Astronomers have identified a type of companion star that made its partner in a binary system, a carbon-oxygen white dwarf star, explode.

Through repeated observations of SN 2015cp, a supernova 545 million light years away, researchers detected hydrogen-rich debris that the companion star shed prior to the explosion.

Many stars explode as luminous supernovae when, swollen with age, they run out of fuel for nuclear fusion. But some stars can go supernova simply because they have a close and pesky companion star that, one day, perturbs its partner so much that it explodes.

These latter events can happen in binary star systems, where two stars attempt to share dominion. While the exploding star gives off lots of evidence about its identity, astronomers must engage in detective work to learn about the errant companion that triggered the explosion.

“The presence of debris means that the companion was either a red giant star or similar star that, prior to making its companion go supernova, had shed large amounts of material,” says Melissa Graham, an astronomer from the University of Washington.

The supernova material smacked into this stellar litter at 10 percent the speed of light, causing it to glow with ultraviolet light that the Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories detected nearly two years after the initial explosion. By looking for evidence of debris impacts months or years after a supernova in a binary star system, the team believes that astronomers could determine whether the companion had been a messy red giant or a relatively neat and tidy star.

‘Cosmic lighthouses’

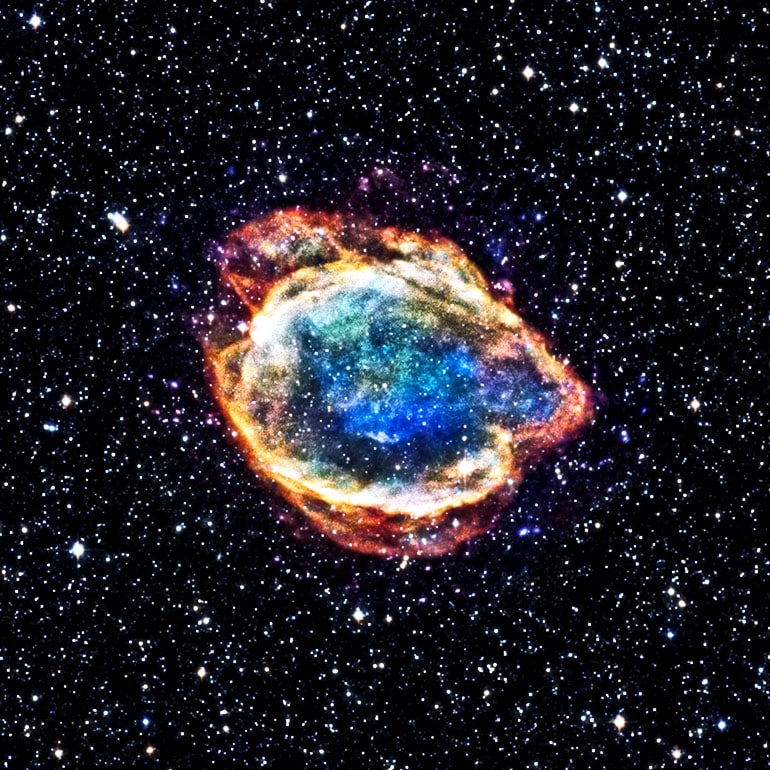

The discovery is part of a wider study of a particular type of supernova known as a Type Ia supernova. These occur when a carbon-oxygen white dwarf star explodes suddenly due to activity of a binary companion. Carbon-oxygen white dwarfs are small, dense and—for stars—quite stable. They form from the collapsed cores of larger stars and, if left undisturbed, can persist for billions of years.

Astronomers have used Type Ia supernovae for cosmological studies because their consistent luminosity makes them ideal “cosmic lighthouses,” Graham says. They’ve been used to estimate the expansion rate of the universe and served as indirect evidence for the existence of dark energy.

Yet scientists are not certain what kinds of companion stars could trigger a Type Ia event. Plenty of evidence indicates that, for most Type Ia supernovae, the companion was likely another carbon-oxygen white dwarf, which would leave no hydrogen-rich debris in the aftermath. Yet theoretical models have shown that stars like red giants could also trigger a Type Ia supernova, which could leave hydrogen-rich debris that would be hit by the explosion.

