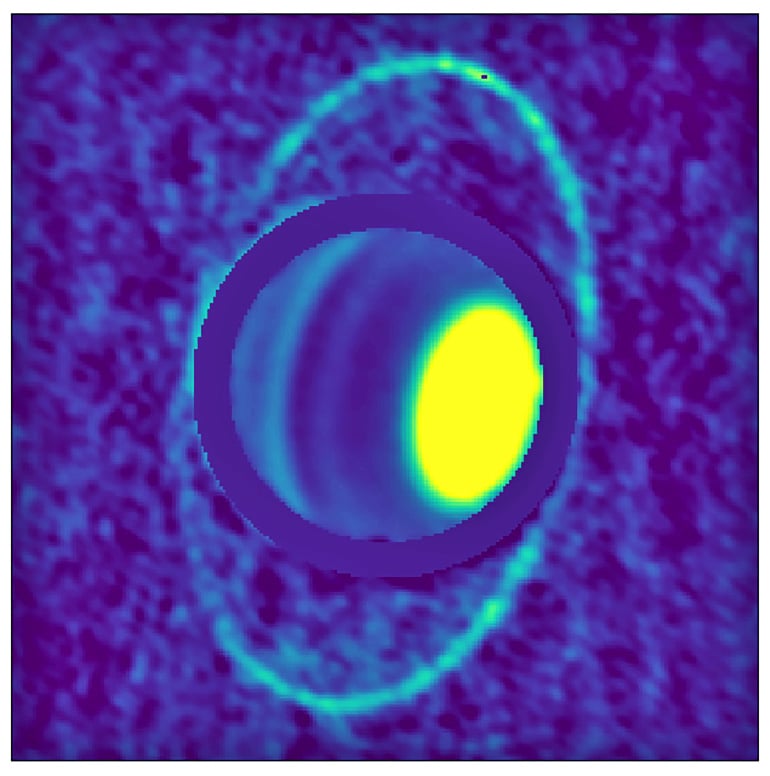

The rings of Uranus, while invisible to all but the largest telescopes, are surprisingly bright in new heat images of the planet taken by two large telescopes in the high deserts of Chile.

The thermal glow gives astronomers another window onto the rings, which have been seen only because they reflect a little light in the visible, or optical, range and in the near-infrared. Scientists first discovered the rings in 1977.

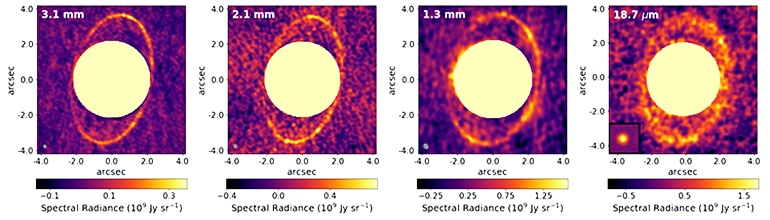

The new images taken by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Very Large Telescope (VLT) allowed the team for the first time to measure the temperature of the rings: a cool 77 Kelvin, or 77 degrees above absolute zero—the boiling temperature of liquid nitrogen and equivalent to 320 degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

The observations also confirm that Uranus’s brightest and densest ring, called the epsilon ring, differs from the other known ring systems within our solar system, in particular the spectacularly beautiful rings of Saturn.

Differences in rings around Saturn and Uranus

“Saturn’s mainly icy rings are broad, bright, and have a range of particle sizes, from micron-sized dust in the innermost D ring, to tens of meters in size in the main rings,” says Imke de Pater, a professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley. “The small end is missing in the main rings of Uranus; the brightest ring, epsilon, is composed of golf ball-sized and larger rocks.”

By comparison, Jupiter’s rings contain mostly small, micron-sized particles (a micron is a thousandth of a millimeter). Neptune’s rings are also mostly dust, and even Uranus has broad sheets of dust between its narrow main rings.

“We already know that the epsilon ring is a bit weird, because we don’t see the smaller stuff,” says graduate student Edward Molter. “Something has been sweeping the smaller stuff out, or it’s all glomming together. We just don’t know. This is a step toward understanding their composition and whether all of the rings came from the same source material, or are different for each ring.”

Rings could be former asteroids the planet’s gravity captured, remnants of moons that crashed into one another and shattered, the remains of moons torn apart when they got too close to Uranus, or debris remaining from the time of formation 4.5 billion years ago.

“The rings of Uranus are compositionally different from Saturn’s main ring, in the sense that in optical and infrared, the albedo is much lower: they are really dark, like charcoal,” Molter says. “They are also extremely narrow compared to the rings of Saturn. The widest, the epsilon ring, varies from 20 to 100 kilometers wide, whereas Saturn’s are 100’s or tens of thousands of kilometers wide.”

Scientists first noted the lack of dust-sized particles in Uranus’s main rings when Voyager 2 flew by the planet in 1986 and photographed them. The spacecraft was unable to measure the temperature of the rings, however.

To date, astronomers have counted a total of 13 rings around the planet, with some bands of dust between the rings. The rings differ in other ways from those of Saturn.

A clear picture

“It’s cool that we can even do this with the instruments we have,” he says. “I was just trying to image the planet as best I could and I saw the rings. It was amazing.”

Both the VLT and ALMA observations were designed to explore the temperature structure of Uranus’ atmosphere, with VLT probing shorter wavelengths than ALMA.

“We were astonished to see the rings jump out clearly when we reduced the data for the first time,” says Leigh Fletcher from the University of Leicester.

This presents an exciting opportunity for the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, which will be able provide vastly improved spectroscopic constraints on the Uranian rings in the coming decade.

The new data will appear in The Astronomical Journal.

Additional researchers from the University of Leicester contributed to the work. Funding for the research came from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Work at the University of Leicester was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program.

Source: UC Berkeley