A new report shows that the United States has the capacity to make the nation’s most essential and critical drugs—yet it’s mostly sitting idle.

President Joe Biden signed an executive order September 12 to launch a National Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Initiative, noting the United States relies too heavily on foreign materials and foreign bioproduction. Offshoring of critical industries threatens the nation’s ability to access materials such as important chemicals and active pharmaceutical ingredients.

Consider the prescriptions you or your loved ones need for high blood pressure, infections, or other ailments. Chances are, no manufacturing source exists in the United States for critical generic drugs or their active ingredients.

In fact, in 2021 the White House sounded the alarm about vulnerabilities in the pharmaceutical supply chain. “The disappearance of domestic production of essential antibiotics impairs our ability to counter threats ranging from pandemics to bio-terrorism,” a White House report proclaimed.

Insufficient US manufacturing capacity due to offshoring was largely to blame. But new research from Washington University in St. Louis’ Center for Analytics and Business Insights (CABI) at Olin Business School suggests otherwise.

The CABI report fills a crucial gap in available industry data.

“We addressed of a significant blind spot, which was the understanding of available capacity in the United States to build supply chain resiliency,” says Anthony Sardella, author of the CABI report, senior research adviser for CABI, and an adjunct lecturer at Olin Business School.

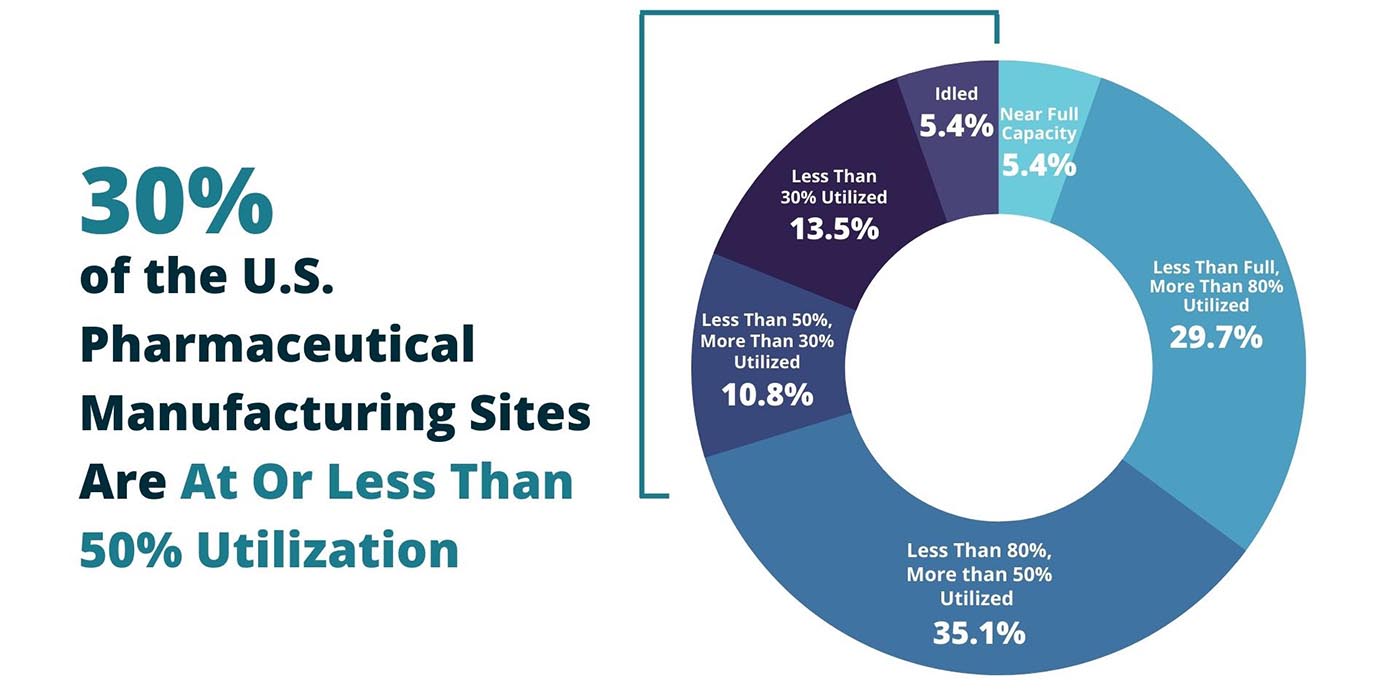

“Our results were quite surprising. Fifty percent of available capacity is not utilized,” he says. “The number was stunning.”

The Biden administration said September 14 that it will invest more $2 billion into biotech and biomanufacturing efforts.

Last year, the generic pharmaceutical industry made headlines when it announced the closure of several US manufacturing plants. Why? Factors include lower offshore operating costs and labor rates, intense pricing pressure, and steadily growing dependence on offshore sources for raw materials.

“How do we account for this incongruency?” Sardella asks. He and his team surveyed 37 US generic pharmaceutical manufacturing sites. They found the sites are producing at just half of their production capacity annually, with an aggregate excess capacity of nearly 50%. In fact, only two of the 37 manufacturing sites are producing at full capacity.

If the sites got up and running, nearly 30 billion additional doses of essential and critical medicines could be produced in the US without the expense and effort of building new manufacturing plants, shortening the time to make generic medicines available from domestic sources, the report finds.

In short, the report recommends the following:

- Repurpose idle sites to enable manufacturing to address shortages, increase supply-chain resiliency, and build supplies within 24-36 months.

- Continue current federal funding efforts for advanced manufacturing technologies to reduce production costs, create new workforce opportunities, and increase the economic sustainability of US drug manufacturing.

Sardella will present the paper’s results Tuesday, October 4, at the National Press Club in Washington to provide support for policy considerations and initiatives to strengthen US drug manufacturing sustainability.