Using 3D scanning, researchers are peeking under the preserved skin of Tasmanian tiger specimens to reconstruct their growth and development.

Given that only a few specimens remain of the extinct species, dissecting them—even in the name of science—isn’t really an option.

The researchers instead used a technique called non-invasive X-ray micro-CT scanning, which has also been useful for examining Egyptian mummies.

Christy Hipsley, research associate at Museums Victoria and the University of Melbourne, says that before they were hunted to extinction in 1936, it was very popular for museums to collect samples of the Tasmanian tiger, also known as thylacine or Thylacinus cynocephalus.

Once ranging throughout Australia and New Guinea, the Tasmanian tiger disappeared from the mainland around 3,000 years ago, likely because of competition with humans and dingoes. The last known individual died at the Hobart Zoo in 1936.

“Because it was a marsupial, thylacine young developed in the pouch, so adult specimens sometimes still had young in their pouch,” says Hipsley.

She says that a very limited number of pouch young specimens (joeys) were collected and preserved, and these now exist in various museum collections around the world, from Tasmania to Prague.

“Due to the technological limitations at the time the thylacine went extinct, there are only limited details on its growth and development,” Hipsley says.

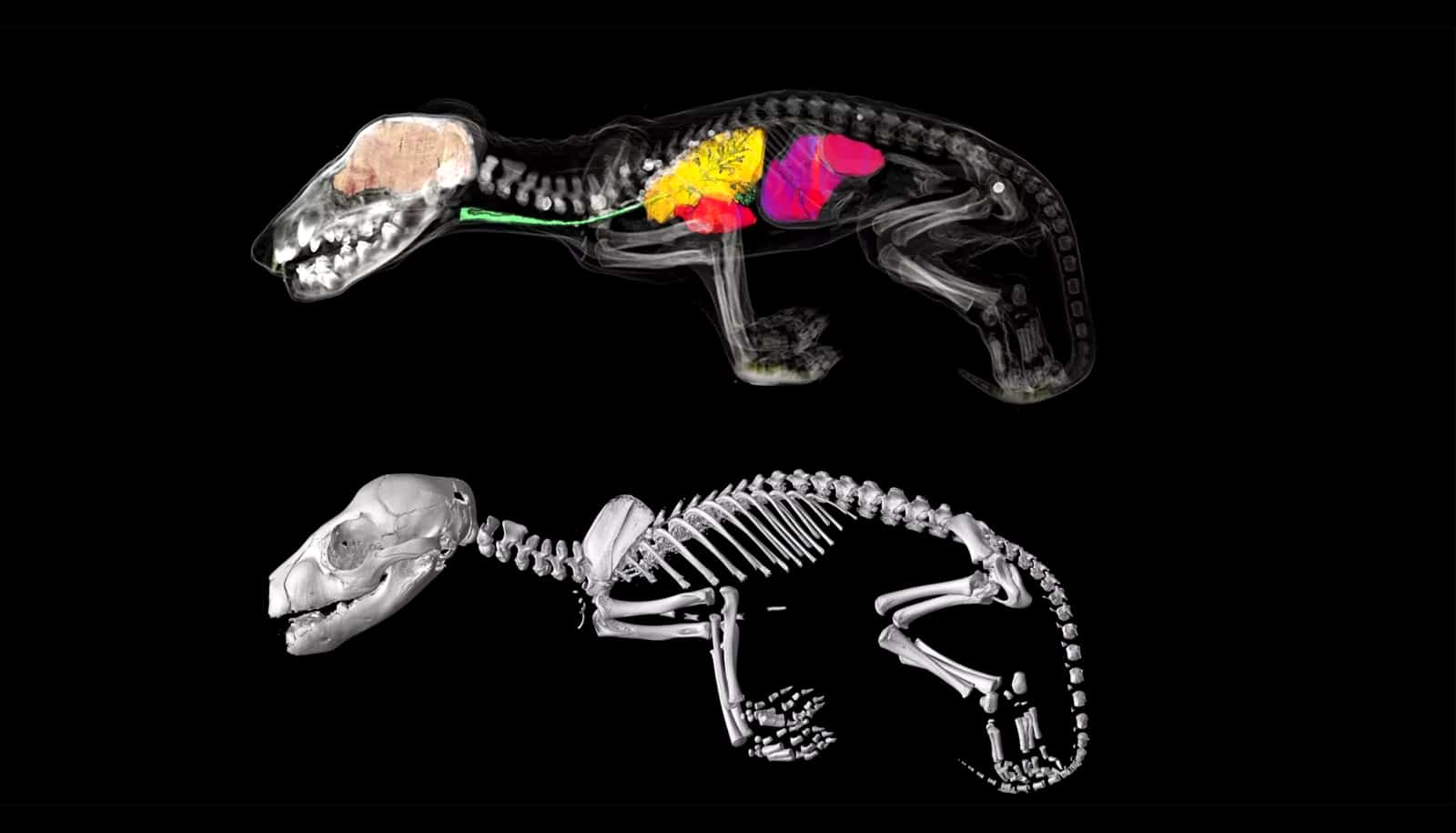

The research team conducted CT scanning on all 13 known pouch young world-wide to create 3D digital models. The models have enabled the team to study their skeletons and internal organs, and reconstruct their growth and development. Their work appears in Royal Society Open Science.

From kangaroo to puppy

Axel Newton, PhD student at the University of Melbourne and lead author of the paper, notes that the collection of joey specimens represents five critical stages of postnatal, or pouch development.

The scans reveal that two specimens in a museum collection weren’t Tasmanian tigers at all.

“Our 3D models have revealed important new information about how this unique extinct marsupial evolved to look so similar to dogs, such as the dingo, despite being very distantly related,” says Newton.

“The digital scans show that when first born the Tasmanian tiger looked like other marsupials like the Tasmanian Devil or the kangaroo.”

