Researchers have discovered bacteria and fungi on a range of surgical implants—including the screws that fix broken bones and hip replacements—inside patients.

“We have always believed implants to be completely sterile.”

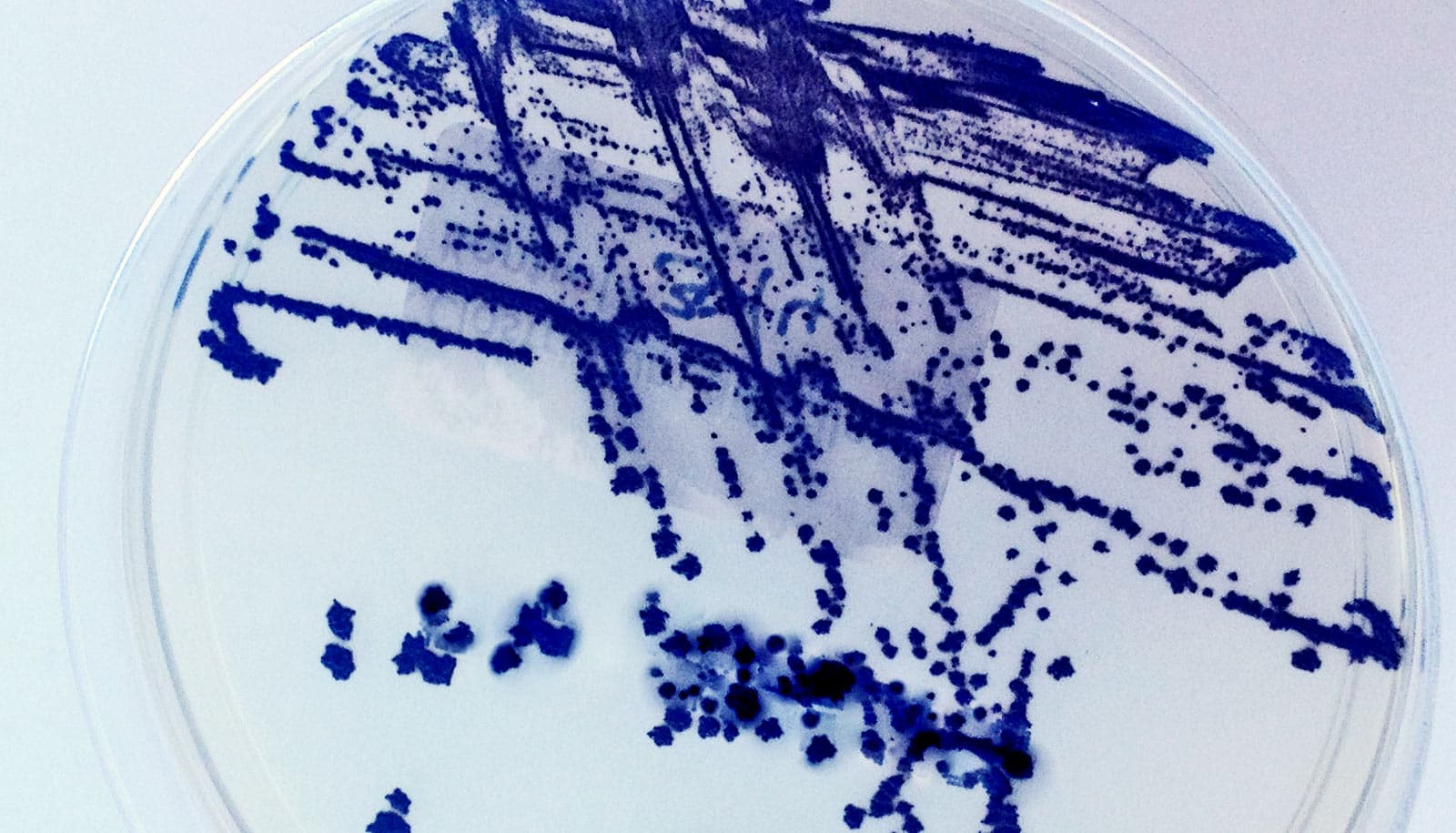

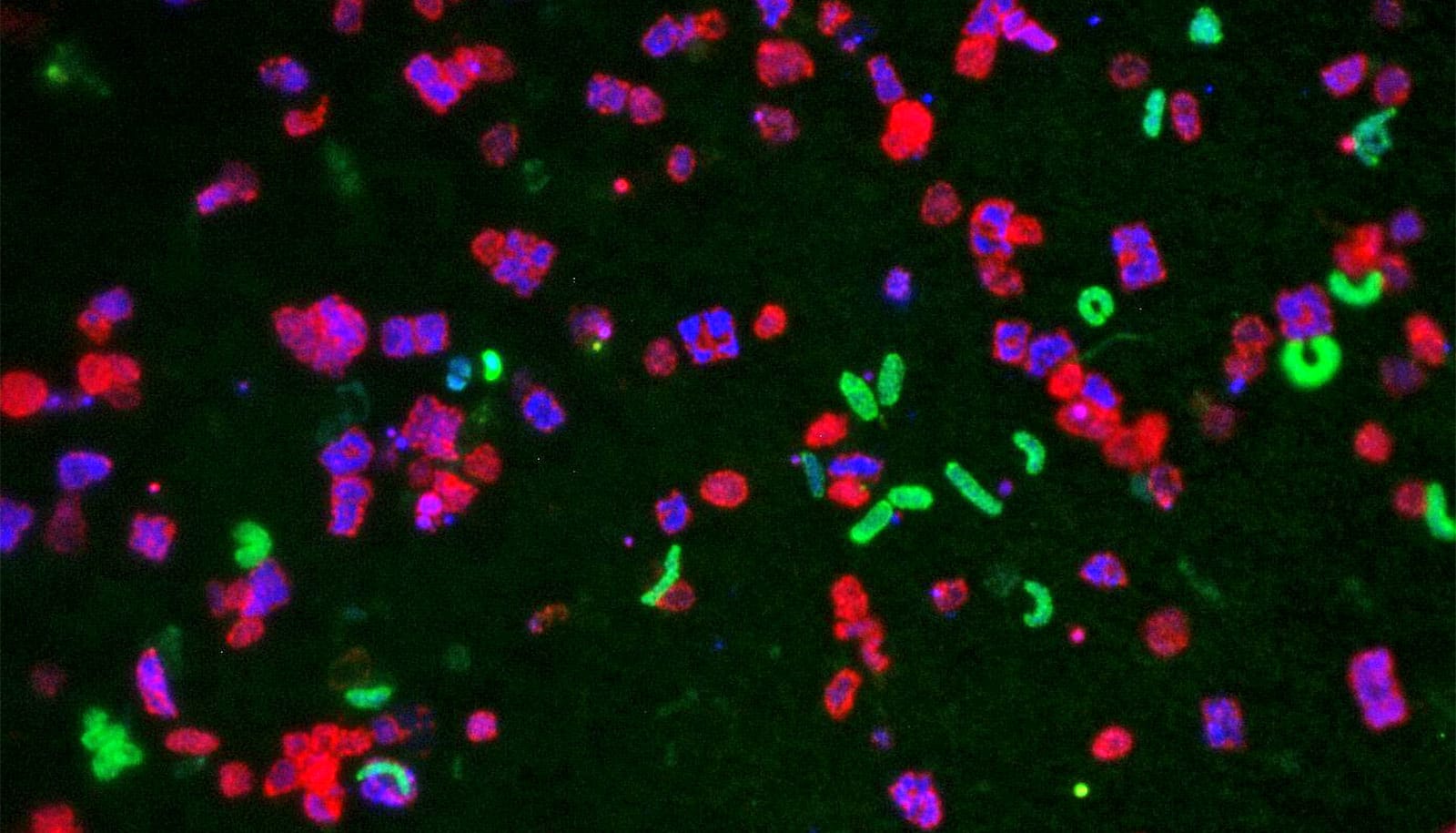

The researchers examined 106 implants and the surrounding tissue from different patient groups. They discovered that bacteria, fungi, or both had colonized more than 70 percent—corresponding to 78 implants. None of the patients with implants showed signs of infection, though.

“This opens up a brand new field and understanding of the interplay between the body and bacteria and microbiomes. We have always believed implants to be completely sterile. It is easy to imagine, though, that when you insert a foreign body into the body, you create a new niche, a new habitat for bacteria.

“Now the question is whether this is beneficial, like the rest of our microbiome, whether they are precursors to infection or whether it is insignificant,” says study coauthor Thomas Bjarnsholt, a professor in the immunology and microbiology department at the University of Copenhagen.

Don’t freak out

The researchers studied implants ranging from screws and knees to pacemakers, which they collected at five different hospitals in the Capital Region of Denmark. The implants came from four different patient groups: patients with aseptic loosening, craniofacial implants, healed fractures, and recently diseased who had implants.

“It is important to stress that we have found no direct pathogens, which normally cause infection.”

Of the examined implants, bacteria had colonized a significant majority of screws, while the opposite was the case for knees. The prevalence of fungi was the same for the different types of implants. Common to all cases, however, was that none of the discovered bacteria or fungi were pathogens such as staphylococcus.

