Stonefishes—some of the deadliest, armored fishes on the planet—are packing switchblades called “lachrymal sabers” in their faces, new research shows.

Now, a new study details the evolution of the lachrymal saber unique to stonefishes—a group of rare and dangerous fishes inhabiting Indo-Pacific coastal waters. The new finding rewrites scientific understanding of relationships among several groups of fishes, reveals a previously unknown defensive strategy, and will likely fuel a few nightmares.

“I don’t why this hasn’t been discovered before,” says William Leo Smith, associate professor of ecology & evolutionary biology and associate curator at the Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum at the University of Kansas.

“It’s probably because there are just one or two people that ever worked on this group. We took five or six families and were able to resolve the problems in their classifications. To have this really strong anatomical feature visible from the outside is really helpful. To have a big map of how everything is related and evidence for it is what we’re all hoping for. We have this feature and get into the genetics of how it could have evolved.”

Close relatives

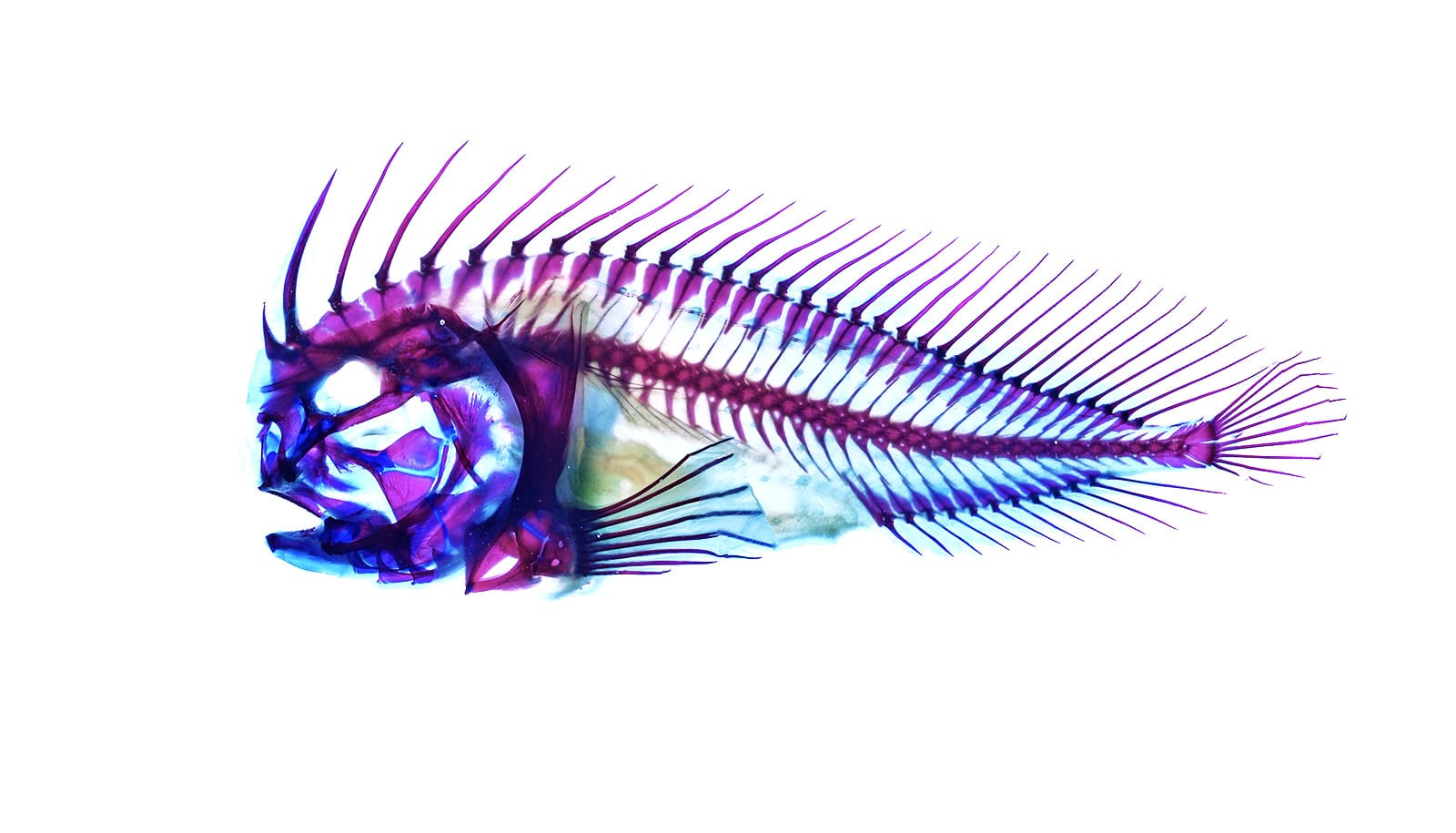

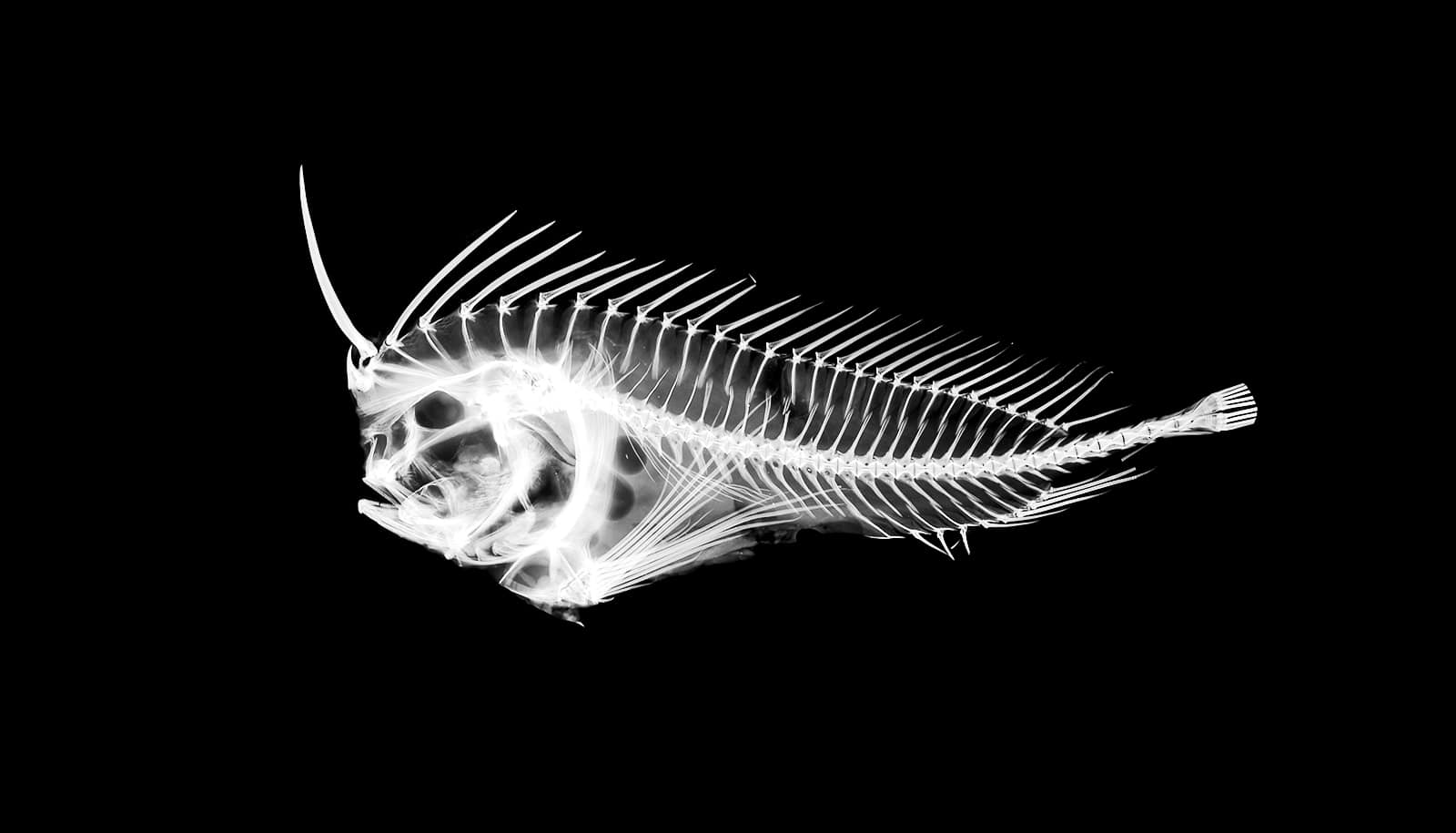

All stonefishes examined for the study have a lachrymal saber on each cheek below the eye. Moreover, genetic analysis of 113 morphological and 5,280 molecular characters for 63 species reveals stonefishes possessing the lachrymal saber are closely related, producing a revised taxonomy of flatheads, scorpionfishes, sea robins, and stonefishes.

The switchblade-like devices in the cheeks of stonefish involve specialized modifications to several bones and muscles: the circumorbitals, maxilla, and adductor mandibulae.

