Friday the 13th is here and those with “triskaidekaphobia” (fear of the number 13) may be especially on edge.

And on Saturday the 14th—a big college football day—fans of all flavors around the country will be pulling on their special socks, donning their lucky jerseys, and exercising countless gestures, gimmicks, and gambits to inspire their team.

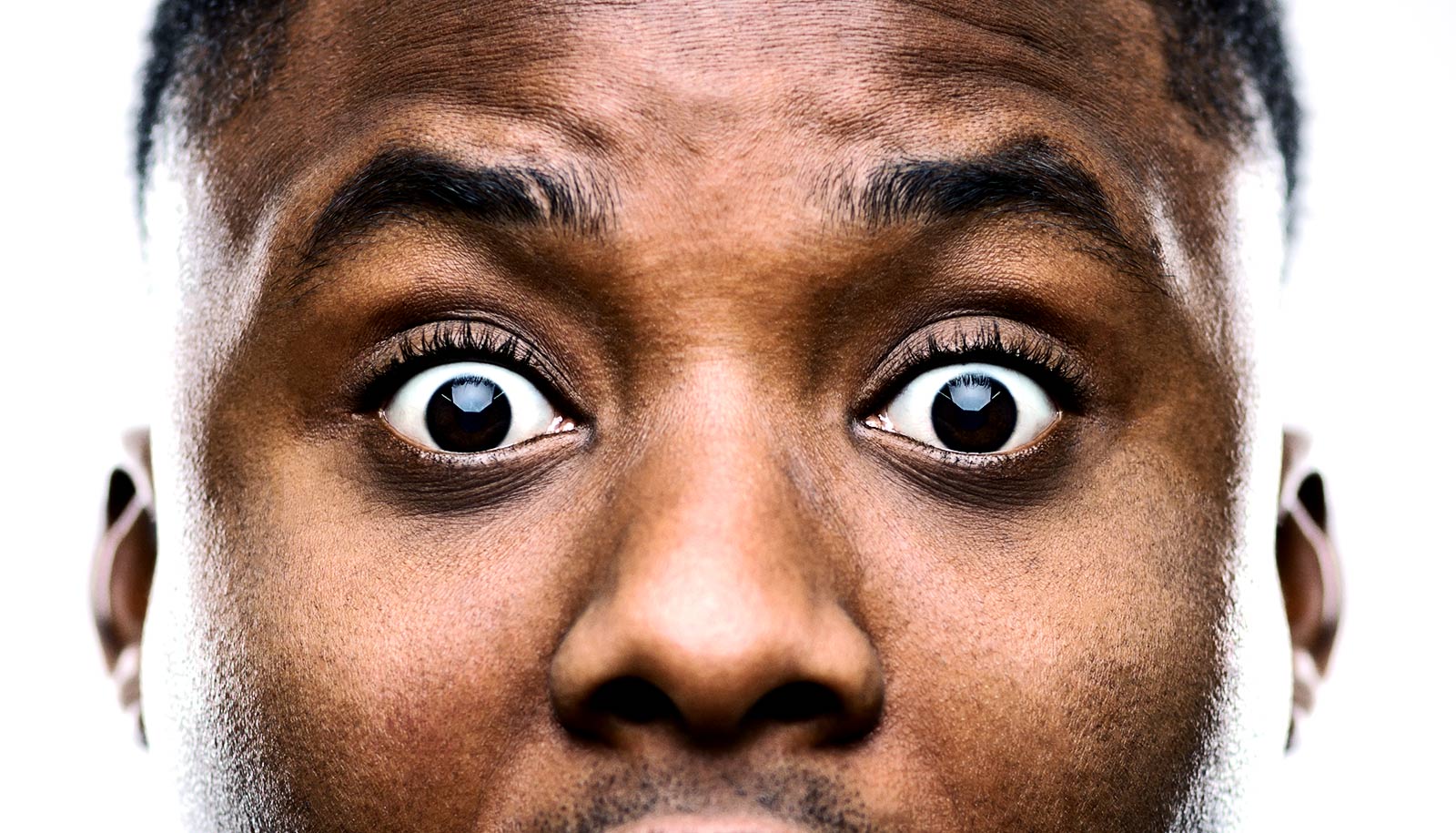

“We may joke about our superstitions, but they are pervasive and powerful.”

“Superstitions come in all shapes and sizes,” notes David Kling, a professor in the University of Miami religious studies department.

“In sports, baseball rituals are rife; or consider that Michael Jordan wore his UNC shorts under NBA shorts for his entire career; or consider that hockey players refuse to shave during playoffs—at least as long as their team is winning.

“In other areas of life, superstitions are present even though people don’t like to admit to being superstitious, and in fact they may even be averse to the idea that they have supernatural beliefs,” adds Kling.

Superstitions are, by definition, an irrational abject attitude of mind—a belief, action, or practice that has no basis in fact yet is treated as legitimate conduct. Yet nearly all of us have them.

Kling points out that lab experiments have found considerable evidence for superstitious and supernatural thinking, even among self-declared atheists.

“In one experiment, regular people tended to believe that they had influence over events even when it was impossible—believing that they helped a player score in a basketball game by willing the result or that they had harmed someone by sticking pins in a voodoo doll,” he says.

Research indicates that people are more likely to display superstitious behavior under four conditions: high stakes, uncertainty, lack of control, and stress or anxiety, Kling says.

And a key element of superstition is the expectation of supernatural consequences of one’s actions. Call it karma, a cosmic force, God balancing the scales of justice—the idea is that our lives are being watched by forces beyond us.

“Which, according to cognitive scientists of religion, is a feature of human nature found in all people—religious believers, agnostics, and atheists,” says Kling, a specialist in American religious history.

“In short, superstitious beliefs and behaviors are all aimed at managing supernatural reward and punishment. All are attempts to exert control over events.”

From a belief standpoint, most people “know” that their superstitious practice offers no true value, yet they still do it. Why?

Kling offered the example of Niels Bohr, the Nobel laureate and physicist. An American scientist visited Bohr at his home in Denmark and noticed a horseshoe hanging over Bohr’s desk.

“Surely,” the scientist remarked, “you don’t believe that the horseshoe will bring you good luck. After all, you’re a scientist.” Bohr responded: “I believe no such thing… I am scarcely likely to believe in such foolish nonsense. However, I am told that a horseshoe will bring you good luck whether you believe it or not.”

“We may joke about our superstitions, but they are pervasive and powerful,” Kling says.

Catherine Newell, an associate professor in the religious studies department, suggests that modern science and superstitions run into each other at the notion of “falsifiability.”

Newell, a scholar of the conjoined histories of religion and science, notes that during the 20th century, several philosophers and historians set out to define what science is, mostly by illustrating what it is not. Of the epistemological queries and philosophical definitions, arguably the most famous was put forth by philosopher of science Karl Popper who attempted to draw a hard line between real science and its facsimile in the form of falsification.

“Popper was not so much interested in a concrete definition of science as he was in distinguishing science from pseudoscience,” Newell explains.

“Popper was stuck on the problem of demarcation: What can we definitively say is science, what can we identify as pseudoscience, and how can we tell the difference?”

By Popper’s standards, the true test of a scientific theory was whether the conclusions reached by the application of the scientific method to a question could be proven wrong, Newell notes.

“So as far as science versus superstition goes, one of the boundary issues is whether a specific action or belief can be falsified,” Newell says.

“Because even though we might feel like it made a difference, there’s just no way to know if wearing your lucky orange-and-green socks or rubbing the belly of your favorite Sebastian stuffy before the [University of Miami-University of Florida] game is the reason we won or not.”

Source: University of Miami