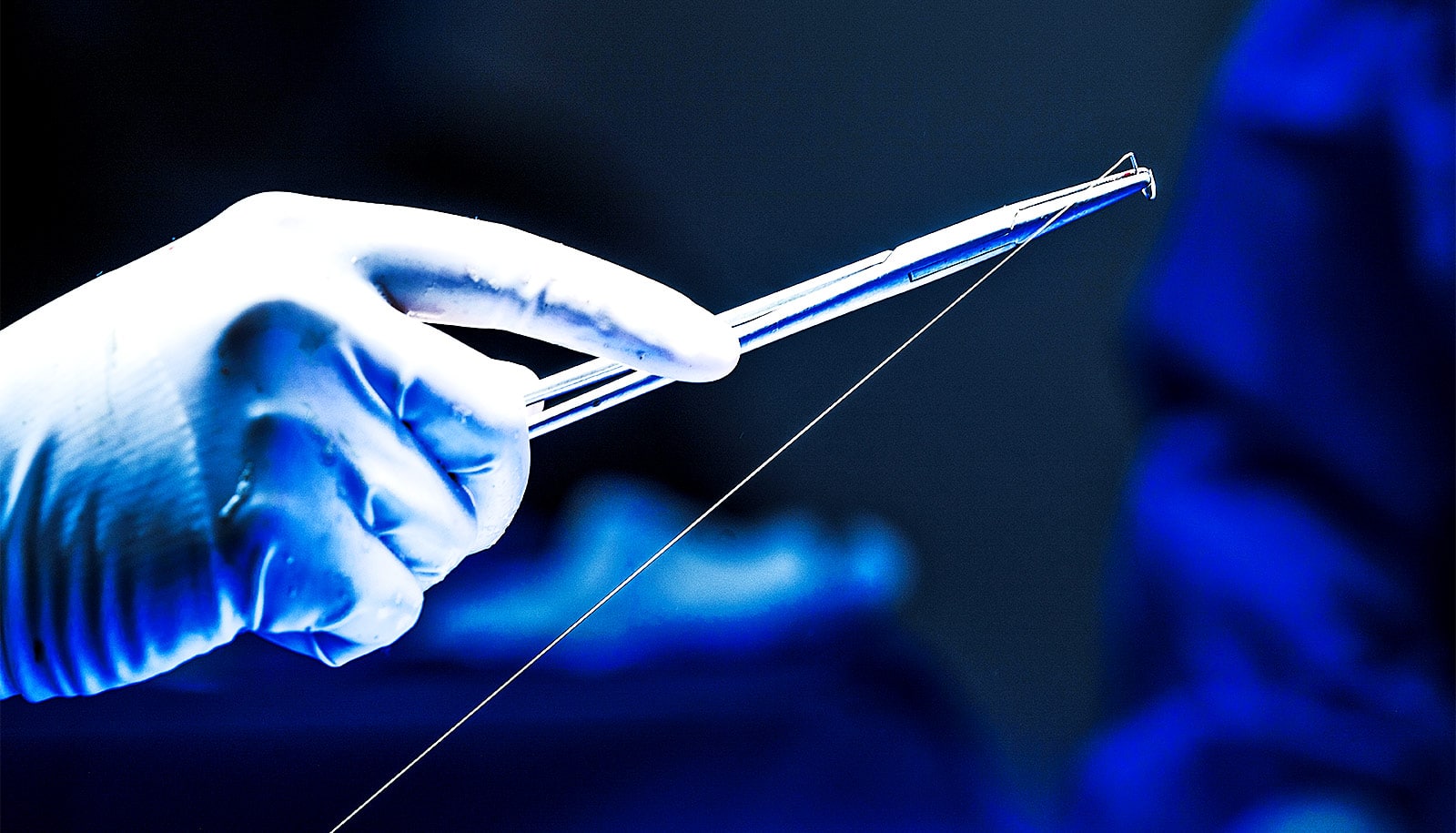

Researchers have developed innovative tough gel sheathed sutures inspired by the human tendon.

The new sutures can deliver drugs, prevent infections, and monitor wounds.

Sutures are used to close wounds and speed up the natural healing process, but they can also complicate matters by causing damage to soft tissues with their stiff fibers.

The next-generation sutures contain a slippery, yet tough gel envelop, imitating the structure of soft connective tissues. In putting the tough gel sheathed (TGS) sutures to the test, the researchers found that the nearly frictionless gel surface mitigated the damage traditional sutures typically cause.

Conventional sutures have been around for centuries and are used to hold wounds together until the healing process is complete. But they are far from ideal for tissue repair. The rough fibers can slice and damage already fragile tissues, leading to discomfort and post-surgery complications.

Part of the problem lies in the mismatch between our soft tissues and the rigid sutures that rub against contacting tissue, say the researchers.

To tackle the problem, the team developed a new technology that mimics the mechanics of tendons.

“Our design is inspired by the human body, the endotenon sheath, which is both tough and strong due to its double-network structure. It binds collagen fibers together while its elastin network strengthens it,” says lead study author Zhenwei Ma, a PhD student under the supervision of Jianyu Li, an assistant professor in the mechanical engineering department at McGill University.

The endotenon sheath not only forms a slippery surface to reduce friction with surrounding tissues in joints, but it also delivers necessary materials for tissue repair in a tendon injury. In the same way, TGS sutures can be engineered to provide personalized medicine based on a patient’s needs, say the researchers.

“This technology provides a versatile tool for advanced wound management. We believe it could be used to deliver drugs, prevent infections, or even monitor wounds with near-infrared imaging,” says Li.

“The ability to monitor wounds locally and adjust the treatment strategy for better healing is an exciting direction to explore,” says Li, who is also a chair in biomaterials and musculoskeletal health.

The research appears in Science Advances.

Source: McGill University