As reported in the journal Copeia, the research began 15 years ago when Smith was dissecting a stonefish that had been his own pet—he became the first researcher to understand the locking switchblade mechanism and how it worked anatomically.

“The outermost bone has a little peg, or a bump, or is heavily grooved. It is called the lachrymal and forms the bony ring around the fish’s eye, and the underlying bone looks like it has a roly poly bug on it and is called the maxilla, part of the upper jaw—in most land vertebrates the maxilla would be toothed,” he says.

“This roly poly piece of the switchblade is the first thing I saw when I started dissecting and recognized this mechanism—these two roly poly things sit on top of each other and can ratchet at different levels. It can lock out all the way or can lock out at different places.”

Mighty mouth

To help the stonefishes deploy the switchblade, an unusually large number of muscles and ligaments attach to bones comprising the lachrymal saber system compared with species outside the stonefish family, Smith says.

“There can’t be any other reason for those muscles and ligaments except to control this mechanism. This whole group of fishes is called the ‘mail cheek fishes’ or Scorpaeniformes, where the bones under the eye attach to the gill skeleton. Because all these muscles are attached to the gill skeleton, it allows for all this force which causes the lachrymal saber to deploy.”

Smith says the switchblade only adds to an already impressive array of defensive features that rank stonefishes among the deadliest fishes in the ocean, including spikes, camouflages, and some of the world’s most powerful venoms, which could even be fatal to an adult human being.

Hagfishes use skin and slime to survive attack

