The lucky snapshots of an amateur astronomer in Argentina have given scientists their first view of the initial burst of light from the explosion of a massive star.

During tests of a new camera, Víctor Buso captured images of a distant galaxy before and after the supernova’s “shock breakout”—when a supersonic pressure wave from the exploding core of the star hits and heats gas at the star’s surface to a very high temperature, causing it to emit light and rapidly brighten.

To date, no one has been able to capture the “first optical light” from a normal supernova—that is, one not associated with a gamma-ray or x-ray burst—since stars explode seemingly at random in the sky, and the light from shock breakout is fleeting. The new data provide important clues to the physical structure of the star just before its catastrophic demise and to the nature of the explosion itself.

“Professional astronomers have long been searching for such an event,” says astronomer Alex Filippenko of the University of California, Berkeley, who followed up the discovery with observations at the Lick and Keck observatories that proved critical to a detailed analysis of the explosion, called SN 2016gkg. “Observations of stars in the first moments they begin exploding provide information that cannot be directly obtained in any other way.”

“Buso’s data are exceptional,” he adds. “This is an outstanding example of a partnership between amateur and professional astronomers.”

The discovery and results of follow-up observations from around the world appear in Nature.

1 in 10 million? 1 in 100 million?

On September 20, 2016, Buso, of Rosario, Argentina, was testing a new camera on his 16-inch telescope by taking a series of short-exposure photographs of the spiral galaxy NGC 613, which is about 80 million light years from Earth and located within the southern constellation Sculptor.

Luckily, he examined these images immediately and noticed a faint point of light quickly brightening near the end of a spiral arm that was not visible in his first set of images.

Amateur astronomers spot ‘yellowballs’ in space

Astronomer Melina Bersten and her colleagues at the Instituto de Astrofísica de La Plata in Argentina soon learned of the serendipitous discovery and realized that Buso had caught a rare event, part of the first hour after light emerges from a massive exploding star. She estimated Buso’s chances of such a discovery, his first supernova, at one in 10 million or perhaps even as low as one in 100 million.

“It’s like winning the cosmic lottery,” says Filippenko.

Star slimmed down fast

Bersten immediately contacted an international group of astronomers to help conduct additional frequent observations of SN 2016gkg over the next two months, revealing more about the type of star that exploded and the nature of the explosion.

