Two education researchers have some insights on the rising rates of teacher resignation and growing concerns for the future of the field.

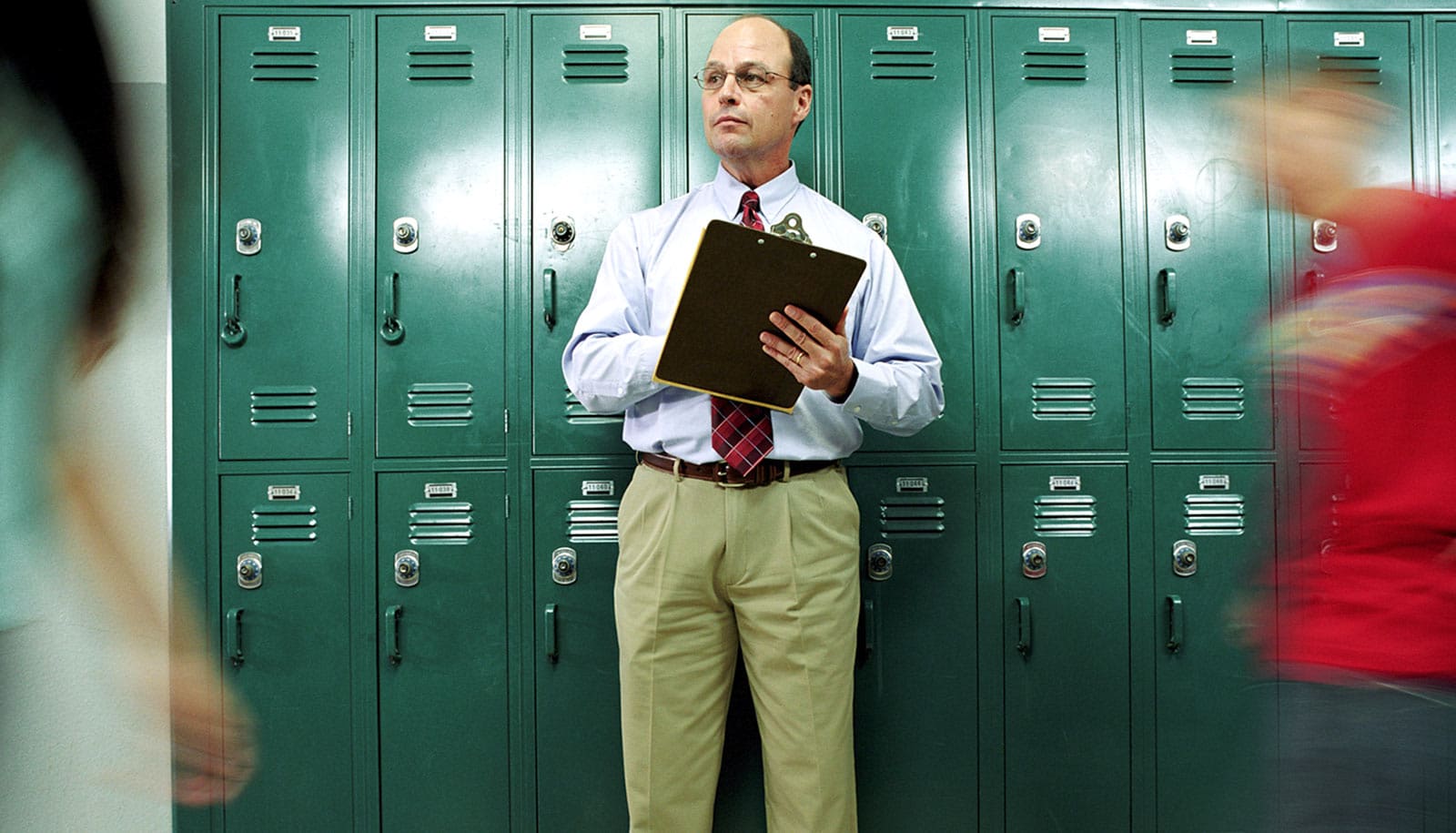

Teachers have one of the most important roles in society, yet they have always been up against a host of challenges–both inside and outside of their classrooms.

