One in three people has a potentially nasty parasite hiding in the body—tucked away in tiny cysts that the immune system can’t eliminate and antibiotics can’t touch.

But new research reveals clues about how to stop it: Interfere with its digestion during this stubborn dormant phase.

If the discovery leads to new treatments, it could help prevent the parasitic disease toxoplasmosis, which sickens people worldwide.

For most people affected by it, Toxoplasma gondii causes only mild flu-like symptoms, often from food poisoning. After that initial infection, the parasite usually goes into cyst phase and remains in the person’s body for the rest of his or her life.

But in people with weak immune systems or pregnant women, the infection can cause problems immediately or after cysts awaken, damaging the brain, eyes, or a fetus they carry. Even healthy people can experience repeated retina damage if the parasite dwells in their eyes. Some evidence even links it to mental illness.

“The largest unmet need in toxoplasmosis is dealing with the chronic infection stage, which is the source of potentially severe disease through reactivation of the parasite from cysts,” says Vern Carruthers, leader of the research group and a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan.

“While there are reasonably good treatments for acute infections, and the immune system does a good job in healthy people of keeping it in check, no options exist for killing the cyst form to protect immunocompromised people and those who have had a previous eye infection.”

“The largest unmet need in toxoplasmosis is dealing with the chronic infection stage, which is the source of potentially severe disease through reactivation of the parasite from cysts.”

Eating its own innards

In Nature Microbiology, Carruthers and colleagues report that a molecule called cathepsin protease L, or CPL, is crucial to the parasite’s ability to survive the cyst phase and cause disease in mice. By interfering with CPL on a genetic level, and also using a drug, they disabled the parasite and kept it from surviving the cyst phase.

They also showed for the first time in an unmodified parasite that a form of digestion of the parasite’s own innards—called autophagy, and led by CPL—is crucial to Toxoplasma’s ability to persist.