These scans show in incredible detail how the Tasmanian tiger started its journey in life as a joey boasting the robust forearms of other marsupials so that it could climb into its mother’s pouch. But by the time it left the pouch around 12 weeks to start independent life, it looked more like a puppy, with longer hindlimbs than forelimbs.

The Tasmanian tiger’s resemblance to the dingo is known as one of the best examples of convergent evolution in mammals. Convergent evolution is when two species, despite not being closely related, evolve to look very similar. The Tasmanian tiger would have last shared a common ancestor with the canids (dogs and wolves) around 160 million years ago.

Hipsley says after sequencing the Tasmanian tiger genome in 2017, this research is one more piece in the puzzle of why they evolved to look so similar to dogs.

Mistaken identity

Andrew Pask, associate professor at the University of Melbourne, explains the scanning was an incredibly effective technique to study the skeletal anatomy of the specimens without causing any damage to them.

“This research clearly demonstrates the power of CT technology. It has allowed us to scan all the known Thylacine joey specimens in the world, and study their internal structures in high resolution without having to dissect or cause damage to the specimen,” Pask says.

“By examining their bone development, we’ve been able to illustrate how the Tasmanian tiger matured, and identify when they took on the appearance of a dog.”

The study has also revealed that two specimens held in the collection of the Tasmanian Museums and Art Gallery (TMAG) weren’t Tasmanian tigers at all. Instead, they are most likely to be quolls or Tasmanian devils, based on the number of vertebrae and presence of large epipubic bones (the specialized bones that support the pouch in modern marsupials).

Scientists sequence Tasmanian tiger genome

Kathryn Medlock, senior curator of vertebrate zoology at TMAG, says the museum has received many requests to dissect its pouch young over the years but have always refused.

“One of the major advantages of this new technology is that it has enabled us to do research and answer many questions without destruction of the sample specimens,” Medlock says.

The 3D digital Tasmanian tiger models are publicly available here as a resource for current and future researchers.

Source: University of Melbourne