Thrill seekers and daredevils thrive on the terrifying because of their high-sensation-seeking personalities, according to a new book.

The new book, Buzz! Inside the Minds of Thrill-Seekers, Daredevils and Adrenaline Junkies (Cambridge University Press, 2019) digs into the stories of real-life adventurers, such as a scaler of skyscrapers, known as “Spider Man,” who enjoys hanging from great heights suspended by only his fingers, to examine what thrill seekers get out of scary experiences.

The book is the culmination of years of research into high sensation-seeking people by author Kenneth Carter, a professor of psychology at Oxford College at Emory University and a self-described low sensation-seeking personality type. That said, he appreciates the psychology of more adventurous people and their value to society.

To find out if you’re a thrill-seeker or a chill-seeker, take Carter’s online quiz.

“It’s such a fun topic, and fascinating to me,” he says. “Everybody knows someone who is a high sensation-seeker, even if they’re not one themselves. To me, it’s thrilling to listen to their stories and get an idea of what’s going on inside their heads. Their motives are not what most people may assume.”

“One of the goals of psychology is to help people understand themselves and their loved ones better,” says Carter, who’s also designed and teaches a course on the psychology of the thrill-seeking personality offered as a massive online open course. “I hope that readers who are thrill-seekers, or those that have a friend or a relative who is one, will gain insights from the book.”

Craving intense experiences

As Carter began to wonder why he craves calmness while some individuals seem drawn to chaos, he came across the research of Martin Zuckerman of the University of Montreal, who discovered that a subset of people thrives in environments that are overwhelming and frightening to others.

Zuckerman was one of the first people to identify thrill-seeking as an important personality trait. He created a sensation-seeking scale to determine where individuals fall on a continuum of those who thrive on intense experiences and those who prefer to avoid them.

A defining characteristic of a high scorer on the sensation-seeking scale is someone who craves intense experiences despite physical or social risk. It’s a myth, however, to assume that they don’t value their lives, Carter says.

“They don’t have a death wish,” he stresses, “but seemingly a need for an adrenaline rush, no matter what.”

The ‘flow state’ of thrill seeking

Carter’s fascination with the topic drove him to seek out the personal stories of high sensation-seekers, even when that meant he had to deal with his own fears, such as heights. He met up with an adventurer named Nick on a bridge in Twin Falls, Idaho as Nick strapped on a parachute and leapt over the edge for a sport called BASE jumping.

“My heart jumped in my chest. My breathing was shallow,” Carter writes. “I was clearly rattled—and I was just watching.”

