Black patients are significantly less likely than white patients to receive the gold standard of stroke care, according to new research.

Almost 800,000 Americans suffer a stroke each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

African Americans and other people of color have a substantially higher risk of experiencing a stroke than their white counterparts. And they’re also significantly more likely to die from those strokes.

“Racial disparities exist in all levels of stroke care,” says Delaney Metcalf, a third-year medical student in the Augusta University/University of Georgia Medical Partnership and lead author of the study in the Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases.

“There are many studies that show quality of medical care in general can be poorer in minority populations. But as health care professionals, we are not doing a good enough job of getting these lifesaving treatments to these patients.”

The researchers analyzed data from more than 89,000 stroke patients across the US and found that Black patients were significantly less likely to receive tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a clot-busting medication that helps restore blood flow to the brain after a stroke.

Additionally, Black patients were less likely than white patients to undergo endovascular thrombectomy (EVT), a minimally invasive procedure in which the blood clot is surgically removed.

When minority patients do get needed treatment, the researchers found non-white patients had substantially longer hospital stays, which may signify poorer health outcomes or lower quality of care.

tPA and EVT are the go-to medical treatments for ischemic strokes, which are caused by blood clots. They dramatically reduce death after a stroke and lead to significantly better health outcomes.

But both options are extremely time sensitive.

To be effective, tPA should be given within a few hours of a stroke. And patients requiring the EVT surgical procedure need to be on the table within about six hours. For rural patients or those living in underserved areas, that’s a tall ask.

Previous research has shown that Black and minority patients are less likely to call emergency services for an ambulance, which can delay medical care significantly.

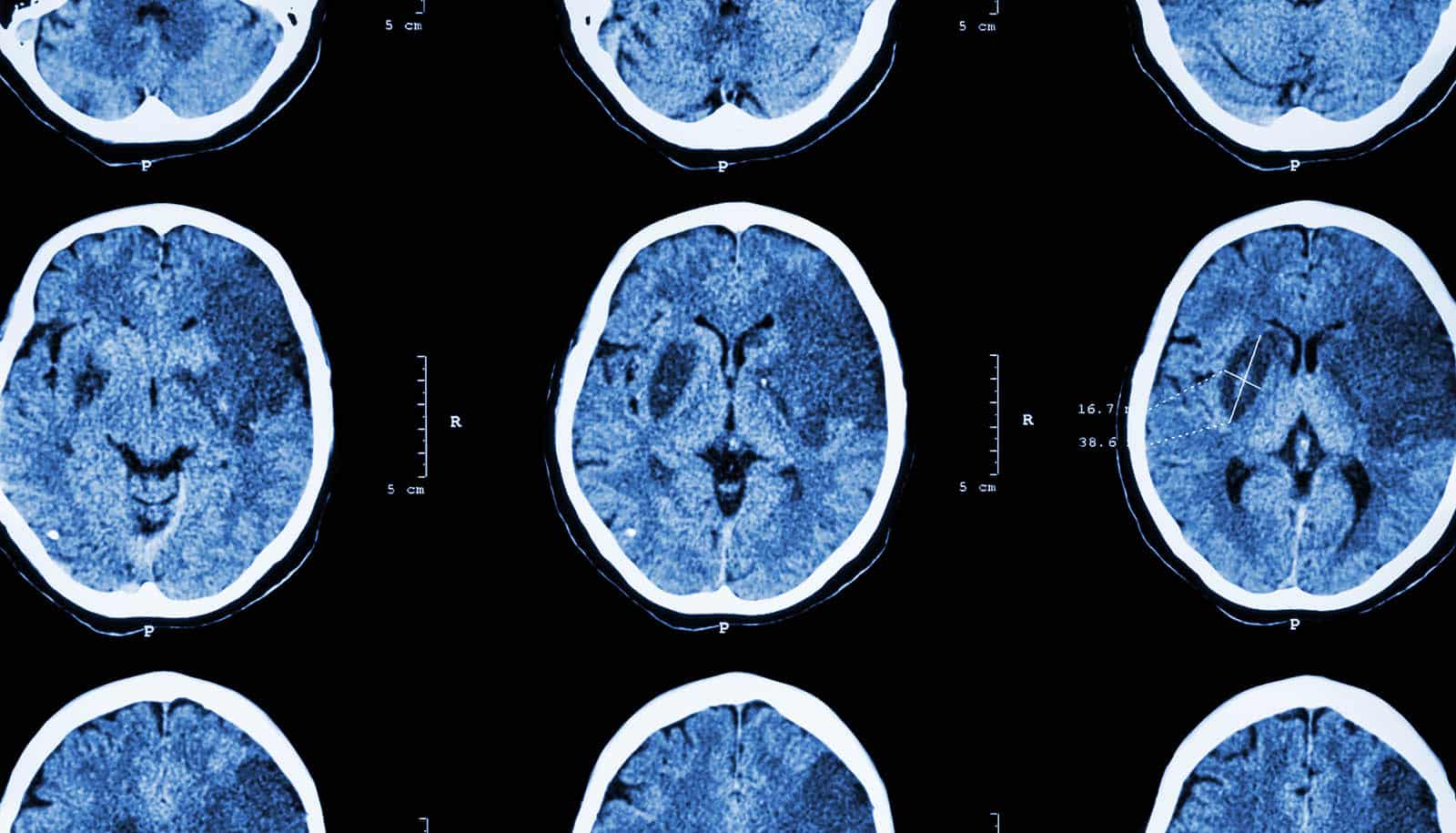

But even once they arrive, Black and minority patients experience longer wait times to be seen by health care providers to get brain imaging. Brain scans are necessary to determine a treatment course.

“Why is that? It could be that the hospital is really overrun and doesn’t have the staff to be able to do it in a timely manner,” Metcalf says. “There can also be implicit racial biases that lead to health professionals not treating their Black patients the same way they treat their white patients and not taking minority patients’ symptoms seriously.”

And not every hospital has the staff, medicine, and equipment to make sure stroke patients receive this specialized care. That lack of access can have deadly consequences.

“This is a problem, but it’s a targetable problem,” Metcalf says. “Increasing education on what a stroke looks and feels like is one tiny thing we can make an improvement on.

“There are many small things we can do to make advances in minority stroke care. Increasing community education on recognizing stroke symptoms may help patients get to treatment centers faster. Additionally, providing the training and technology needed for these treatments to underserved areas can improve access to stroke care.”

Donglan Zhang, a former assistant professor at the University of Georgia now at NYU Long Island School of Medicine, is the study’s coauthor.

Source: University of Georgia