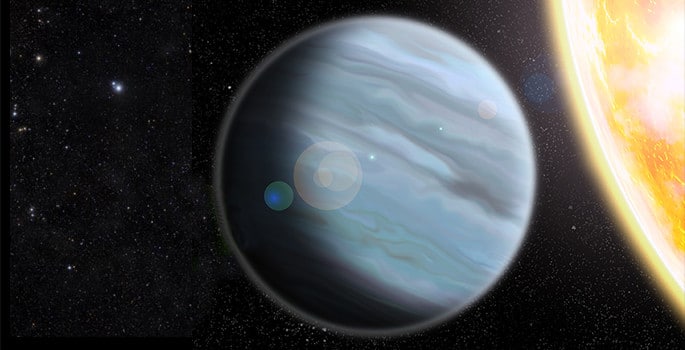

Astronomers have discovered a new planet orbiting a star 320 light years from Earth with the same density as Styrofoam. The “puffy planet” may provide opportunities for testing atmospheres that will be useful when assessing future planets beyond our solar system for signs of life.

“It is highly inflated, so that while it’s only one fifth the mass of Jupiter, it is nearly 40 percent larger, making it about as dense as Styrofoam, with an extraordinarily large atmosphere,” says Joshua Pepper, assistant professor of physics at Lehigh University and leader of the study in the Astronomical Journal.

Astronomers have only found two other exoplanets with precisely measured masses and radii that have lower densities than the newly discovered planet, designated KELT-11b.

The planet’s host star is extremely bright, allowing precise measurement of the properties of the planet’s atmosphere making it “an excellent test-bed for measuring the atmospheres of other planets,” Pepper says. Such observations help astronomers develop tools to see the types of gases in atmospheres, which will be necessary in the next 10 years when they apply similar techniques to Earth-like exoplanets with next-generation telescopes that are now under construction.

Hunt for life on exoplanets gets new tools

KELT-11b is an extreme version of a gas planet, like Jupiter or Saturn, but is orbiting very close to its host star with an orbital period less than five days. Its host star, KELT-11, has started using up its nuclear fuel and is evolving into a red giant, so the planet will be engulfed by its star in the next hundred million years and won’t survive.

The unusual exoplanet was discovered by the KELT (Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope) survey, which uses two small robotic telescopes, one in Arizona and the other in South Africa. The low-cost telescopes scan the sky night after night, measuring the brightness of about five million stars. Researchers search for stars that seem to dim slightly at regular intervals, which can indicate a planet is orbiting that star and eclipsing it.

They then use other telescopes to measure the gravitational “wobble” of the star–the slight tug a planet exerts on the star as it orbits—to verify that the dimming is due to a planet and to measure the planet’s mass.

Color key to aid search for life on exoplanets

“When we initiated the KELT project, it was with the hope that we would find exoplanets like KELT-11b, whose atmospheres are puffy and whose host stars are very bright,” says Keivan Stassun, professor of physics at Vanderbilt University.

“Just the right combination to permit lots of starlight to percolate through a thin atmosphere, eventually telling us what these other-worldly atmospheres are made of and even what their weather patterns are like.”

The KELT telescopes are specifically designed to discover scientifically valuable planets orbiting very bright stars. KELT-11 is the brightest star in the southern hemisphere known to host a transiting planet and the sixth brightest transit host discovered to date.

Scott Gaudi, associate professor of astronomy at Ohio State University, is a coauthor of the study. The National Science Foundation and NASA funded the work, along with support from a number of participating universities and foundations.

Source: Vanderbilt University