From low wages, to extended hours, to the pressures of meeting the unique needs of each student, the profession demands that teachers not only provide a strong educational foundation, but also bring their whole selves to work each day they arrive at school.

Add in a global pandemic, and the challenges have only continued to grow.

Many educators have spent the last two years navigating online teaching and learning, rising student mental health crises, mounting requests from school administrators, concerns for their own physical wellbeing in the classroom, and much more. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, about 20% of teachers seek second jobs to compensate for their salaries.

Conversations surrounding teacher burnout are circulating in the news, with more teachers than ever before saying they are considering leaving the field for good. And when tragedy strikes, like the devastating mass shooting that occurred on May 24 at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, educators are often left navigating unthinkable moments of anguish for themselves, their students, and their communities at large.

So, where do we go from here?

Education experts Olivia Chi and Andrew Bacher-Hicks have some ideas about teacher burnout and how to uplift educators in a post-pandemic world. Chi is an assistant professor at Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development where she focuses on the economics of education, educational leadership, and policy studies to reduce educational inequality. Bacher-Hicks is also an assistant professor at Wheelock where he specializes in K-12 education policy in the United States.

The pair recently published a working paper on Massachusetts teacher turnover during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their research, co-written by Wheelock postdoctoral associate Alexis Orellana, examined the obstacles this group of educators faced and improvements that could be made to ensure long-term retention and success in the field.

Here, Chi and Bacher-Hicks expand on some of these pandemic-induced pressures, and the areas where support is needed most:

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, has the US education system experienced a “mass exodus” of teachers? If so, do you predict this to continue ahead of the next school year?

In general, we have not seen a “mass exodus” of teachers during the pandemic. During the first year of the pandemic, teacher turnover rates were remarkably consistent with turnover rates before the pandemic. At the beginning of the 2021–22 school year, however, many states found that fewer teachers returned to their positions than in previous years. Though the recent increases in turnover do not yet rise to a “mass exodus,” it does suggest that we should pay careful attention to the underlying factors driving turnover and increase supports in the future.

What are some of the biggest challenges teachers faced over the recent pandemic school years?

Teachers faced a wide range of challenges during the pandemic, including unexpected shifts in schooling mode, learning new technologies, additional child care responsibilities, and managing personal health concerns. And these challenges were not equally felt by all teachers. For example, younger teachers were more likely to feel burdened by additional childcare responsibilities while older teachers were more likely to report concerns about their personal health.

What are some of the signs of teacher burnout?

There are several signs of teacher burnout.

First, many teachers are reporting high levels of job-related stress. It’s worth noting that teachers also reported high levels of stress prior to the pandemic, but they are now also reporting that the career is not worth the stress.

Second, teachers are increasingly indicating that they are considering leaving their jobs.

Finally, we’re seeing that these thoughts of turnover have materialized: across the country, we’re seeing reports of increased teacher turnover rates in the most recent school year.

Recent studies have pointed to a sharp increase in educational inequity throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for students of color. How can school administrators, educators, and society at-large work to address this gap?

We know that the increase in inequality was not as severe in districts that held more in-person schooling during the pandemic. This suggests that in-person schooling plays an important role in reducing inequality. Therefore, resuming the standard educational model of full-time in-person learning is a first step. However, it’s also more important than ever to support students who lost ground during the pandemic. Many school districts have pushed for personalized tutoring initiatives, but as with any strategy, there are challenges related to scaling these initiatives to serve all the students in need.

On a societal level, how can we better support teachers?

One potential pathway for improving teacher support is to focus on improving teacher working conditions. A recent study shows that teachers in schools with strong communication, targeted professional development, meaningful collaboration with colleagues, fair expectations, and recognition of effort were more likely to maintain their self-reported sense of success during the early stages of the pandemic.

Were there any positives or benefits that came out of pandemic teaching and learning?

Very few people would argue in support of pandemic-era teaching and learning overall. That said, there have been some instances where students have benefitted in some ways. For example, not having in-person schooling has led to decreases in bullying, both in person and online.

Source: Katherine Gianni and Giana Carrozza for Boston University