“It is important to stress that we have found no direct pathogens, which normally cause infection. Of course if they had been present, we would also have found an infection,” says study coauthor Tim Holm Jakobsen, assistant professor in the immunology and microbiology department.

“The study shows a prevalence of bacteria in places where we do not expect to find any. And they manage to remain there for a very long time probably without affecting the patient negatively. In general, you can say that when something is implanted in the body it simply increases the likelihood of bacteria development and the creation of a new environment,” says Jakobsen.

Sterile before, but not after

The researchers also conducted 39 controls to examine and ensure that the process of collecting samples or the subsequent analysis had not contaminated the implants. They did this by opening a sterile implant, a screw, for example, in the laboratory, during surgery or implanted in a patient and removing it again shortly after.

All controls were negative, which means that none of them led to the discovery of bacteria or fungi. According to the researchers, this must mean that the colonization of bacteria and fungi begins after the implant is inserted into the body. On average, the examined implants had been in the body of the patient for 13 months.

Coat implants with zinc oxide for fewer infections

“If our discovery of bacteria and fungi was simply a result of contamination, we would have reached the same results by inserting an implant in a patient and removing it again. But all the controls were negative. So it is something that develops inside the body over a period of time,” Bjarnsholt explains.

The next step for the researchers is to examine the effect of the identified bacteria and fungi on the body and the implant and precisely how they emerge.

The study appears in the journal APMIS.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen, Bispebjerg Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Herlev Hospital, and the University of Texas contributed to the work. The Lundbeck Foundation and Region Hovedstadens Udviklingsfond funded the study.

Source: University of Copenhagen