New research may answer a long-standing question about how proteins act inside cells.

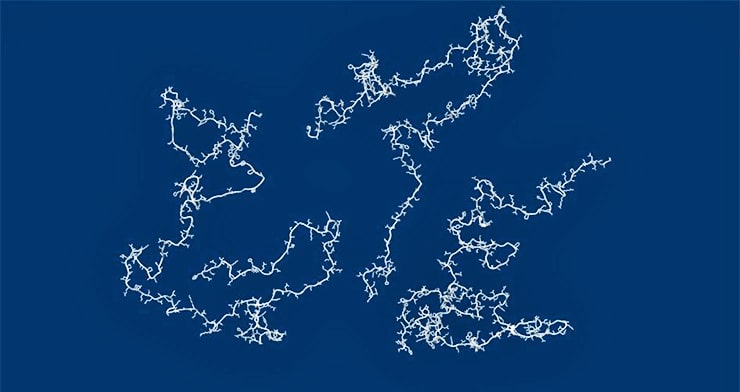

For many years, scientists thought that all proteins must fold into complicated shapes to fulfill their functions, looking like thousands of sets of custom-tailored locks and keys. But over the past two decades, scientists have begun to realize other proteins—including those involved in many essential cellular functions—remain fully or partially unfolded for parts of their lives.

Out of this realization has come a debate: how such proteins spend their time when floating in the cell. Since they’re not folded into their precise shapes, do they contract into balls, or remain expanded, like a rope?

Different methods have yielded different results. Scattering using X-rays suggested they remained expanded, but fluorescent methods observed the opposite behavior. The answer would affect how we envision the movement of a protein through its life—essential for understanding how proteins fold, what goes wrong during disorders and disease, and how to model their behavior.

“The results are very clear, but contradict the current consensus…”

Now, a team of researchers have used simulations and X-rays to tackle the question. They conclude that these proteins remain unfolded and expanded as they float loose in the cytoplasm of a cell.

“What we need to determine is how ‘sticky’ they are,” says coauthor Tobin Sosnick, chair of the biochemistry & molecular biology department at the University of Chicago, as well as director of the graduate program in biophysical sciences. “For survival, you want a protein to ‘stick’ only in the right conformation, and with the right other pieces or partners at the right times.” This stickiness is determined by the protein’s chemistry and physics.

Sosnick’s team came up with a way to analyze a single X-ray measurement to determine stickiness, finding that the proteins are generally much less sticky than expected. Their chemistry is set up to prefer to interact with water, rather than itself or other proteins.

Supercomputer peeks into cell to observe proteins

“The results are very clear, but contradict the current consensus,” Sosnick says. “It’s possible that proteins can avoid unwanted interactions by being expanded.” This reduces the chances of them sticking to other proteins by accident, causing dysfunction or disease.

The researchers report their work in the journal Science.

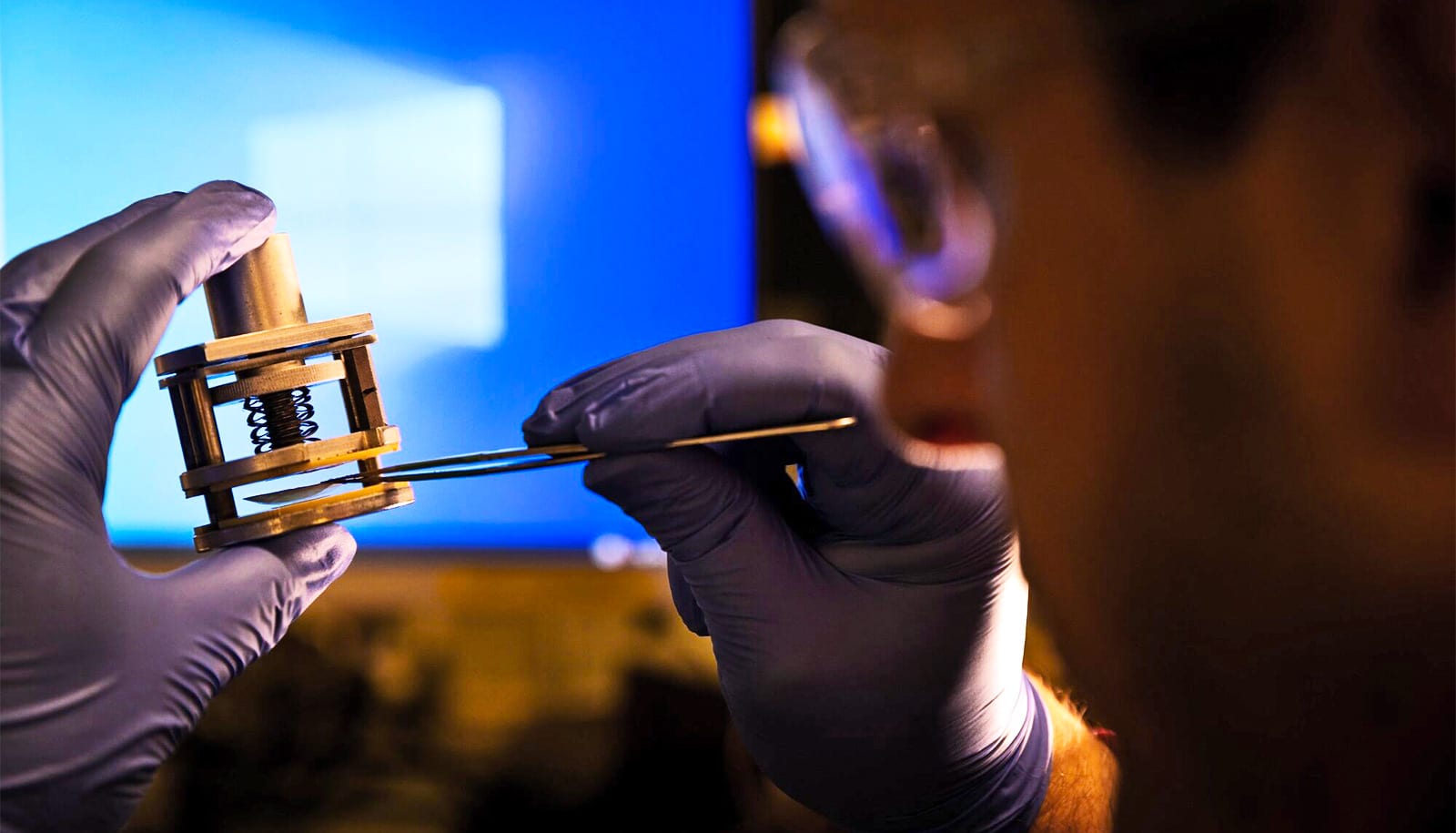

Additional researchers who contributed to the work are from the University of Chicago and the University of Notre Dame. The researchers conducted the X-rays measurements at the nearby Advanced Photon Source, a powerful synchrotron at Argonne National Laboratory.

The National Institutes for Health, the National Science Foundation, and the US Department of Energy for the Advanced Photon Source funded the research.

Source: University of Chicago