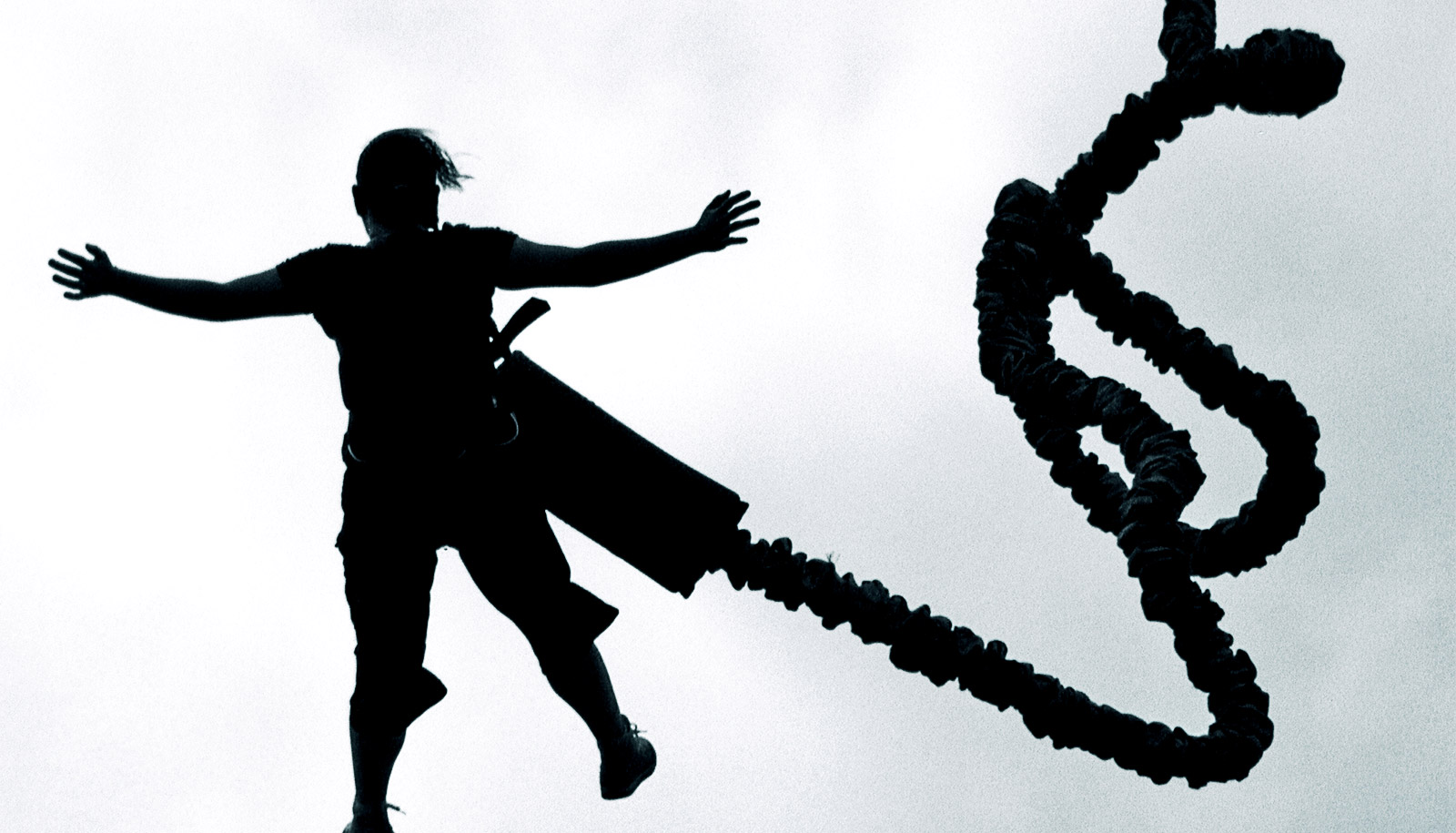

Buzz! also treats readers to an interview with an ice climber named Will Gadd who became the first to scale the frozen face of Niagara Falls. And then there’s Matt Davis, a self-described everyday guy who also happens to be “a mudder,” someone who enjoys obstacle race courses that involve belly-crawling under barbed wire and dashing through tents filled with tear gas. And Jeb Corliss, famous for donning a wingsuit—which transforms him into what Carter describes as “a giant flying squirrel”—and jumping off the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

They explain that these activities allow them to enter a flow state—an energized focus on the joy of the moment. High sensation-seekers need more stimulation than the average person to enter this state and studies suggest genetics may play a role. As Nick the BASE jumper told Carter: “From the time I was five years old, I just always wanted to fly. I can’t really explain it, it’s just part of my DNA. It’s just something I need to do.”

High sensation-seekers are not always extreme athletes. The personality trait can influence people’s lifestyles in all sorts of ways, Carter explains, from the way they think to the way they eat, socialize, and travel.

He writes about “fearless foodies,” people who “seek sensations in bowls of chicken hearts, goat brains, and pig blood stew, not because these foods are part of their cultural norms, but because they’re there.” And a blogger who calls herself the White Rabbit who set off to “follow the sun” on a 300-day journey during which she carried no money, but tons of chutzpah to convince strangers to let her crash on their couches.

One key takeaway from the book is that high sensation-seeking is a personality trait that can be positive or negative. Carter concludes that the good aspects more often outweigh the bad. For example, those with the ability to perform well in chaotic situations may excel as emergency medical technicians or even astronauts.

High sensation-seekers also serve as inspiration for the less adventurous, Carter adds. They are vivid reminders of the joy of “going with the flow,” the need to feel awe and the fun of occasionally trying new things.

That doesn’t necessarily mean watching the latest horror movie. Or putting on a wingsuit and jumping off a cliff.

“Going to a museum and looking at art brings me a sense of awe,” Carter says. “I’m happy with that. And maybe I’ll try ordering something I haven’t had before in a restaurant. You have to start small.”

Source: Emory University