While smaller dinosaurs needed speed, huge predators like Tyrannosaurus rex had bodies optimized for energy-efficient walking, according to a new study.

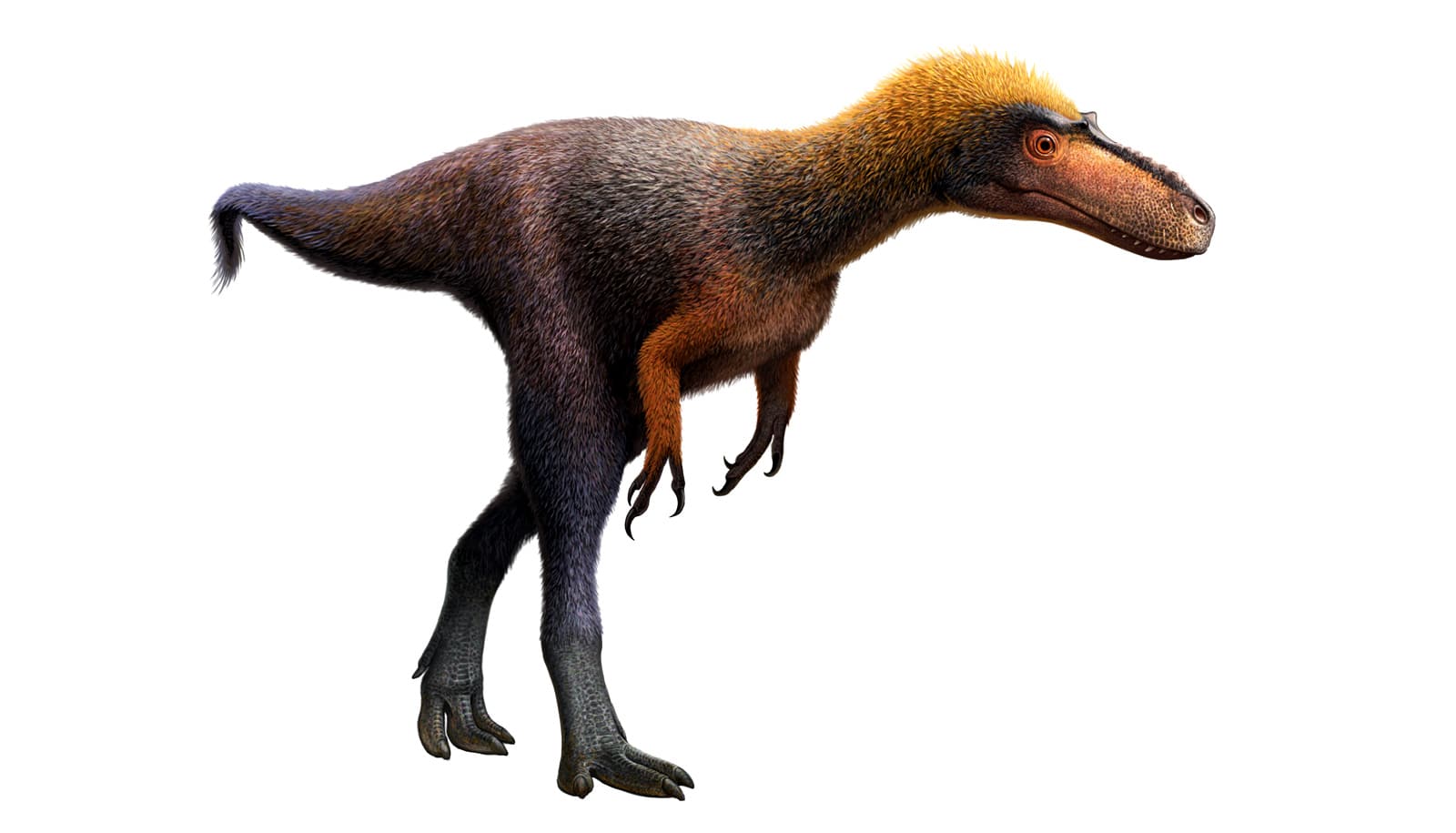

Theropod dinosaurs included the dominant bipedal predators of the Mesozoic Era, and plenty of research has explored the relationship between their locomotion and lifestyle.

Much of this work has focused on running speeds, but the new study argues that speed might not have ranked as the most important factor, especially for the biggest theropods.

For a new study, researchers gathered data on limb proportions, body mass, and gaits of more than 70 species of theropod dinosaurs. They then applied a variety of methods to estimate each dinosaur’s top speed as well as how much energy they expended while moving around at more relaxed walking speeds.

Smaller to medium-sized species appear to have adapted longer legs for faster running, in line with previous results. But for the real titans weighing over 1,000kg (more than 2,204 pounds), body size limited top running speed, so longer legs instead correlated with low-energy walking.

“Using locomotion models from a wide range of living animals, we were able to tease apart some dramatic differences in both running speeds and running efficiencies in carnivorous dinosaurs,” says Hans Larsson, director of McGill University’s Redpath Museum and one of the authors of the new study in PLOS ONE.

Running is important for hunters, but they generally spend much more time roaming around in search of food. The authors suggest that while speed was a major advantage for dinosaurs who needed to hunt prey and also escape predators, the biggest theropods relied more on efficiency while foraging.

Tyrannosaurus rex, whose long legs apparently adapted well for reduced energy expenditure while prowling for prey stood as champions of the giant theropods.

“Large bodied tyrannosaurs had distinctly efficient locomotion, even at multi-ton scales,” says Larsson. “This, coupled with our estimates of them running about 20 km/h (more than 12 mph) would have made them terrifying endurance predators—kind of like a pack of wolves, but with six-inch-long teeth in a mouth that could crush cars.”

Researchers from Mount Marty College in South Dakota contributed to the work.

Source: McGill University