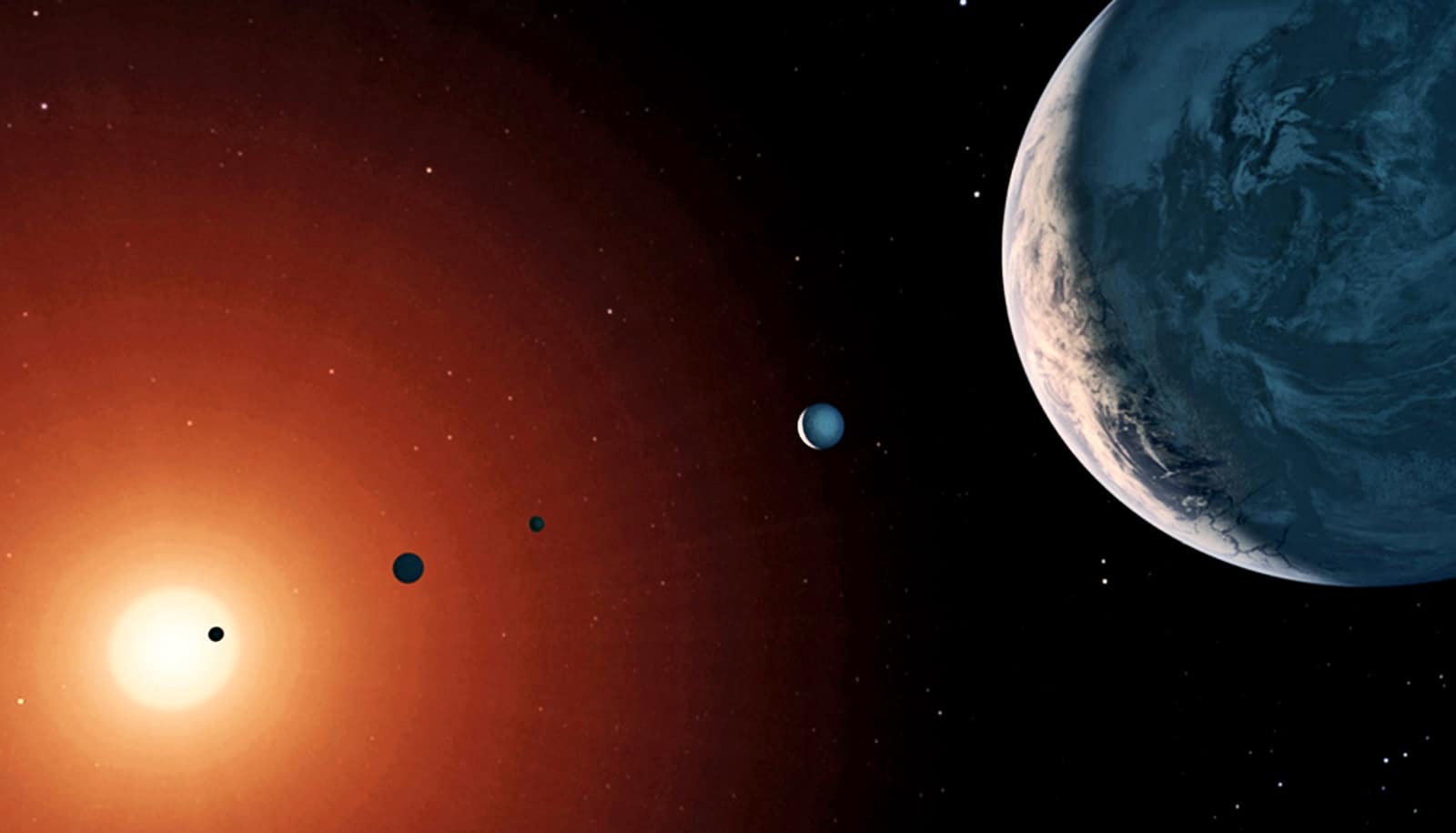

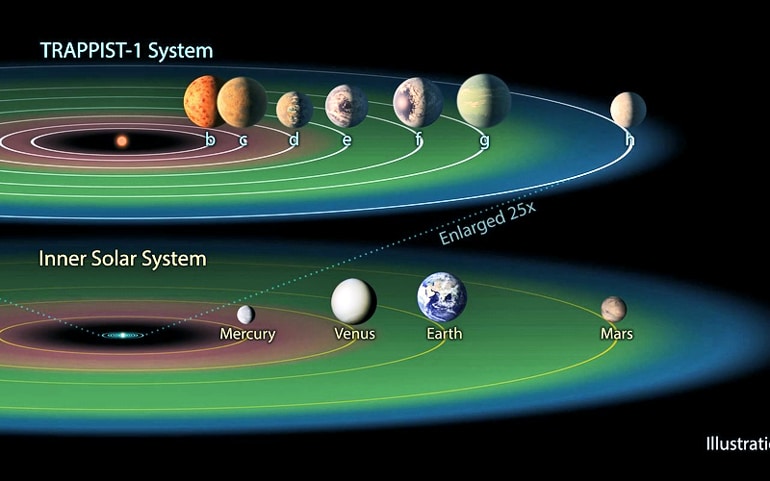

Two new studies may lead astronomers to redefine the habitable zone for TRAPPIST-1, a system where seven Earth-sized rocky planets orbit a cool star.

