Newly digitized vintage film doubles how far back scientists can peer into the history of underground ice in Antarctica.

The film reveals that a warming ocean is thawing an ice shelf on Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica faster than previously thought, a new study shows.

Researchers, who compared ice-penetrating radar records of Thwaites Glacier with modern data, say the findings will contribute to predictions for sea-level rise that would affect coastal communities around the world.

“By having this record, we can now see these areas where the ice shelf is getting thinnest and could break through,” says lead author Dustin Schroeder, an assistant professor of geophysics at Stanford University’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences who led efforts to digitize the historical data from airborne surveys conducted in the 1970s. “This is a pretty hard-to-get-to area and we’re really lucky that they happened to fly across this ice shelf.”

Historical film

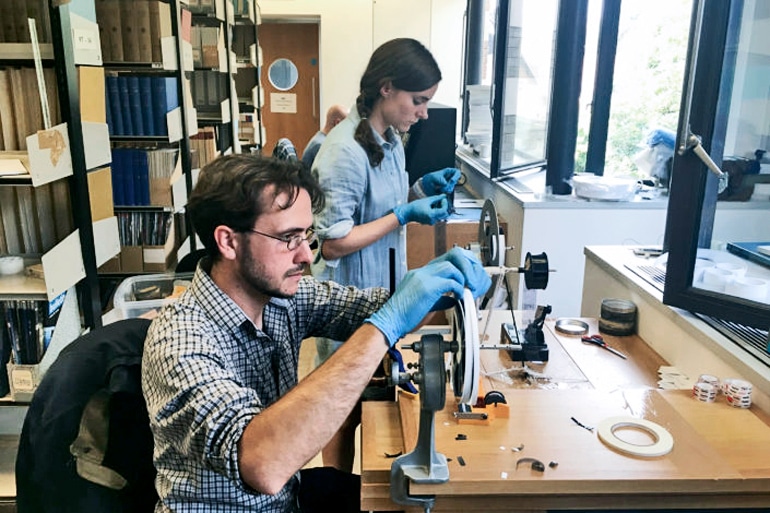

Researchers digitized about 250,000 flight miles of Antarctic radar data originally captured on 35mm optical film between 1971 and 1979 as part of a collaboration between Stanford and the Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) at Cambridge University in the UK.

Scientists released the data to an online public archive through Stanford Libraries, enabling others to compare it with modern radar data in order to understand long-term changes in ice thickness, features within glaciers, and baseline conditions over 40 years.

The information the historic records provided will help efforts like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its goal of projecting climate and sea-level rise for the next 100 years. Being able to look back 40 to 50 years at subsurface conditions rather than just the 10 to 20 years modern data provided will help scientists better understand what has happened in the past and make more accurate projections about the future, Schroeder says.

“You can really see the geometry over this long period of time, how these ocean currents have melted the ice shelf—not just in general, but exactly where and how,” says Schroeder, who is also a faculty affiliate at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. “When we model ice sheet behavior and sea-level projections into the future, we need to understand the processes at the base of the ice sheet that made the changes we’re seeing.”

The film was originally recorded in an exploratory survey using ice-penetrating radar, a technique still used today to capture information from the surface through the bottom of the ice sheet. The radar shows mountains, volcanoes, and lakes beneath the surface of Antarctica, as well as layers inside the ice sheet that reveal the history of climate and flow.

Comparing past and present

The researchers identified several features beneath the ice sheet that had previously only been observed in modern data, including ash layers from past volcanic eruptions captured inside the ice and channels where water from beneath the ice sheet is eroding the bottom of ice shelves. They also found that one of these channels had a stable geometry for over 40 years, information that contrasts their findings about the Thwaites Glacier ice shelf, which has thinned from 10 to 33% between 1978 and 2009.

“The fact that we were able to have one ice shelf where we can say, ‘Look, it’s pretty much stable. And here, there’s significant change’—that gives us more confidence in the results about Thwaites,” Schroeder says.

The scientists hope the findings demonstrate the value of comparing this historical information to modern data to analyze different aspects of Antarctica at a finer scale. In addition to the radar data, the Stanford Digital Repository includes photographs of the notebooks from the flight operators, an international consortium of American, British, and Danish geoscientists.

“It was surprising how good the old data is,” Schroeder says. “They were very careful and thoughtful engineers and it’s much richer, more modern looking, than you would think.”

The study appears in PNAS. Additional coauthors are from Stanford, the University of Colorado Boulder, the University of Cambridge, Imperial College London, and the University of Edinburgh. NASA, the National Science Foundation, and Stanford University funded the work.

Source: Stanford University