For the first time, researchers have measured the light emitted by a sub-Neptune planet’s atmosphere.

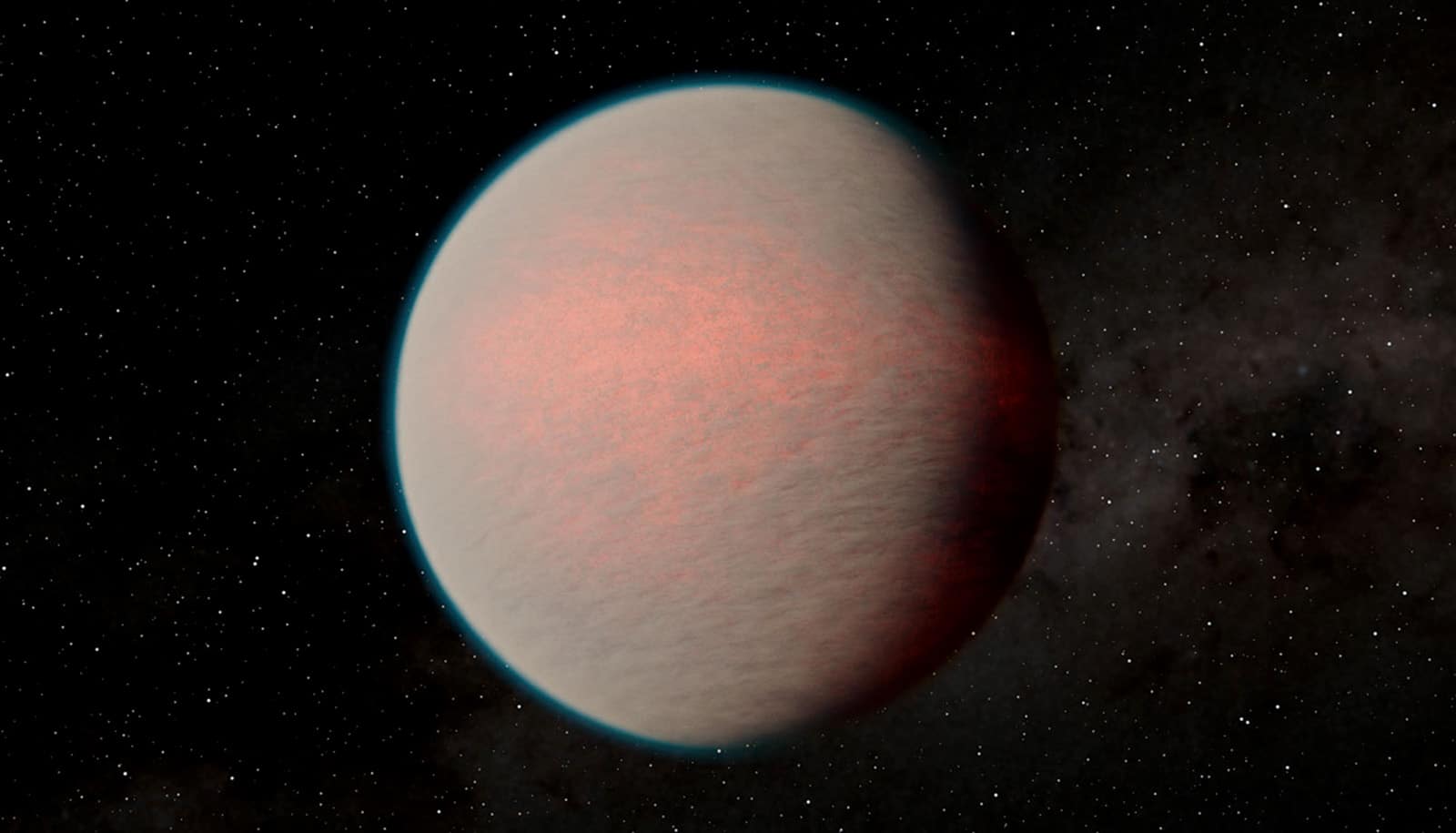

For more than a decade, astronomers have been trying to get a closer look at GJ 1214b, an exoplanet 40 light-years away from Earth.

