Earth’s earliest primates dwelled in treetops, not on the ground, according to an analysis of a 62-million-year-old partial skeleton discovered in New Mexico.

The skeleton—the oldest ever found—was discovered in the San Juan Basin by Thomas Williamson, curator of paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, and his twin sons, Taylor and Ryan.

Torrejonia, a small mammal from an extinct group of primates called plesiadapiforms, had skeletal features adapted to living in trees, including flexible joints for climbing and clinging to branches.

Researchers had previously proposed that plesiadapiforms in Palaechthonidae, the family to which Torrejonia belongs, were terrestrial based on details from cranial and dental fossils consistent with animals that nose about on the ground for insects.

“This is the oldest partial skeleton of a plesiadapiform, and it shows that they undoubtedly lived in trees,” says lead author Stephen Chester, an assistant professor at Brooklyn College, City University of New York, and curatorial affiliate of vertebrate paleontology at the Yale Peabody Museum, who began this collaborative research while at Yale University studying for his PhD.

Two amazing fossil skeletons belong to new lizard

“We now have anatomical evidence from the shoulder, elbow, hip, knee, and ankle joints that allows us to assess where these animals lived in a way that was impossible when we only had their teeth and jaws.”

The findings, published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, support the hypothesis that plesiadapiforms, which first appear in the fossil record shortly after the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, were the earliest primates. The data also provide additional evidence that all of the geologically oldest primates known from skeletal remains, encompassing several species, were arboreal.

“To find a skeleton like this, even though it appears a little scrappy, is an exciting discovery…”

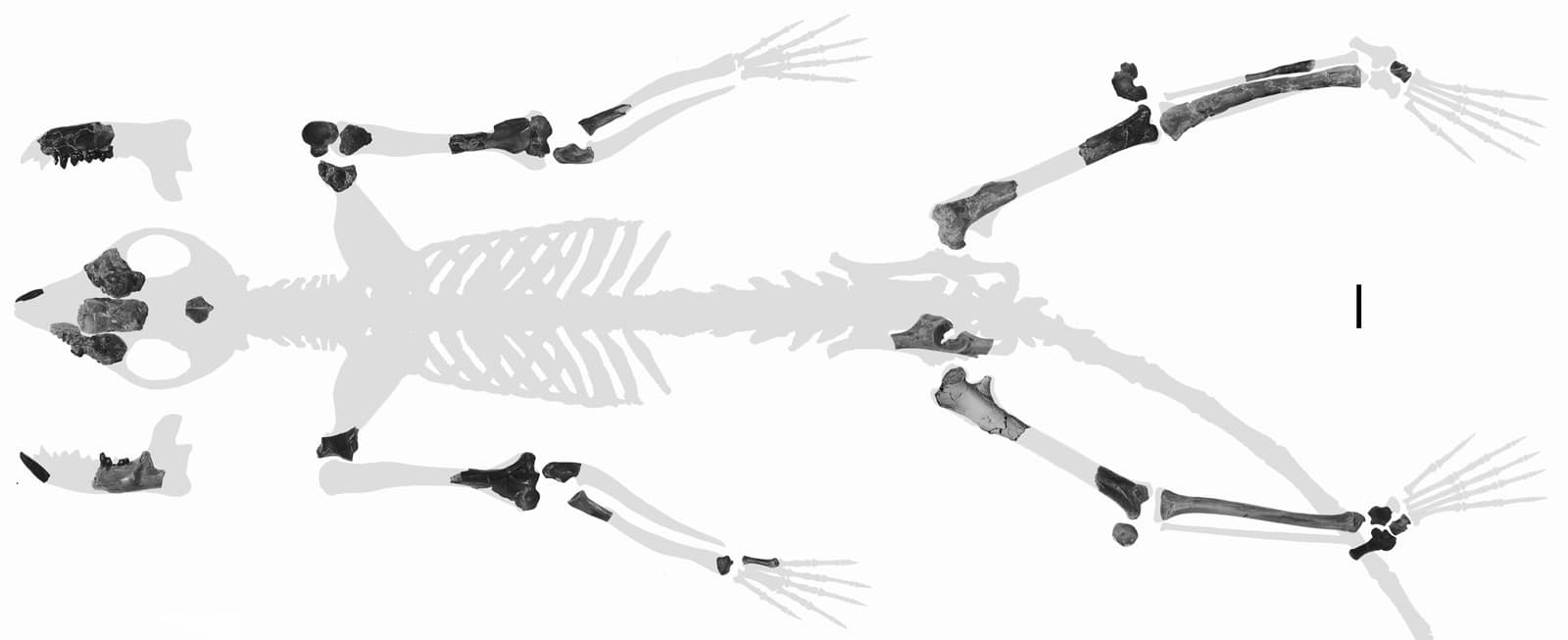

The partial skeleton consists of over 20 separate bones, including parts of the cranium, jaws, teeth, and portions of the upper and lower limbs. The presence of associated teeth allowed Williamson, a coauthor of the study, to identify the specimen as Torrejonia because the taxonomy of extinct mammals is based mostly on dental traits, says Eric Sargis, professor of anthropology at Yale and senior author of the study.

“To find a skeleton like this, even though it appears a little scrappy, is an exciting discovery that brings a lot of new data to bear on the study of the origin and early evolution of primates.”

Palaechthonids, and other plesiadapiforms, had outward-facing eyes and relied on smell more than living primates do today—details suggesting that plesiadapiforms are transitional between other mammals and modern primates, Sargis says.

The site where the partial skeleton was discovered, known as the Torrejon Fossil Fauna Area, is a remote area in northwestern New Mexico administered by the federal Bureau of Land Management. These public lands are managed to protect the scientific value of the paleontological resources found there. The collection of the Torrejonia took place under a permit from the agency.

Jonathan Bloch of the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida and Mary Silcox of the anthropology department at the University of Toronto Scarborough are coauthors.

The National Science Foundation supported the work.

Source: Yale University