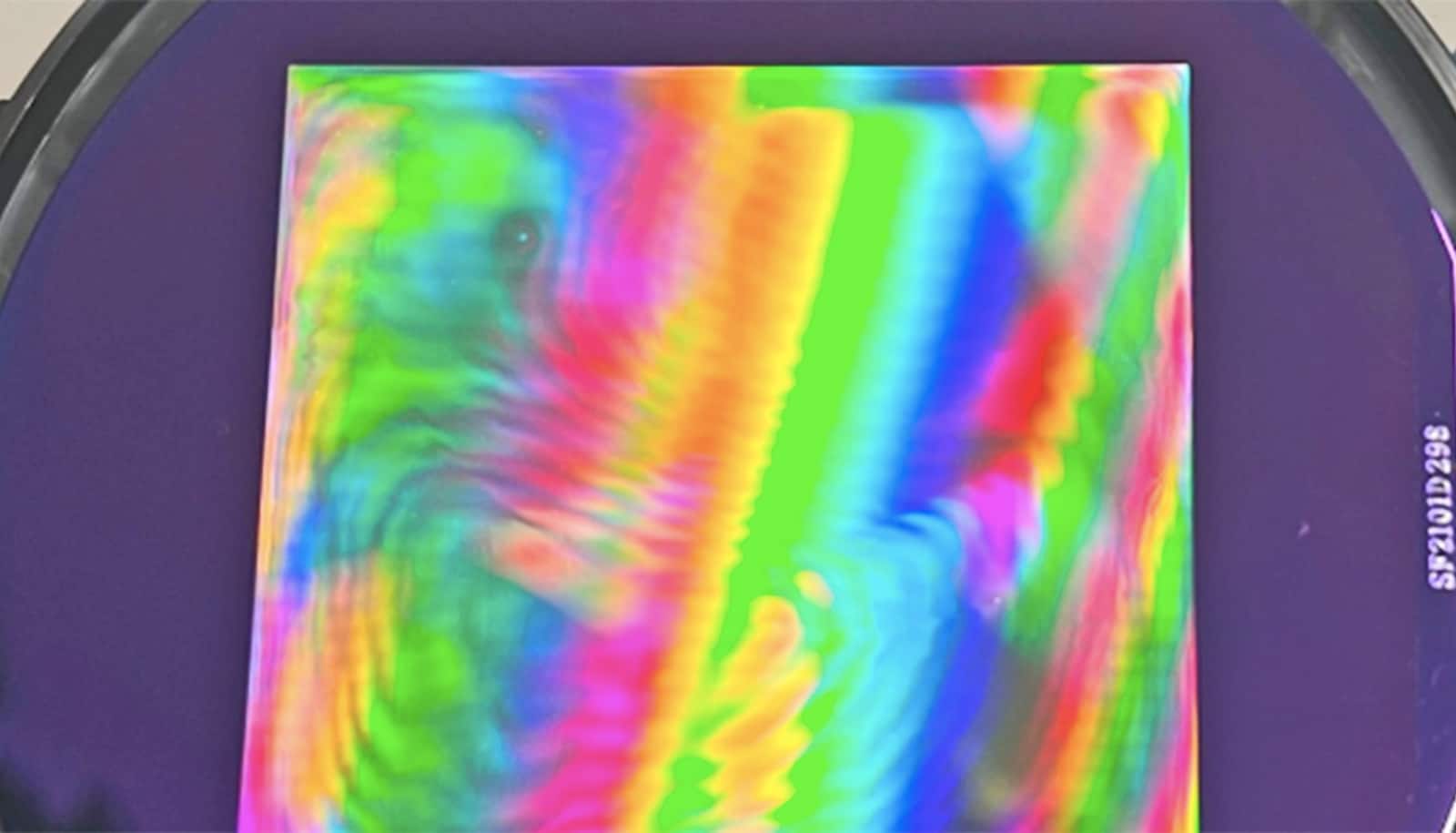

Filippenko and his colleagues obtained a series of seven spectra, where the light is broken up into its component colors, as in a rainbow, with the Shane 3-meter telescope at the University of California’s Lick Observatory near San Jose, California, and with the twin 10-meter telescopes of the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaii. This allowed the international team to determine that the explosion was a Type IIb supernova: the explosion of a massive star that had previously lost most of its hydrogen envelope, a species of exploding star first Filippenko first observationally identified in 1987.

You could find Planet 9 in these ‘flipbook’ movies

Combining the data with theoretical models, the team estimated that the initial mass of the star was about 20 times the mass of our sun, though it lost most of its mass, probably to a companion star, and slimmed down to about 5 solar masses prior to exploding.

Filippenko’s team continued to monitor the supernova’s changing brightness over two months with other Lick telescopes: the 0.76-meter Katzman Automatic Imaging Telescope and the 1-meter Nickel telescope.

“The Lick spectra, obtained with just a 3-meter telescope, are of outstanding quality in part because of a recent major upgrade to the Kast spectrograph, made possible by the Heising-Simons Foundation as well as William and Marina Kast,” Filippenko says.

Support for Filippenko’s group comes from the Christopher R. Redlich Fund, Gary and Cynthia Bengier, the TABASGO Foundation, the Sylvia and Jim Katzman Foundation, many individual donors, the Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science, and NASA through the Space Telescope Science Institute. Research at Lick Observatory receives partial support from Google. The W. M. Keck Observatory operates as a scientific partnership among the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and NASA; the observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the W. M. Keck Foundation.

Source: UC Berkeley