Nearly 15,000 miles of new Asian roads will be built in tiger habitat by mid-century, deepening the big cat’s extinction risk, according to a new study.

Researchers say the findings highlight the need for bold new conservation measures now.

Researchers used a recently developed global roads dataset to calculate the extent and potential effects of existing and planned road networks across the nearly 450,000-square-mile, 13-country range of the globally endangered tiger.

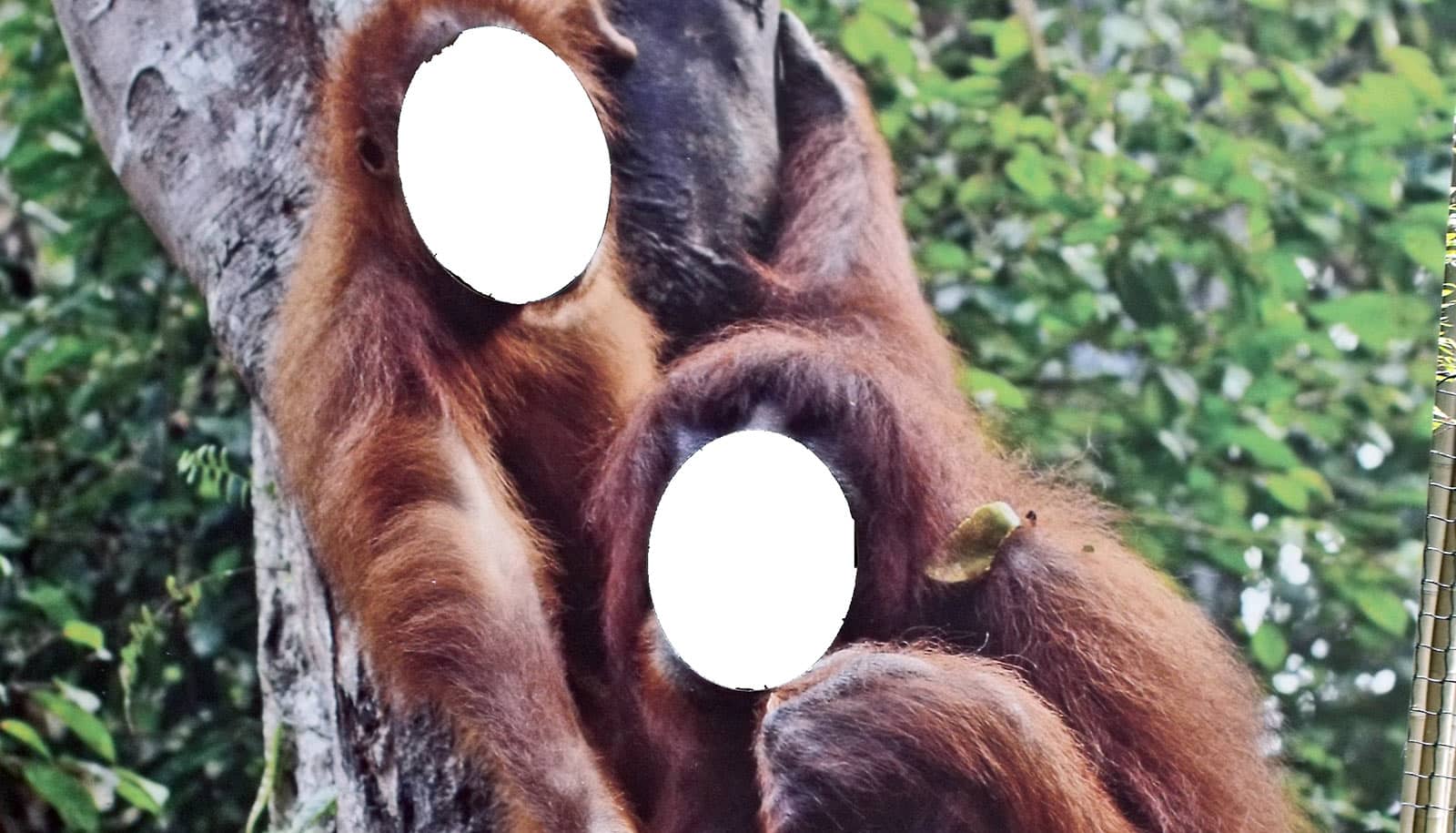

Fewer than 4,000 tigers remain in the wild, found mainly in South Asia and Southeast Asia. These regions will experience accelerating pressure from human development in coming years, researchers say.