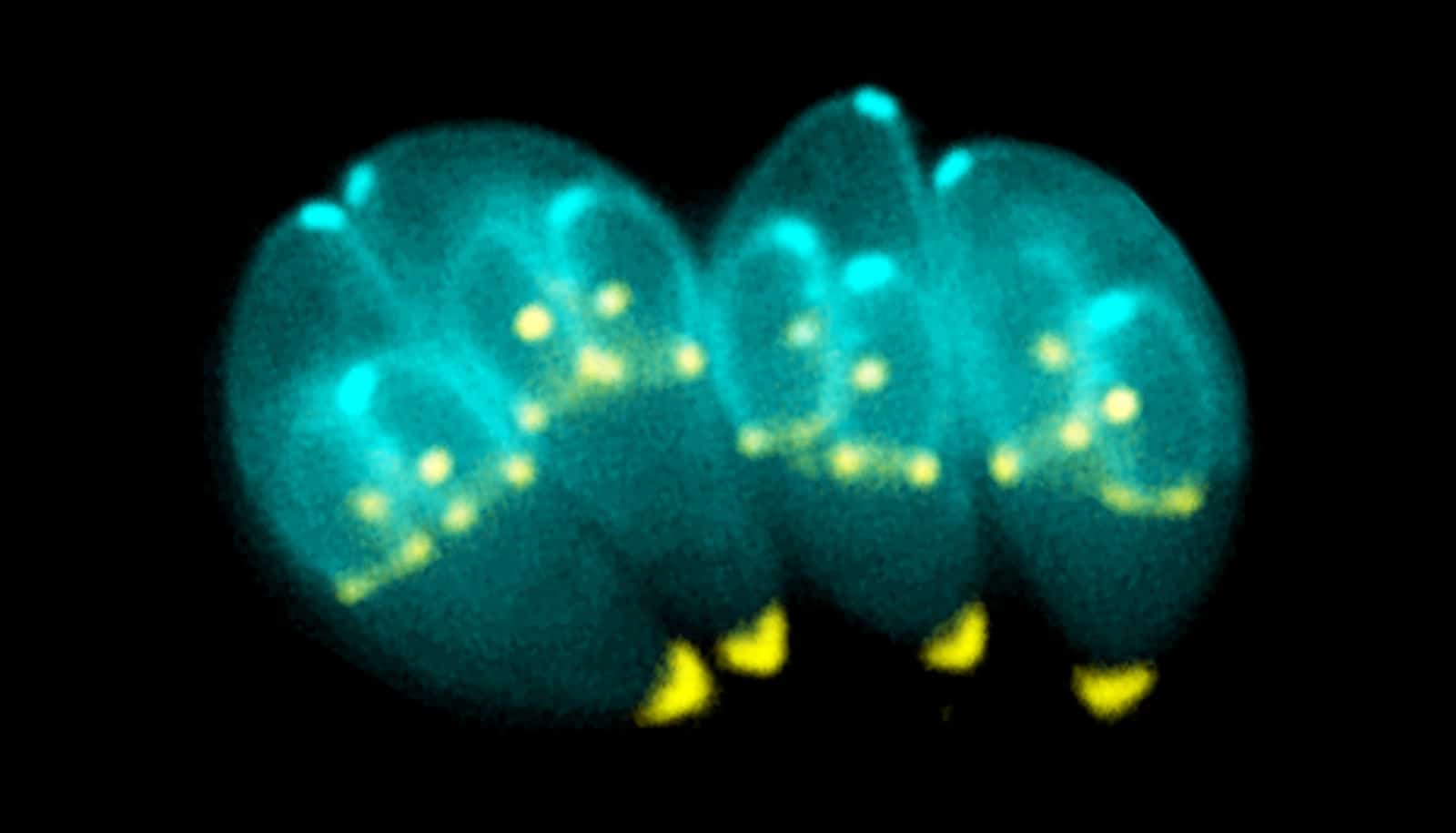

Carruthers and his team figured out the crucial role of CPL and the importance of autophagy during several experiments on the cysts, which contain forms of the parasites called bradyzoites.

CPL is a protease, or protein-digesting molecule. It may help Toxoplasma cysts survive by digesting the parasite’s own innards or by digesting materials that can enter the cyst from outside. When CPL was disabled, the vacuolar compartment that serves as the parasite’s “stomach” experienced a buildup of materials that disabled the entire cyst.

Do parasitic worms help keep arteries young?

For the new paper, the team temporarily opened holes in the parasite’s membrane and knocked out the existing copy of the CPL gene, or added a changed gene to make an altered form of CPL. This “gene therapy” approach allows them to study the impact of altered or absent CPL activity.

In the litter box

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has named toxoplasmosis a “neglected parasitic infection” and a target for public health action. In addition to citing a high worldwide infection rate, the CDC estimates that 1 in 10 Americans carries the parasite.

Undercooked meat can spread Toxoplasma bradyzoite cysts, and the parasite is often transmitted to humans through cat feces that contain another cyst form.

That’s why public health authorities advise pregnant women not to change cat litter boxes, and advise anyone who eats meat to consume it only fully cooked.

The key danger from toxoplasmosis is that it’s one of the few infections capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier. That means it can get into the nervous system, including the retina, spinal cord, and brain. It can also hide out in muscle tissue of both humans and animals.

Tropical parasite threatens health of kids in Arctic

Carruthers’ group used a drug to disable the parasite in infected human cells. But that drug cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, so it will not be useful for treatment. They are working with a group led by Scott Larsen, in the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy’s medicinal chemistry department to look for other drugs that can inhibit CPL.

“This paper is the proof of principle that protein digestion is important to the cyst stage of the parasite’s life cycle, though we don’t yet know if it digests to generate energy or to remove unneeded materials,” says Carruthers. “We still have much to learn about Toxoplasma, including how much of a barrier the cyst membrane is and whether we can inhibit it from outside.”

If the parasites in the cysts aren’t taking in “food” from outside themselves, the autophagy process may be a self-preservation effort, similar to the wasting away of starving humans as their bodies consume muscle to stay alive. Blocking this process would make the cyst starve faster.

Or, if food does make it in to cysts, disabling CPL could result in a microscopic “bowel obstruction” where waste and unused food build up to a lethal level.

Carruthers, whose team has studied the parasite for years, notes that any future drug aimed at the tissue cyst stage would have to travel through the cyst membrane and the blood-brain barrier, too.

Funding came from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.

Source: University of Michigan