Their biggest obstacle is a thick layer of haze that blankets the planet, shielding it from the probing eyes of space telescopes and stymying efforts to study its atmosphere. But now, NASA’s new JWST has solved that issue. The telescope’s infrared technology allows it to see planetary objects and features that were previously obscured by hazes, clouds, or space dust, aiding astronomers in their search for habitable planets and early galaxies.

A team of researchers from the University of Michigan and University of Maryland used JWST to observe GJ 1214b’s atmosphere by measuring the heat it emits while orbiting its host star. Their results, published in the journal Nature, represent the first time anyone has directly detected the light emitted by a sub-Neptune exoplanet—a category of planets that are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune.

Though GJ 1214b is far too hot to be habitable, researchers discovered that its atmosphere likely contains water vapor—possibly even significant amounts—and is primarily composed of molecules heavier than hydrogen.

Eliza Kempton, associate professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland and lead author of the study, says the findings mark a turning point in the study of sub-Neptune planets like GJ 1214b.

“I’ve been on a quest to understand GJ 1214b for more than a decade,” she says. “When we received the data for this Nature paper, we could see the light from the planet just disappear when it went behind its host star. That had never before been seen for this planet or for any other planet of its class, so JWST is really delivering on its promise.”

Sub-Neptunes and GJ 1214b

Sub-Neptunes are the most common type of planet in the Milky Way, though none exists in our solar system. Despite the murkiness of GJ 1214b’s atmosphere, the researchers determined the planet was still their best chance of observing a sub-Neptune’s atmosphere because of its bright but small host star.

In their study, they measured the infrared light that GJ 1214b emitted over the course of about 40 hours—the time it takes the planet to orbit its star. As day turns to night, the amount of heat that shifts from one side of a planet to the other depends largely on what its atmosphere is made of. Known as a phase curve observation, this research method opened a new window into the planet’s atmosphere.

University of Michigan graduate student Isaac Malsky, a coauthor of the study, ran three-dimensional models for the planet, testing models with and without clouds and hazes, to see how these aerosols shape the thermal structure of the planet and help interpret the data.

“These new data are extraordinary, and in conjunction with simulations they inform our understanding that GJ 1214 b likely has a metal-enhanced atmosphere. With JWST we were able to see changes in the planet’s brightness over the course of the observation, revealing new slices of the planet throughout its orbit,” Malsky says.

“Running models allows us to test different scenarios and see how they compare to the observations, as well as explore how different effects, like hazes or clouds, influence the planet and manifest in observables.”

By measuring the movement and fluctuation of heat, the researchers determined that GJ 1214b does not have an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen.

“Previously all we knew about this planet was that it was blanketed in thick aerosols. Now with these new findings we can confidently say that the atmosphere is not dominated by hydrogen and helium, like Jupiter, but is primarily composed of heavier species, such as water,” says study coauthor Emily Rauscher, associate professor at the University of Michigan.

Is GJ 1214b a ‘water world’?

The question of whether GJ 1214b contains water has long interested astronomers. Previous observations by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope suggested that GJ 1214b could be a water world—a loose term for any planet that contains a significant amount of water.

The latest JWST data reveal traces of water, methane, or some mix of the two. These substances match a subtle absorption of light seen in the wavelength range observed by JWST. Further studies will be needed to determine the exact makeup of the planet’s atmosphere, but the evidence remains consistent with the possibility of large amounts of water, the researchers say.

“Additionally, it’s possible that GJ 1214 may be what’s known as a ‘water world,’ which means that water makes up a large portion of the planet’s bulk composition,” Malsky says. “This scenario would be consistent with the data collected, and is a fascinating alternative hypothesis.”

Surprising reflection

The researchers made another surprising discovery in their study: GJ 1214b is incredibly reflective. The planet was not as hot as expected, which tells researchers that something in the atmosphere is reflecting light.

Kempton says there is plenty of room for follow-up studies, including ones that take a closer look at the high-altitude aerosols that form the haze—or possibly clouds—in GJ 1214 b’s atmosphere. Previously, researchers thought it might be a dark, soot-like substance that absorbs light. However, the discovery that the exoplanet is reflective raises new questions.

“We also were surprised to learn that the aerosols blanketing the planet are highly reflective, much more than anything we were expecting,” Rauscher says. “So while we know more about the planet’s atmosphere, we’ve also discovered a new mystery.”

Source: Emily Nuñez for the University of Maryland, University of Michigan