Children as young as three are already beginning to recognize and follow important rules and patterns governing how letters in the English language fit together to make words, a new study suggests.

The study provides new evidence that children start to learn about some aspects of reading and writing at a very early age.

…children are clearly listening to the word and trying to use letters to symbolize some of the sounds within it…

“Our results show that children begin to learn about the statistics of written language, for example about which letters often appear together and which letters appear together less often, before they learn how letters represent the sounds of a language,” says study coauthor Rebecca Treiman, a professor of psychological and brain sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

An important part of learning to read and spell is learning about how the letters in written words reflect the sounds in spoken words. Children often begin to show this knowledge around 5 or 6 years of age when they produce spellings such as BO or BLO for “blow.”

We tend to think that learning to spell doesn’t really begin until children start inventing spellings that reflect the sounds in spoken words—spellings like C or KI for “climb”. These early invented spellings may not represent all of the sounds in a word, but children are clearly listening to the word and trying to use letters to symbolize some of the sounds within it, Treiman says.

As children get older, these sound-based spellings improve. For example, children may move from something like KI for “climb” to something like KLIM.

“Many studies have examined how children’s invented spellings improve as they get older, but no previous studies have asked whether children’s spellings improve even before they are able to produce spellings that represent the sounds in words,” Treiman says.

“Our study found improvements over this period, with spellings becoming more wordlike in appearance over the preschool years in a group of children who did not yet use letters to stand for sounds,” she says.

Treiman’s study analyzed the spellings of 179 children from the United States (age 3 years, 2 months to 5 years, 6 months) who were prephonological spellers. That is, when asked to try to write words, the children used letters that did not reflect the sounds in the words they were asked to spell, which is common and normal at this age.

Toddlers pick up lots of grammar around 24 months

On a variety of measures, the older prephonological spellers showed more knowledge about English letter patterns than did the younger prephonological spellers. When the researchers asked adults to rate the children’s productions for how much they looked like English words, they found that the adults gave higher ratings, on average, to the productions of older prephonological spellers than to the productions of younger prephonological spellers.

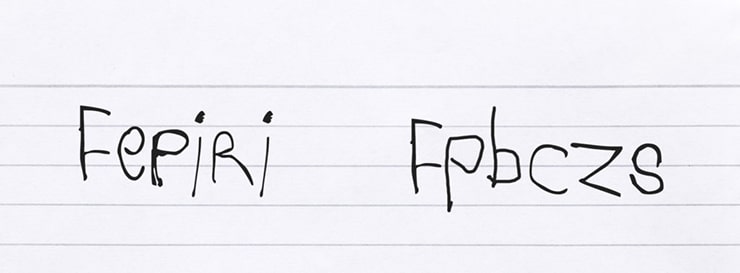

The productions of older prephonological spellers also were more word-like on several objective measures, including length, use of different letters within words, and combinations of letters. For example:

“While neither spelling makes sense as an attempt to represent sounds, the older child’s effort shows that he or she knows more about the appearance of English words,” Treiman says.

The findings are important, Treiman says, because they show that exposure to written words during the three-to-five-year age range may be important in getting children off to a strong start with their reading, writing, and spelling skills.

“Our results show that there is change and improvement with age during this period before children produce spellings that make sense on the basis of sound.” Treiman says.

“In many ways, the spellings produced during this period of time are more wordlike when children are older than when they are younger. That is, even though the spellings don’t represent the sounds of words, they start looking more like actual words,” she says.

“This is pretty interesting, because it suggests that children are starting to learn about one aspect of spelling—what words look like—from an earlier point than we’d given them credit for,” she says. “It opens up the possibility that educators could get useful information from children’s early attempts to write—information that could help to show whether a child is on track for future success or whether there might be a problem.”

How reading to babies turns babble into language

The study appears in the journal Child Development. Grants from the NSF and the NIH supported this research.