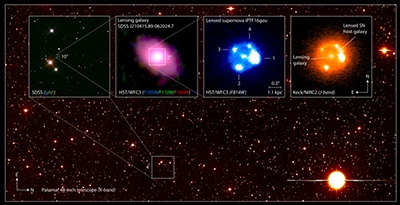

Astronomers have captured multiple images of a Type Ia supernova—the brilliant explosion of a star—appearing in four different locations in the sky. So far this is the only Type Ia discovered that has exhibited this effect.

The help of an automated supernova-hunting pipeline and a galaxy sitting 2 billion light years away from Earth that’s acting as a “magnifying glass” made the discovery possible. This phenomenon called “gravitational lensing” is an effect of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity—mass bends light. This means that the gravitational field of a massive object—like a galaxy—can bend light rays that pass nearby and refocus them somewhere else, causing background objects to appear brighter and sometimes in multiple locations.

Astrophysicists believe that if they can find more of these magnified Type Ias, they may be able to measure the rate of the universe’s expansion to unprecedented accuracy and shed some light on the distribution of matter in the cosmos.

Fortunately, by taking a closer look at the properties of this rare event, two Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory researchers have come up with a method—a pipeline— for identifying more of these so-called “strongly lensed Type Ia supernovae” in existing and future wide-field surveys. A paper describing their approach is published in Astrophysical Journal Letters. Meanwhile, a paper detailing the discovery and observations of the 4 billion year old Type Ia supernova, iPTF16geu, appears in Science.

Lucky detection

“It is extremely difficult to find a gravitationally lensed supernova, let alone a lensed Type Ia. Statistically, we suspect that there may be approximately one of these in every 50,000 supernovae that we identify,” says Peter Nugent, an astrophysicist in Berkeley Lab’s Computational Research Division (CRD) and an author on both papers. “But since the discovery of iPTF16geu, we now have some thoughts on how to improve our pipeline to identify more of these events.”

For many years, the transient nature of supernovae made them extremely difficult to detect. Thirty years ago, the discovery rate was about two per month. But thanks to the Intermediate Palomar Transient Factory (iPTF), a new survey with an innovative pipeline, these events are being detected daily, some within hours of when their initial explosions appear.

The process of identifying transient events, like supernovae, begins every night at the Palomar Observatory in Southern California, where a wide-field camera mounted on the robotic Samuel Oschin Telescope scans the sky. As soon as observations are taken, the data travel more than 400 miles to the Department of Energy’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is located at Berkeley Lab. At NERSC, machine learning algorithms running on the facility’s supercomputers sift through the data in real-time and identify transients for researchers to follow up on.

On September 5, 2016, the pipeline identified iPTF16geu as a supernova candidate. At first glance, the event didn’t look particularly out of the ordinary. Nugent notes that many astronomers thought it was just a typical Type Ia supernova sitting about 1 billion light years away from Earth.

Like most supernovae that are discovered relatively early on, this event got brighter with time. Shortly after it reached peak brightness (19th magnitude) Ariel Goobar, professor in experimental particle astrophysics at Stockholm University, decided to take a spectrum—or detailed light study—of the object. The results confirmed that the object was indeed a Type Ia supernova, but they also showed that, surprisingly, it was located 4 billion light years away.

A second spectrum taken with the OSIRIS instrument on the Keck telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, showed without a doubt that the supernova was 4 billion light years away, and also revealed its host galaxy and another galaxy located about 2 billion light years away that was acting as a gravitational lens, which amplified the brightness of the supernova and caused it to appear in four different places on the sky.

“I’ve been looking for a lensed supernova for about 15 years. I looked in every possible survey, I’ve tried a variety of techniques to do this and essentially gave up, so this result came as a huge surprise,” says Goobar, who is lead author of the Science paper. “One of the reasons I’m interested in studying gravitational lensing is that it allows you to measure the structure of matter—both visible and dark matter—at scales that are very hard to get.”

“Standard candles”

According to Goobar, the survey at Palomar was set up to look at objects in the nearby universe, about 1 billion light years away. But finding a distant Type Ia supernova in this survey allowed researchers to follow up with even more powerful telescopes that resolved small-scale structures in the supernova host galaxy, as well as the lens galaxy that is magnifying it.

“There are billions of galaxies in the observable universe and it takes a tremendous effort to look in a very small patch of the sky to find these kind of events. It would be impossible to find an event like this without a magnified supernova directing you where to look,” says Goobar. “We got very lucky with this discovery because we can see the small scale structures in these galaxies, but we won’t know how lucky we are until we find more of these events and confirm that what we are seeing isn’t an anomaly.”

Another benefit of finding more of these events is that they can be used as tools to precisely measure the expansion rate of the universe. One of the keys to this is gravitational lensing. When a strong gravitational lens produces multiple images of a background object, each image’s light travels a slightly different path around the lens on its way to Earth. The paths have different lengths, so light from each image takes a different amount of time to arrive at Earth.

“If you measure the arrival times of the different images, that turns out to be a good way to measure the expansion rate of the universe,” says Goobar. “When people measure the expansion rate of the universe now locally using supernovae or Cepheid stars they get a different number from those looking at early universe observations and the cosmic microwave background. There is tension out there and it would be neat if we could contribute to resolving that quest.”

According to Danny Goldstein, a UC Berkeley astronomy graduate student and an author of the Astrophysical Journal letter, there have only been a few gravitationally lensed supernovae of any type ever discovered, including iPTF16geu, and they’ve all been discovered by chance.

“By figuring out how to systematically find strongly lensed Type Ia supernovae like iPTF16geu, we hope to pave the way for large-scale lensed supernova searches, which will unlock the potential of these objects as tools for precision cosmology,” says Goldstein, who worked with Nugent to devise a method for finding them in existing and upcoming wide-field surveys.

The key idea of their technique is to use the fact that Type Ia supernovae are “standard candles”—objects with the same intrinsic brightness—to identify ones that are magnified by lensing. They suggest starting with supernovae that appear to go off in red galaxies that have stopped forming stars. These galaxies only host Type Ia supernovae and make up the bulk of gravitational lenses. If a supernova candidate that appears to be hosted in such a galaxy is brighter than the “standard” brightness of a Type Ia supernova, Goldstein and Nugent argue that there is a strong chance the supernova does not actually reside in the galaxy, but is instead a background supernova lensed by the apparent host.

“One of the innovations of this method is that we don’t have to detect multiple images to infer that a supernova is lensed,” says Goldstein. “This is a huge advantage that should enable us to find more of these events than previously thought possible.”

Using this method, Nugent and Goldstein predict that the upcoming Large Synoptic Survey Telescope should be able to detect about 500 strongly lensed Type Ia supernovae over the course of 10 years—about 10 times more than previous estimates. Meanwhile, the Zwicky Transient Facility, which begins taking data in August 2017 at Palomar, should find approximately 10 of these events in a three-year search. Ongoing studies show that each lensed Type Ia supernova image has the potential to make a 4 percent, or better, measurement of the expansion rate of the universe. If realized, this could add a very powerful tool to probe and measure the cosmological parameters.

“We are just now getting to the point where our transient surveys are big enough, our pipelines are efficient enough, and our external data sets are rich enough that we can weave through the data and get at these rare events,” adds Goldstein. “It’s an exciting time to be working in this field.”

IPTF is a scientific collaboration among Caltech; Los Alamos National Laboratory; the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; the Oskar Klein Centre in Sweden; the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel; the TANGO Program of the University System of Taiwan; and the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe in Japan. NERSC is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Source: UC Berkeley