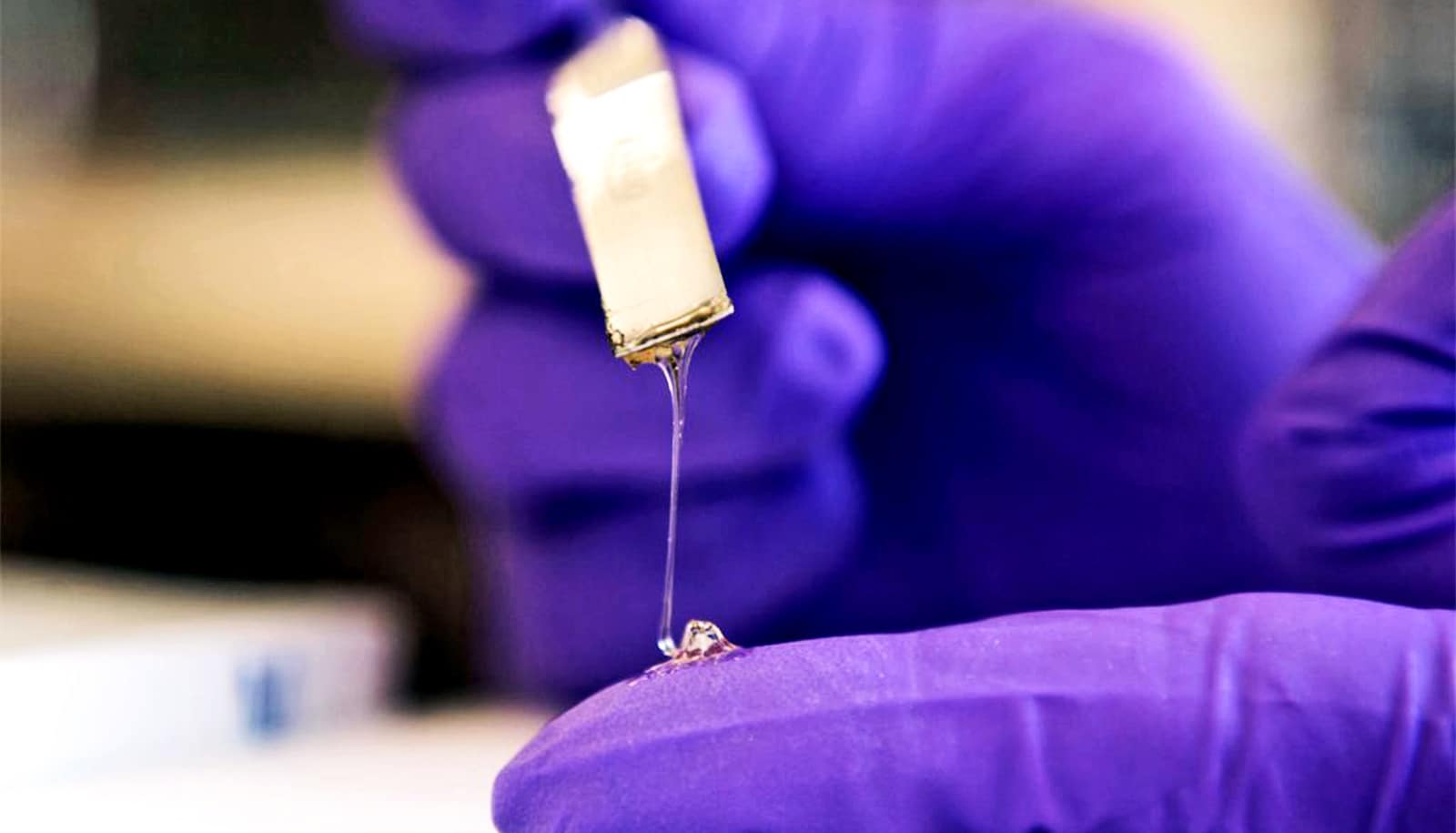

Researchers have created a new adhesive with sticking power, but not staying power.

