Ultra-bright galaxies in the early universe may be less common than scientists initially thought, according to new research.

Researchers used the Hubble Space Telescope to observe two galaxies thought to be so distant that we see them more than 13 billion years back in time when the universe was young.

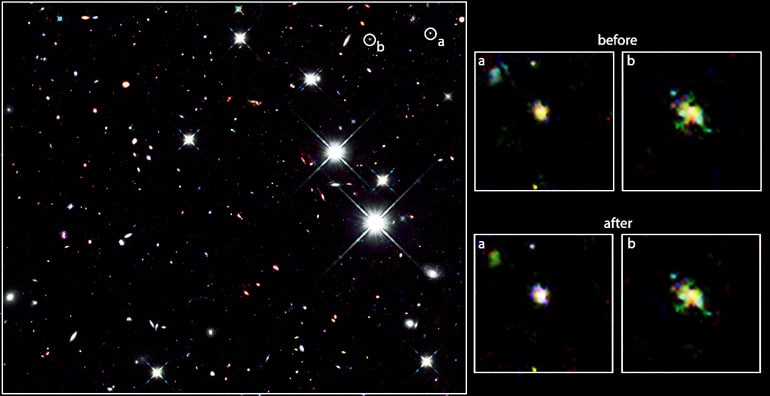

The Brightest of Reionizing Galaxies (BoRG) survey team found one galaxy was a bright source seen more than 13 billion years ago, as expected. But the other was an “impostor”—a relatively nearby galaxy mistaken for one very far away due to its red color.

The effect known as redshift gives distant galaxies distinct colors that can indicate how far away they are. But some relatively nearby galaxies have deceptively similar colors, lending some uncertainty to their estimated distance.

The researchers say this discovery—that the brightest known galaxy candidate in the early universe is essentially a fraud—has profound implications for models of how galaxies formed when the universe was in its infancy.

The BoRG project

BoRG is designed to find bright early galaxies. The BoRG project, which Michele Trenti, an associate professor from the University of Melbourne and the ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics, leads, exploits Hubble’s ability to use multiple cameras at once.

Trenti says that while another camera was in use, the BoRG team used the highly sensitive Wide Field Camera 3 to observe a random patch of sky for a few hours. He says repeating this more than 100 times built up a rich dataset that covers unrelated universe parts, maximizing the chances of landing a rare, bright, young galaxy.

“Looking really far away basically allows us to take baby pictures of galaxies…”

“Since Hubble primary time is so scarce and oversubscribed, the BoRG survey represents an ideal opportunity to carry out cutting-edge science at no extra cost,” Trenti says. “It is essentially doubling the productivity of an already amazing telescope.”

Researchers first observed the two galaxies in this study as part of the BoRG survey and reported the observations in a 2016 paper.

The latest study used Hubble to look again at those sources in order to take a more detailed measurement of the two galaxies’ colors, thus refining their estimated distances. One was from more than 13 billion years ago, when the universe was only five percent of its current age.

Young and bright

Astrophysicist Rachael Livermore, who led the research following up BoRG’s discovery, says this galaxy was incredibly bright compared to its peers.

“This makes it a perfect target for further study, so that we can really understand what’s going on inside galaxies way back in the early years of the universe,” Livermore says.

The second galaxy was thought to be the brightest galaxy discovered in the first 650 million years after the Big Bang, but turned out to be a fraud.

“Looking really far away basically allows us to take baby pictures of galaxies, so we can see how they started and then figure out how they grew into the types of galaxies we see today,” Livermore says.

‘Fuel tanks’ extend starburst phase of young galaxies

“Now that we have a better measurement of the colors, it now looks as though the brightest galaxy is actually relatively nearby—we see it only 9 billion years back in time, whereas it was previously thought to be 13 billion.”

These galaxies are a natural target for Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, which is due to launch in 2021. The new telescope is designed to find and characterize very early galaxies and the BoRG team hopes to use it for further research.

The latest study appears in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Support for the work came from the ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), a Research Centre of Excellence that the Australian Research Council (ARC), and six collaborating universities—the Australian National University, the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, Swinburne University of Technology, the University of Western Australia, and Curtin University—partially funded the study.

Source: University of Melbourne