Road construction often exacerbates all three of the main threats to tigers: prey depletion, habitat degradation, and poaching.

Tigers vs. roads

Existing roads are pervasive throughout tiger habitat, totaling 83,300 miles (134,000 kilometers) in Tiger Conservation Landscapes (TCLs), blocks of habitat across the animal’s range considered crucial for recovery of the species, according to the study in Science Advances.

The finding is “a highly troubling warning sign for tiger recovery and ecosystems in Asia,” the researchers say.

The researchers calculated three measures—road density, distance to the nearest road, and relative mean species abundance—to characterize how existing road networks influence tiger habitat. They calculated current road densities for all 76 TCLs and summarized those estimates by country and protection status.

In addition, they used published forecasts of global road expansion to calculate the length of new roads that might exist in tiger habitat by 2050, for each of the 13 tiger-range countries.

Key findings include:

- The 83,300 miles of current road networks within tiger habitat may decrease the abundance of tigers and their prey by more than 20%.

- 43% of the area where tiger breeding occurs and 57% of the area in TCLs are within 3.1 miles (5 km) of a road, a proximity that can negatively affect tigers and their prey.

- Nearly 15,000 miles of new roads will be built in TCLs by 2050, stimulated through major investment projects such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

- Road densities are, on average, 34% greater in nonprotected portions of TCLs than in strictly protected parts, indicating that road density increases with the relaxation of protection status.

- Road densities varied widely across tiger-range countries. China’s mean road density in TCLs is nearly eight times greater than Malaysia’s, for example.

“Our analysis demonstrates that, overall, tigers face a ubiquitous and mounting threat from road networks across much of their 13-country range,” says Neil Carter, assistant professor at the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan.

“Tiger habitats have declined 40% since 2006, underscoring the importance of maintaining roadless areas and resisting road expansion in places where tigers still exist, before it is too late. Given that roads will pose a pervasive challenge to tiger recovery in the future, we urge decision makers to make sustainable road development a top priority.”

Tiger ‘islands’

The world’s remaining tigers are concentrated in a small number of source populations—areas with confirmed current presence of tigers and evidence of breeding—across the animal’s geographic range.

Even a small amount of road construction could disproportionately affect tiger recovery by permanently isolating tiger populations, creating tiger “islands,” the researchers say.

Protecting tigers is a global conservation priority, exemplified by a landmark international initiative, called TX2, with the goal of doubling global tiger numbers between 2010 and 2022. And tigers are considered a conservation flagship species, a popular, charismatic animal that serves as a symbol and rallying point to stimulate conservation awareness and action.

Even so, few studies have assessed the impacts of roads on tigers and their recovery, limiting the impact of tiger conservation planning.

Most previous “road ecology” studies of tigers have focused on localized patterns of wildlife mortality or behavior associated with road design. The new study, in contrast, estimates road impacts on wildlife at broad scales. It is the first study to include baseline indices on the threat from existing and future roads in tiger habitat.

“This research opens the door to build partnerships at the regional scale to better mitigate existing roads and to develop greener road designs for the next century of infrastructure development,” says coauthor Adam Ford, a wildlife ecologist at the University of British Columbia.

The researchers say their metrics provide tools to support sustainable road development, enabling rapid risk assessment for roads passing through tiger habitat, including roads planned as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The BRI, a global development strategy adopted by the Chinese government in 2013, involves infrastructure projects in dozens of countries in Asia, Europe, and Africa. The rush to build major new roads throughout the forested regions of South Asia and Southeast Asia, financed through the initiative, could have severe impacts on tigers, according to Carter and his colleagues.

But the BRI could become an important partner in tiger preservation, according to the researchers, by adopting biodiversity conservation as one of its core values. That would set the stage for the BRI to plan and implement a network of protected areas and wildlife corridors to safeguard tigers from road impacts.

The 13 tiger-range countries are Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Additional coauthors are from Boise State University and the University of Michigan. The National Science Foundation’s Idaho EPSCoR Program and the Canada Research Chairs program funded the work.

Source: University of Michigan