Out of the thousands of Type Ia supernovae studied to date, researchers later observed only a small fraction impacting hydrogen-rich material shed by a companion star. Prior observations of at least two Type Ia supernovae detected glowing debris months after the explosion. But scientists weren’t sure if those events were isolated occurrences, or signs that Type Ia supernovae could have many different kinds of companion stars.

“All of the science to date that has been done using Type Ia supernovae, including research on dark energy and the expansion of the universe, rests on the assumption that we know reasonably well what these ‘cosmic lighthouses’ are and how they work,” says Graham. “It is very important to understand how these events are triggered, and whether only a subset of Type Ia events should be used for certain cosmology studies.”

Peering into space

The team used Hubble Space Telescope observations to look for ultraviolet emissions from 70 Type Ia supernovae approximately one to three years following the initial explosion.

“By looking years after the initial event, we were searching for signs of shocked material that contained hydrogen, which would indicate that the companion was something other than another carbon-oxygen white dwarf,” says Graham.

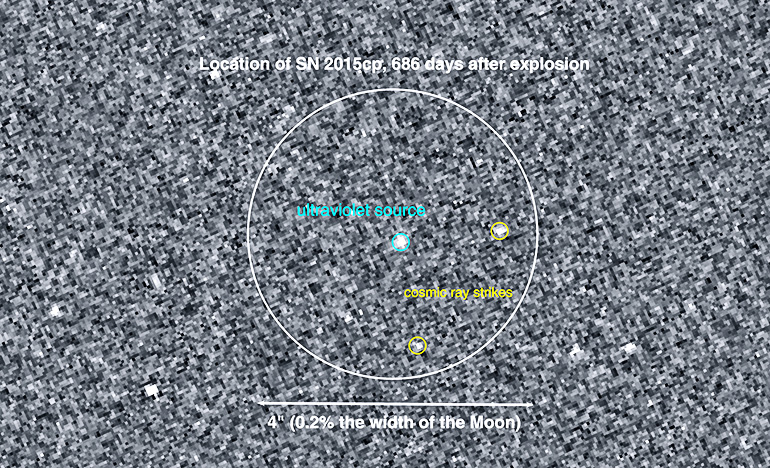

In the case of SN 2015cp, a supernova astronomers first detected in 2015, the scientists found what they were searching for. In 2017, 686 days after the supernova exploded, Hubble picked up an ultraviolet glow of debris. This debris was far from the supernova source—at least 100 billion kilometers, or 62 billion miles, away. For reference, Pluto’s orbit takes it a maximum of 7.4 billion kilometers from our sun.

By comparing SN 2015cp to the other Type Ia supernovae in their survey, the researchers estimate that no more than 6 percent of Type Ia supernovae have such a litterbug companion. Repeated, detailed observations of other Type Ia events would help cement these estimates, Graham says.

The Hubble Space Telescope was essential for detecting the ultraviolet signature of the companion star’s debris for SN 2015cp. In the fall of 2017, the researchers arranged for additional observations of SN 2015cp by the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in New Mexico, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, and NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, among others. These data proved crucial in confirming the presence of hydrogen. Chelsea Harris, a research associate at Michigan State University, presented the findings in a paper.

“The discovery and follow-up of SN 2015cp’s emission really demonstrates how it takes many astronomers, and a wide variety of types of telescopes, working together to understand transient cosmic phenomena,” says Graham. “It is also a perfect example of the role of serendipity in astronomical studies: If Hubble had looked at SN 2015cp just a month or two later, we wouldn’t have seen anything.”

Graham is also a science analyst with the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, or LSST.

“In the future, as a part of its regularly scheduled observations, the LSST will automatically detect optical emissions similar to SN 2015cp—from hydrogen impacted by material from Type Ia supernovae,” says Graham. “It’s going to make my job so much easier!”

The researchers shared their work at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle and the paper will appear in the Astrophysical Journal.

Additional coauthors are from the University of California, Berkeley, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; Queen’s University Belfast; the University of Southampton; the University of California, Davis; Stockholm University; the Space Telescope Science Institute; the University of Minnesota; the University of California, Santa Barbara; and the Las Cumbres Observatory. The National Science Foundation, NASA, the European Research Council, and the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Council funded the research.

Source: University of Washington