A new surgical patch with a sensor function can seal wounds in the abdomen and send a warning before the occurrence of dangerous leaks on sutures in the gastrointestinal tract.

After surgery on the stomach or intestines, leaks in sutures may cause the contents of the digestive tract to seep into the abdomen. “Even today, such leaks are a life-threatening complication,” says Inge Herrmann, professor of nanoparticular systems at ETH Zurich and a researcher at Empa in St. Gallen.

The idea of sealing sutured tissue in the abdominal cavity with a plaster has already arrived in operating rooms. But the patches, made of protein-containing material, dissolve too quickly when they come into contact with digestive juices. Researchers have therefore looked for new solutions.

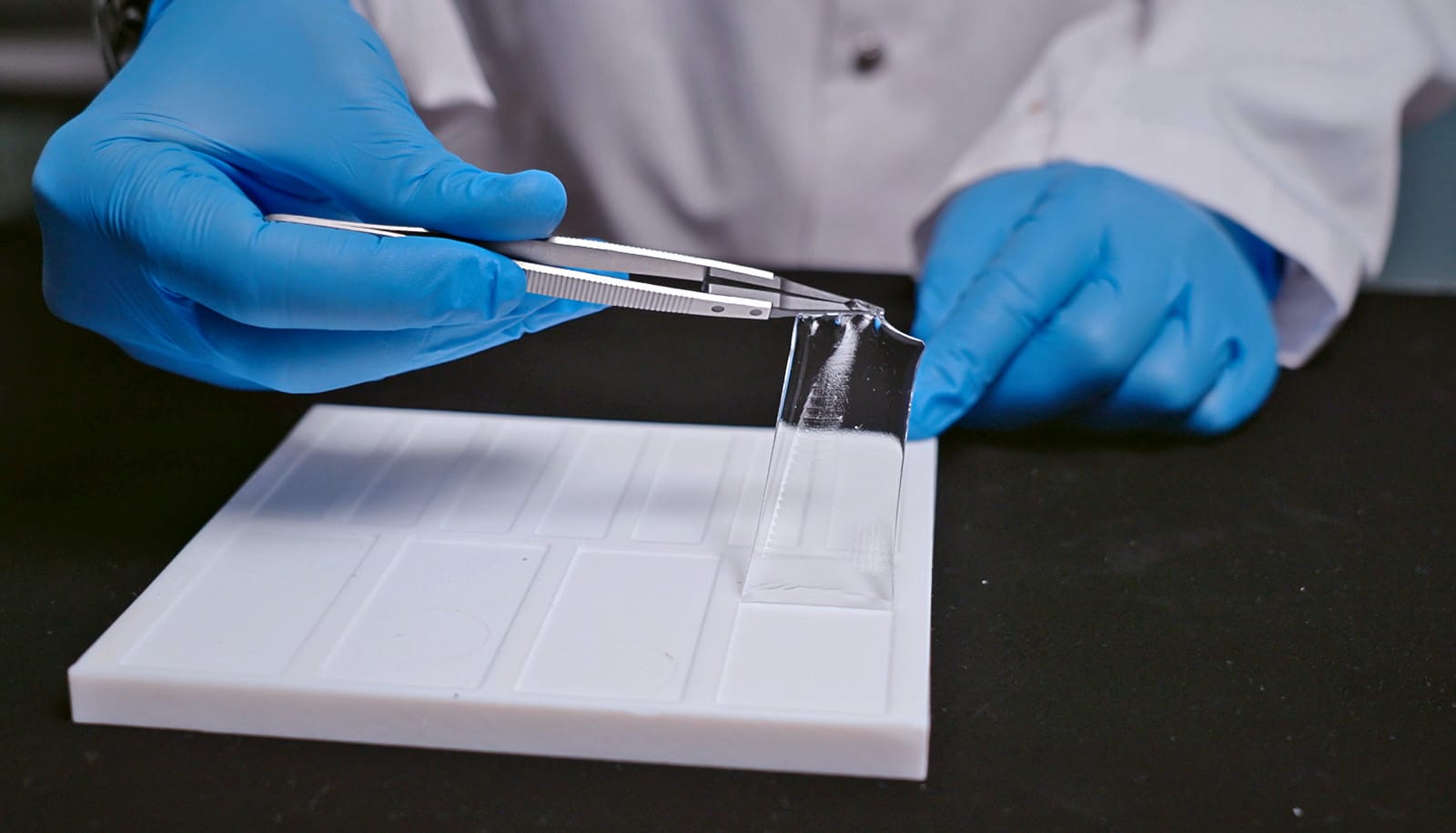

Over the past few years, the scientists have developed a plaster made of polymers that form a hydrogel that can absorb fluid. The polymers cross-link with the intestinal tissue and seal the wound. In this way, the patch prevents the acidic digestive juices and germ-laden food residues from escaping from the digestive tract and triggering peritonitis or even life-threatening blood poisoning.

Now the researchers have gone one step further.

“Surgeons have told us that they keep a close eye on the surgical field during even the most complicated procedures—but as soon as the abdominal cavity is closed, they are ‘blind’ and may not notice leaks until it is too late,” says Alexandre Anthis, a postdoc in Herrmann’s group and co-developer of the patch.

The researchers have equipped their surgical patch with non-electronic sensors that already indicate before digestive juices can leak into the abdominal cavity. The sensors are protein structures or salts incorporated into the patch that react either to changes in pH caused by escaping gastric acid or to certain enzymes present in the intestine. When the sensor elements come into contact with digestive juices, their structure changes, which doctors can detect from outside the body using biomedical imaging.

As reported in the journal Advanced Science, the researchers equipped the sensor elements in such a way that their reaction can also be detected by computer tomography (CT). This was possible because, thanks to a combination of reactive salts and insoluble tantalum oxide, the scientists were able to shape the sensor elements in a way that is conspicuous in computed CT.

“On contact with digestive fluid, for example, the sensor changes its shape from a filled round area to a ring,” says first author Benjamin Suter, a doctoral student in Herrmann’s group.

The researchers already developed the sensor elements in a paper published last year, at that time still without a shape-changing function. Moreover, at that time it was not yet possible to detect the structural change in the plaster after a sensor reaction with CT, but only with ultrasound imaging. Now the change can be seen with both imaging techniques.

“In future, a sensor whose shape clearly stands out from anatomical structures in CT and ultrasound images, could reduce ambiguity of impending leak diagnostics,” says Herrmann.

The intestinal patch could thus not only reduce the risk of complications after abdominal surgery, but also shorten hospital stays and save healthcare costs.

“The intestinal patch project is already attracting a great deal of interest from the medical profession,” Herrmann says.

Source: ETH Zurich