Since its discovery in 2016, planetary scientists have been excited about TRAPPIST-1. Three of the planets are in the habitable zone, the region of space where liquid water can flow on the planets’ surfaces.

The three planets in the habitable zone are likely facing a formidable opponent to life, new research finds: high-energy particles the star spews. For the first time, researchers have calculated how hard these particles are hitting the planets.

Meanwhile, another study finds that the gravitational tug-of-war the TRAPPIST-1 planets are playing with one another is raising tides on their surfaces, possibly driving volcanic activity or warming ice-insulated oceans on planets that are otherwise too cold to support life.

Both the paper about the high-energy particles and the paper on tugging tides appear in the Astrophysical Journal.

High-energy proton rain

The system’s star, TRAPPIST-1A, is smaller, less massive and 6,000 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than our 10,000-degree sun. It is also extremely active, meaning it emits huge amounts of high-energy protons—the same particles that cause auroras on Earth.

Federico Fraschetti, a lecturer in theoretical astroparticle physics in the planetary sciences and physics departments at the University of Arizona, and his team simulated the journeys of these high-energy particles through the magnetic field of the star. They found that the fourth planet—the innermost of the worlds inside the TRAPPIST-1 habitable zone—may be experiencing a powerful bombardment of protons.

“The flux of these particles in the TRAPPIST-1 system can be up to 1 million times more than the particles flux on Earth,” Fraschetti says.

This came as a surprise to the scientists, even though the planets are much closer to their star than Earth is to the sun. Magnetic fields carry the high-energy particles through space, and TRAPPIST-1A’s magnetic field tightly winds around the star.

“You expect that the particles would get trapped in these tightly wrapped magnetic field lines, but if you introduce turbulence, they can escape, moving perpendicularly to the average stellar field,” Fraschetti says.

Flares on the surface of the star cause turbulence in the magnetic field, allowing the protons to sail away from the star. Where the particles go depends on how the star’s magnetic field is angled away from its axis of rotation.

In the TRAPPIST-1 system, the most likely alignment of this field will bring energetic protons directly to the fourth planet’s face, where they could break apart complex molecules that are needed to build life—or perhaps they could serve as catalysts for the creation of these molecules.

While Earth’s magnetic field protects most of the planet from energetic protons that our sun emits, a field strong enough to deflect TRAPPIST-1’s protons would need to be improbably strong—hundreds of times more powerful than Earth’s. But this does not necessarily spell death for life in the TRAPPIST-1 system.

The TRAPPIST-1 planets are likely tidally locked, for one thing, meaning that the same hemisphere of each planet always faces the star, while perpetual night enshrouds the other.

“Maybe the night side is still warm enough for life, and it doesn’t get bombarded by radiation,” says Benjamin Rackham, a research associate with astronomy department who was not involved with either study.

Oceans could also shield against destructive high-energy protons, as deep water could absorb the particles before they tear apart the building blocks of life. Tides raised in these oceans and even in the rocks of the planets might have other interesting implications for life.

Tidal tug-of-war

On Earth, the moon doesn’t only raise tides in the oceans—tidal forces deform the spherical shape of Earth’s mantle and crust, as well. In the TRAPPIST-1 system, the planets are close enough together that scientists hypothesized the worlds might be raising tides on one another, as the moon does to Earth.

“When a planet or moon deforms from tides, friction inside it will create heating,” says Hamish Hay, a graduate student in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and lead author of the second study.

By calculating how the gravity of TRAPPIST-1’s planets would tug on and deform each other, Hay explored how much heat tides bring to the system.

TRAPPIST-1 is the only known system where planets can raise significant tides on each other because the worlds are so tightly packed around their star.

“It’s such a unique process that no one’s thought about in detail before, and it’s kind of amazing that it’s actually a thing that happens,” Hay says. In the past, scientists had only considered tides that the star raised.

Hay found that the inner two planets of the system come close enough together that they raise powerful tides on each other. It is possible the subsequent tidal heating may be strong enough to fuel volcanic activity, which can in turn sustain atmospheres. Though TRAPPIST-1’s innermost planets are likely too hot on their day side to sustain life, a volcano-fueled atmosphere could help move some heat to their otherwise-too-cold night side, warming it enough to keep living things from freezing.

The sixth planet in the system, called TRAPPIST-1g, is experiencing tidal tugging from both the star and the other planets. It is the only planet in the system where tidal heating due to the other planets is as strong as that the central star causes. If TRAPPIST-1g is an ocean world, like Europa or Enceladus in our own solar system, tidal heating could keep its waters warm.

M-dwarf star systems like TRAPPIST-1 offer astronomers the best opportunity to search for life outside the solar system, and Fraschetti and Hay’s studies may help scientists choose how to explore the system in the future.

“We need to really understand the suitability of these systems for life, and energetic particle fluxes and tidal heating are important factors to constrain our ability to do that,” Rackham says.

Source: University of Arizona