It’s a biodegradable material made of entirely naturally derived chemical components that break down after use.

One particularly important job that plastics perform every day is to make things adhere to a variety of surfaces—like the way sticky parts work on Post-it notes, Scotch tape, or even Band-Aids.

Researchers working to find eco-friendly alternatives to plastics set out to design an adhesive with sticking power but not staying power—a biodegradable material made of entirely naturally derived chemical components that break down after use.

“We are replacing current materials that are not degradable with something better for the environment while still maintaining the properties we expect from a performance standpoint,” says Mark Grinstaff, a professor of translational research at the College of Engineering, a professor of chemistry, and director of the Grinstaff Group at Boston University. “We can have both, we just have to be smart about how we do it.”

Adhesive alternatives

The team says their new adhesive’s formula easily adapts to suit a wide range of industrial and medical applications that benefit from sticky materials.

“We wanted to mimic the plastic binders in paints that make them stick to the wall,” explains Anjeza Beharaj, who earned her PhD in organic chemistry while working in Grinstaff’s lab, which works primarily with polymers, large molecular structures made up of chemically linked materials.

“…what’s exciting is that this material repurposes carbon dioxide that would otherwise go into the atmosphere…”

Although polymers are often thought to be synonymous with plastic, they can also be made of naturally derived materials—even our DNA is considered a polymer. Beharaj and Grinstaff worked with undergraduate researcher Ethan McCaslin and William A. Blessing, who recently earned a PhD in chemistry, to develop an adhesive system made of biodegradable polymers. The adhesive can effectively stick to anything just as well as, if not better than, plastic-based products on the market today.

“The key ingredient is carbon dioxide,” Beharaj explains. About 20 to 40% of the biodegradable adhesive, which has the consistency of honey or molasses, is composed of CO2.

“We tend to think of carbon as a polluting gas in the atmosphere, and it can be, in excessive amounts. But what’s exciting is that this material repurposes carbon dioxide that would otherwise go into the atmosphere, and there’s a potential for oil refineries and production plants to repurpose the gas for environmentally friendly polymers. So it’s a win for the environment and a win for the consumer, as it can potentially lower the price of goods since CO2 is a cheap raw material,” she says.

Way more sustainable

The researchers estimate that their adhesive will take a year or less to fully break down in the environment, unlike plastic which will pollute landfills for hundreds of years. (Consider for a moment that every Band-Aid and piece of duct tape you’ve ever thrown away is still sitting in a garbage pile somewhere!)

“This represents good progress toward making products greener, which should be a priority for the scientific community right now,” says McCaslin. He’s hopeful that the adhesive will “inspire more researchers to work toward a similar goal of making products more eco-friendly,” he says.

Grinstaff’s team envisions the biodegradable adhesive solution could be tailored to fit the many needs of today’s plastic adhesives. By adjusting the ratio of polymers and CO2 in each batch of adhesives, they are able to make the material’s adhesion stronger, weaker, or able to respond to certain kinds of surfaces. The adhesive strength can range from that of Scotch tape to permanent wood glue, and it can be tailored to stick to metal, glass, wood, Teflon, and even wet surfaces.

The naturally derived and biodegradable materials are also completely safe to use on or in the human body, according to Beharaj. The adhesives could potentially replace metal used in surgeries to hold bone together, making some surgical procedures less invasive. They could also be used on the surface of skin to protect cuts, scrapes, wounds, or post-surgical incisions.

With such a huge array of possibilities, the next step is to find the best way to use and market the adhesives.

“The question right now is finding the best application, and we’ll start by learning what the needs are from different communities,” says Grinstaff. “People in the surgical field will have a different idea than someone in packaging, but we can address both markets.”

A paper on the adhesive appears in Nature Communication. Support for the work came, in part, from the National Science Foundation.

Source: Boston University