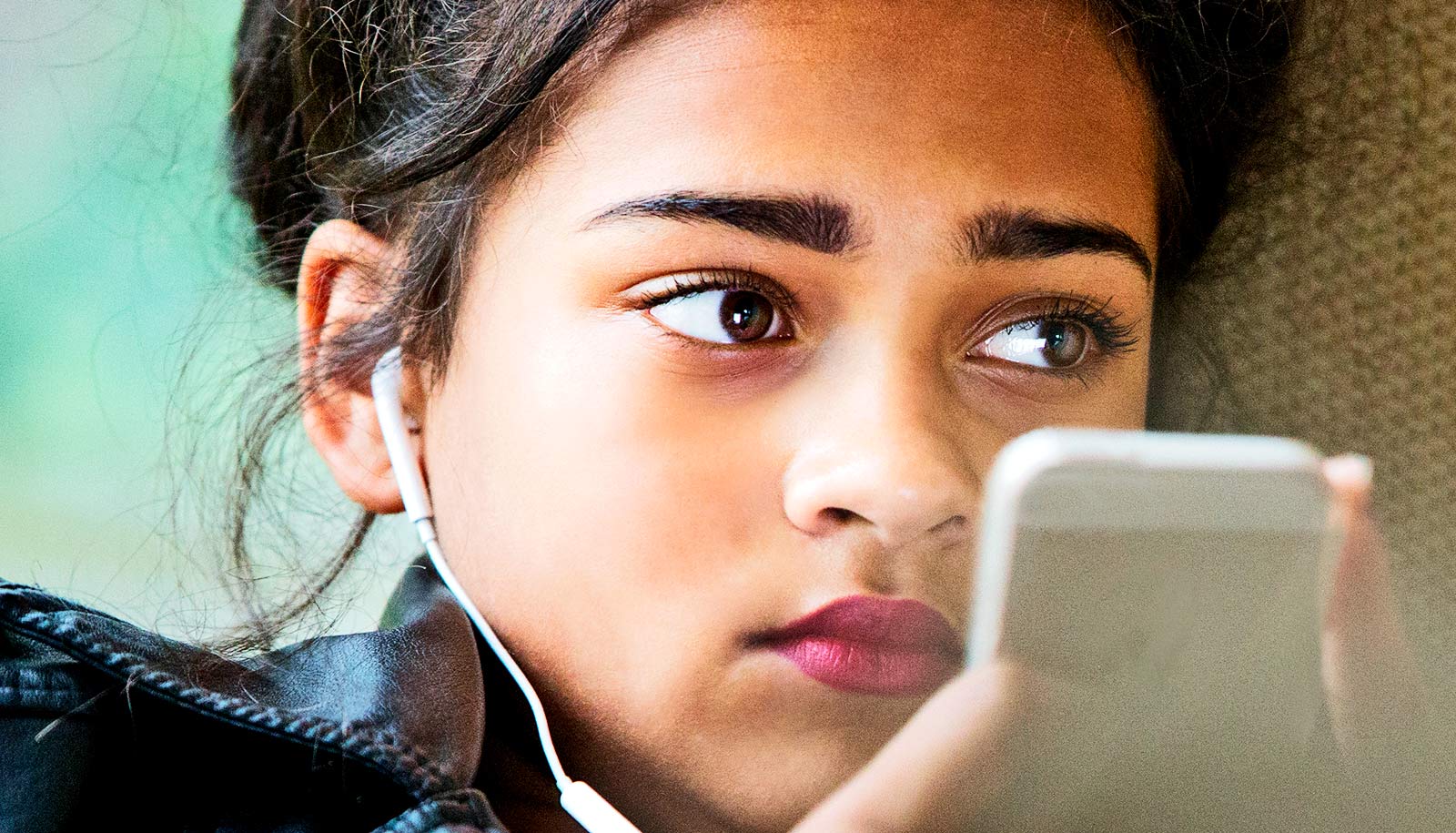

The language that teen girls use in texts and on social media posts reflects day-to-day changes in their moods, according to new research.

Those linguistic clues could be used to build digital tools that can identify when someone is struggling and connect them with timely support.

Many mental health problems first emerge during the teen years, says Nick Allen, professor of psychology and director of the Center for Digital Mental Health at the University of Oregon.

“This is a way of taking therapy out of the office and into people’s daily lives.”

“It’s a really important period of life for prevention,” Allen says. “We want to understand if there are ways we might reach out to teens and support them, in a way that works for them.”

Figuring out when someone is having a difficult time can be hard. As kids turn into teenagers, peer support becomes increasingly important. So the way teens interact informally with friends via their smartphones might more closely reflect their emotional state than what they share with a parent at the dinner table, Allen says.

Red flag language

The researchers worked for a month with 30 adolescent girls, ages 11 to 15, who are participants in a larger, long-term study of teen girls in the Eugene, Oregon area.

Researchers analyzed more than 22,000 messages the teen girls sent across a variety of social media platforms, including text messaging and social apps like TikTok and Snapchat. Participants rated their own moods every day and were screened for depression and anxiety.

From that data, researchers identified certain linguistic features that reflected fluctuations in the teens’ mental health. In particular, increased use of self-focused language—statements including first-person pronouns such as “I,” “me,” “my”—correlated to days when the message-sender’s mood was lower than usual.

Girls who reported lower moods than their peers also were more likely to use language focused on the present and the future, rather than the past. For teens reporting higher overall moods, language oriented to the past indicated a better day.

The sheer amount of text, regardless of content, also yielded clues to the blues: In teens who reported lower moods overall throughout the course of the study, a particularly rough day correlated with a greater number of words sent.

Looking ahead

“The ultimate goal is to have some way to proactively reach out and provide support when kids need it most,” says Allen, who is part of the psychology department. “If we can do that in a way that’s ethical, the possibilities are quite exciting, in terms of what we can do to support people.”

For example, someone could feel fine during their weekly therapy appointment but might be struggling a few days later.

A smartphone app attuned to their language patterns could detect a downward mood shift and send a well-timed reminder to go for a walk, make plans with a friend, or stop scrolling mindlessly through social media. That won’t cure depression, Allen says, but it could give someone enough of a nudge to put the brakes on a negative spiral and help them get back to their baseline.

“It’s hard to think of what you need to do when you’re in distress,” Allen says. “This is a way of taking therapy out of the office and into people’s daily lives.”

The paper appears in Clinical Psychological Science.

Source: Laurel Hamers for University of Oregon