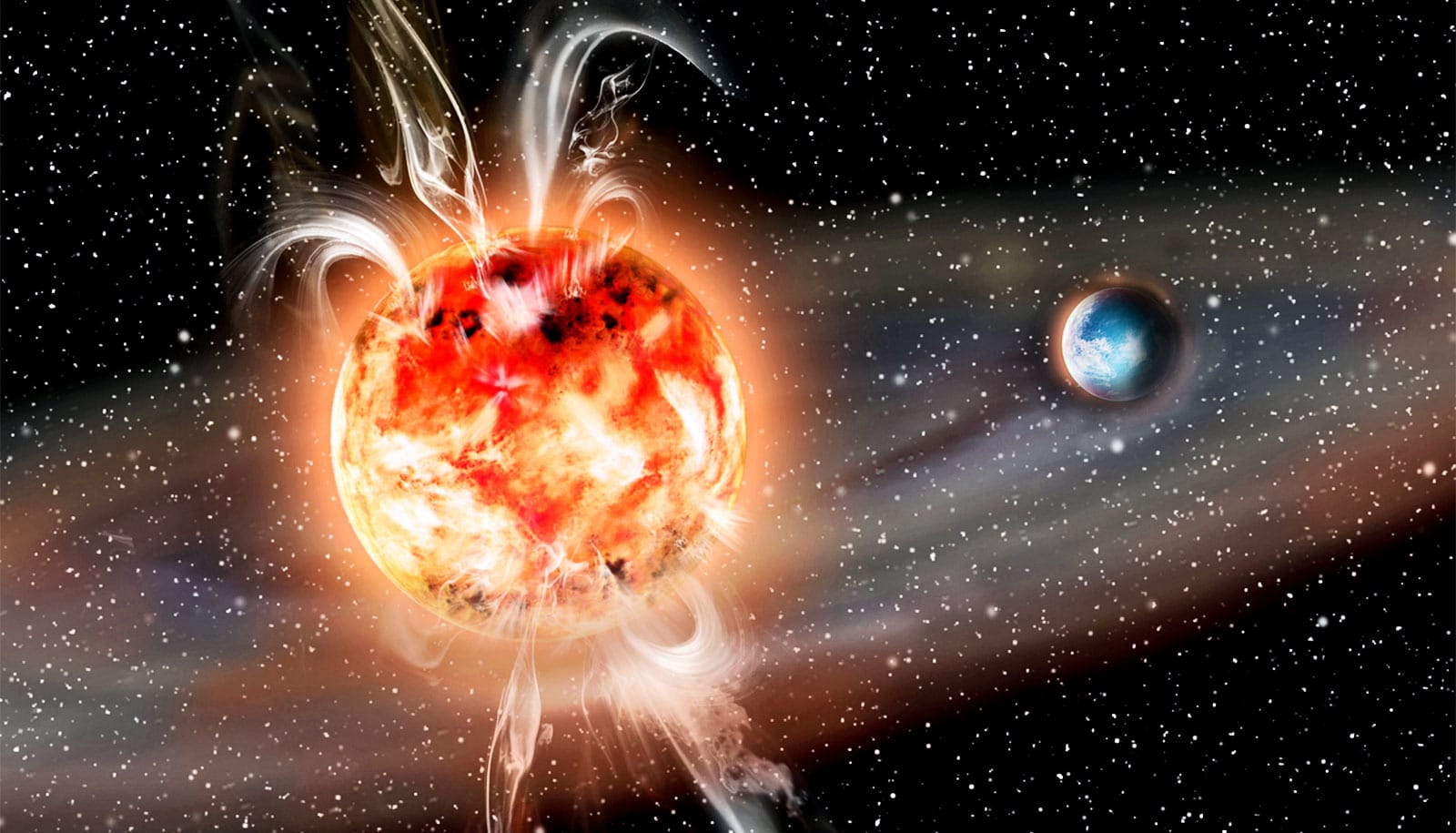

Superflares, extreme radiation bursts from stars, pose only a limited danger to the atmospheres—and thus habitability—of exoplanets, researchers report.

Astronomers have long suspected that they can cause lasting damage.

“We’ve known these are big flares, much larger than we see on our own sun,” says study coauthor James Davenport, a research assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Washington. “Now we see superflares occur at high latitudes, near the ‘poles’ of the star, which means that the bursts of radiation are not directed toward the paths of orbiting exoplanets.”

Hot flares and cool spots

Flares are magnetic explosions on the surface of stars that expel intense electromagnetic radiation into space. Large flares like superflares emit a cascade of energetic particles that can hit exoplanets orbiting the flaring star, and in the process alter or even evaporate planetary atmospheres.

Using optical observations from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite—or TESS—the team, led by astronomers at the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam, studied large superflares on red dwarfs, a class of young, small stars that have a lower temperature and mass than our own sun.

Many exoplanets have been found around these types of stars. A lingering question in exoplanet research has been whether they are habitable, since red dwarfs are more active than our sun and flare much more frequently and intensely.