“Of all the fishes I’ve studied, I haven’t yet been stung by any of these stonefishes,” Smith says. “I’m just super paranoid. In some places they catch them for food—the big ones, they’re delicious—there is an aquaculture for larger ones in Indonesia. That’s mind-boggling to me. The venom breaks down in our digestive system. But people eat lots of venomous species all over the world, even in the US.”

The lachrymal saber is most likely an additional defensive system in stonefishes, to avoid predation.

“If you find pictures of these stonefishes in the mouths of other things, the lachrymal saber is always locked out,” he says. “The main thing people know about these fishes is they’re venomous. Some people know them because they have these fingerlike appendages and drag themselves around like they’re playing the piano. The appendages actually taste food as they go.

“These stonefishes can mimic leaves floating in the water—they’re super camouflaged. A lot of them have really bright pectoral fins on sides of their body, and when they’re scared they flash them—this drab fish will suddenly flash bright yellows and oranges. I always assume all of these features are defensive, but recent studies by other fish scientists suggest these could all be displays like a peacock.”

Researchers collected some of the specimens examined as part of the study in the pet-fish trade and others during fieldwork in Taiwan during which they used the enormity of the Taiwanese fishing industry to their advantage.

“We had a trip to Taiwan three years ago where we caught 1 percent of all fish species worldwide,” Smith says. “You can get deep-sea and shallow-water fish because it’s a volcanic island—and they send out a zillion boats to get shrimp—their fishing industry is supported like our agricultural industry.

These fish eat the scales they ram or pry off others

“You don’t have to rent boats for research, you can sit on a dock and go through the fishes, they’re going to just grind up and essentially, so we can collect these samples for free.”

Source: University of Kansas