author Jianxuan Wu, who recently earned his doctorate from the immunology department.

“By administering the vaccine directly into the bladder where the residual bacteria harbor, the highly effective vaccine antigen, in combination with an adjuvant known to boost the recruitment of bacterial clearing cells, performed better than traditional intramuscular vaccination.”

The bladder-immunized mice effectively fought off infecting E. coli and eliminated all residual bladder bacteria, suggesting the site of administration could be an important consideration in determining the effectiveness of a vaccine, the researchers report.

“We are encouraged by these findings, and since the individual components of the vaccine have previously been shown to be safe for human use, undertaking clinical studies to validate these findings could be done relatively quickly,” Abraham says.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work.

Source: Duke University