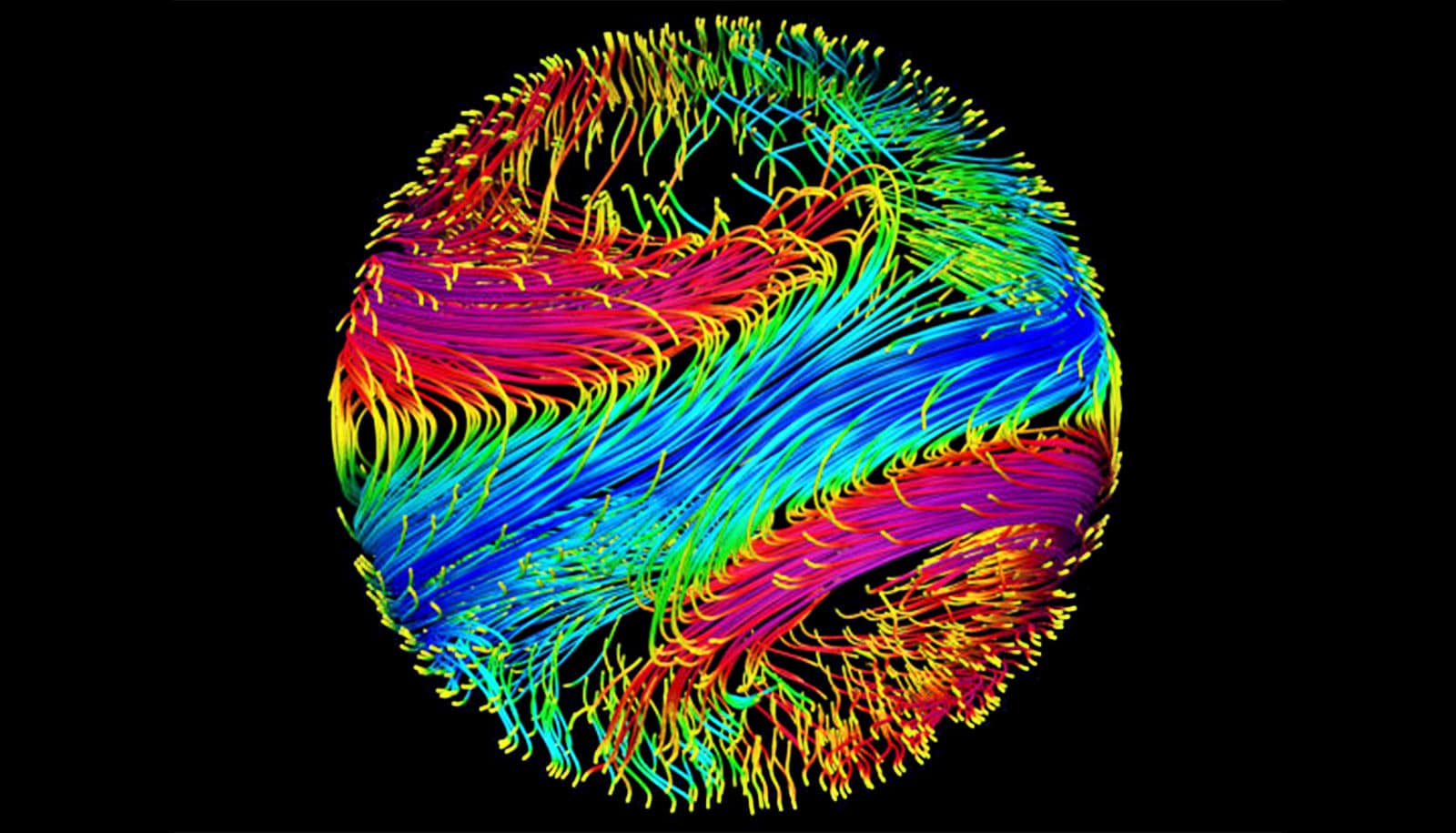

The team developed a method to determine the location on the stars’ surface where flares originate. To achieve this, the team analyzed so-called “whitelight flares” on fast-rotating red dwarf stars. These types of flares last long enough that their brightness, as observed by TESS, varies as they rotate in and out of view on the stellar surface.

“Since we can’t see the surfaces of these stars, determining the latitudes of things like hot flares and cool spots has traditionally been between difficult and impossible!” says Davenport, who is also the associate director of the Data Intensive Research in Astrophysics and Cosmology—or DiRAC—Institute at the University of Washington. “This work combines clever data modeling with the uniquely precise data that comes from missions like TESS, and finds something remarkable.”

The team found rotating flares by processing the light curves of more than 3,000 red dwarf stars by TESS. Among these stars, they found four with flares large enough for their new method. The team used the precise shape of each star’s light curve to infer the latitude of the flaring region, and found that all four flares occurred above approximately 55 degrees latitude, which is much closer to the pole than flares and spots on the surface of our sun, which usually occur below 30 degrees latitude. The team also showed that their detection method was not biased toward a particular stellar latitude.

Magnetic fields stronger than the sun

These findings, even with only four flares, are significant: If flares were spread equally across the stellar surface, the chances of finding four flares in a row at such high latitudes would be about 1-in-1,000.

This has implications for models of the magnetic fields of stars and for the habitability of exoplanets that orbit them.

“We discovered that extremely large flares are launched from near the poles of red dwarf stars, rather than from their equator, as is typically the case on the sun,” says lead author Ekaterina Ilin, a doctoral student at Leibniz.

“Exoplanets that orbit in the same plane as the equator of the star, like the planets in our own solar system, could therefore be largely protected from such superflares, as these are directed upwards or downwards out of the exoplanet system. This could improve the prospects for the habitability of exoplanets around small host stars, which would otherwise be much more endangered by the energetic radiation and particles associated with flares compared to planets in the solar system.”

The detection of these flares is further evidence that strong and dynamic concentrations of stellar magnetic fields, which can manifest themselves as dark spots and flares, form close to the rotational poles of fast-rotating stars. The existence of such “polar spots” has long been suspected from indirect reconstruction techniques like Doppler Imaging of stellar surfaces, but has not been detected directly so far.

“Nature is telling us something important about how these little, typically young stars produce magnetic fields that are much stronger than our sun,” says Davenport. “That has huge implications for how we think about the planets that orbit them.”

The study appears in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Additional coauthors are from Dartmouth College, the University of Colorado Boulder, the Canary Islands Astrophysics Institute, the University of La Laguna in Spain, the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam, and the University of Washington.

Source: University of Washington