Wearable skin sensors that detect what’s in your sweat could one day replace invasive procedures like blood draws and provide real-time updates on dehydration, fatigue, and other health problems.

Researchers used the sensors to monitor the sweat rate, and the electrolytes and metabolites in sweat, from volunteers who were exercising, and others who were experiencing chemically induced perspiration.

“The goal of the project is not just to make the sensors but start to do many subject studies and see what sweat tells us—I always say ‘decoding’ sweat composition,” says senior author Ali Javey, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California, Berkeley.

“For that we need sensors that are reliable, reproducible, and that we can fabricate to scale so that we can put multiple sensors in different spots of the body and put them on many subjects,” says Javey, who is also a faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

High volume, low cost

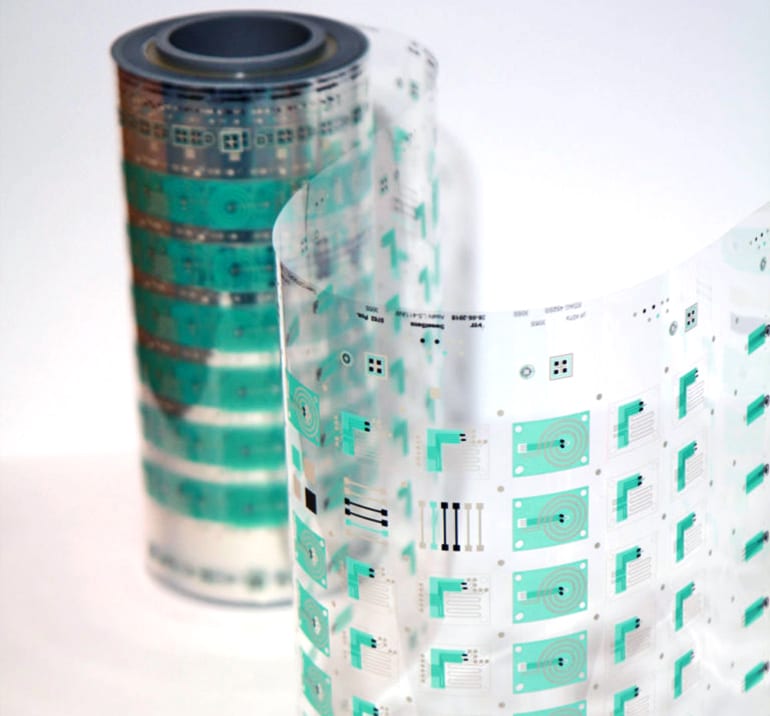

As reported in Science Advances, scientists have developed a “roll-to-roll” processing technique that can quickly print the sensors onto a sheet of plastic like words on a newspaper.

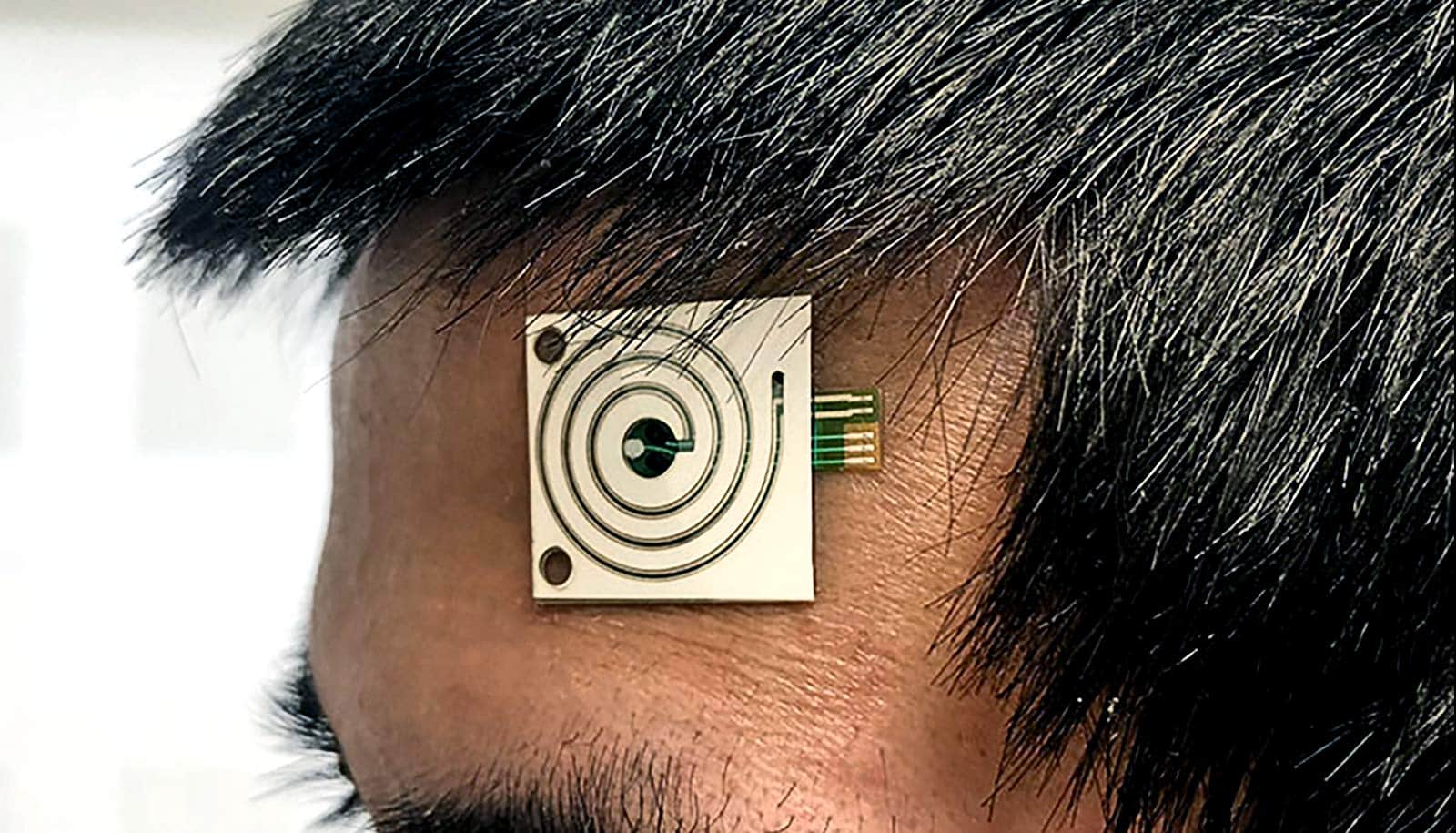

The new sensors contain a spiraling microscopic tube, or microfluidic, that wicks sweat from the skin. By tracking how fast the sweat moves through the microfluidic, the sensors can report how much a person is sweating, or their sweat rate.

The microfluidics are also outfitted with chemical sensors that can detect concentrations of electrolytes like potassium and sodium, and metabolites like glucose.

Javey and his team worked with researchers at the VTT Technical Research Center of Finland to develop a way to quickly manufacture the sensor patches in a roll-to-roll processing technique similar to screen printing.

“Roll-to-roll processing enables high-volume production of disposable patches at low cost,” says Jussi Hiltunen of VTT. “Academic groups gain significant benefit from roll-to-roll technology when the number of test devices is not limiting the research. Additionally, up-scaled fabrication demonstrates the potential to apply the sweat-sensing concept in practical applications.”

Real-time health

To better understand what sweat can say about the real-time health of the human body, the researchers first placed the sweat sensors on different spots on volunteers’ bodies—including the forehead, forearm, underarm, and upper back—and measured sweat rates and the sodium and potassium levels in their sweat while they rode on an exercise bike.

They found that local sweat rate could indicate the body’s overall liquid loss during exercise, meaning that tracking sweat rate might be a way to give athletes a heads up when they may be pushing themselves too hard.

“Traditionally what people have done is they would collect sweat from the body for a certain amount of time and then analyze it,” says Hnin Yin Yin Nyein, a graduate student in materials science and engineering at UC Berkeley and one of the paper’s lead authors.

“So you couldn’t really see the dynamic changes very well with good resolution. Using these wearable devices we can now continuously collect data from different parts of the body, for example to understand how the local sweat loss can estimate whole-body fluid loss.”

Researchers also used the sensors to compare sweat glucose levels and blood glucose levels in healthy and diabetic patients, finding that a single sweat glucose measurement cannot necessarily indicate a person’s blood glucose level.

“There’s been a lot of hope that non-invasive sweat tests could replace blood-based measurements for diagnosing and monitoring diabetes, but we’ve shown that there isn’t a simple, universal correlation between sweat and blood glucose levels,” says Mallika Bariya, a graduate student in materials science and engineering and the paper’s other lead author.

“This is important for the community to know, so that going forward we focus on investigating individualized or multi-parameter correlations.”

Additional coauthors are from the VTT Technical Research Center of Finland and UC Berkeley. NSF Nanomanufacturing Systems for Mobile Computing and Mobile Energy Technologies; the Berkeley Sensor and Actuator Center; and the Bakar fellowship funded the work.

Source: UC Berkeley