Asian Americans, particularly Korean Americans, are at an unusually high risk for stomach cancer, research shows.

Over the last six decades in the United States, stomach, or gastric, cancer rates have plummeted. But around the world, gastric cancer remains a leading cause of death, particularly in Asia.

In an article in the journal Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Joo Ha Hwang, a professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Stanford Medicine, reviews the literature on gastric cancer rates. Hwang is the director of strategy at the Center for Asian Health Research and Education, which seeks to improve the health of Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander populations.

Hwang discusses the disparity that exists in gastric cancer between Asian Americans and other Americans, why it exists, and how to address it:

Your study revealed that Asian people are more likely to have gastric cancer than any other group. What does the data say?

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of death throughout the world. In the US, the rate is much lower. But Asians represent only about 6% of the US population, although they represent 60% of the world population. Asian populations are at a particularly high risk for gastric cancer, even if they’re living in the US.

California is unique in that the public health system keeps track of health data by ethnicity. Within California, we know that Koreans, Vietnamese, Japanese, and Chinese people have a substantially higher risk of gastric cancer. Korean people, for instance, see the greatest increase in risk at 13 times that of non-Hispanic white people, whose risk is roughly 9 in 100,000. Vietnamese people’s risk is 7 times that of non-Hispanic white people, and Japanese and Chinese people have a risk that’s about 5 times higher.

Unfortunately, in the US, we tend to aggregate everybody and say gastric cancer isn’t a big threat, and that really puts minority groups at a strong disadvantage.

What’s behind the greater risk in Asian populations?

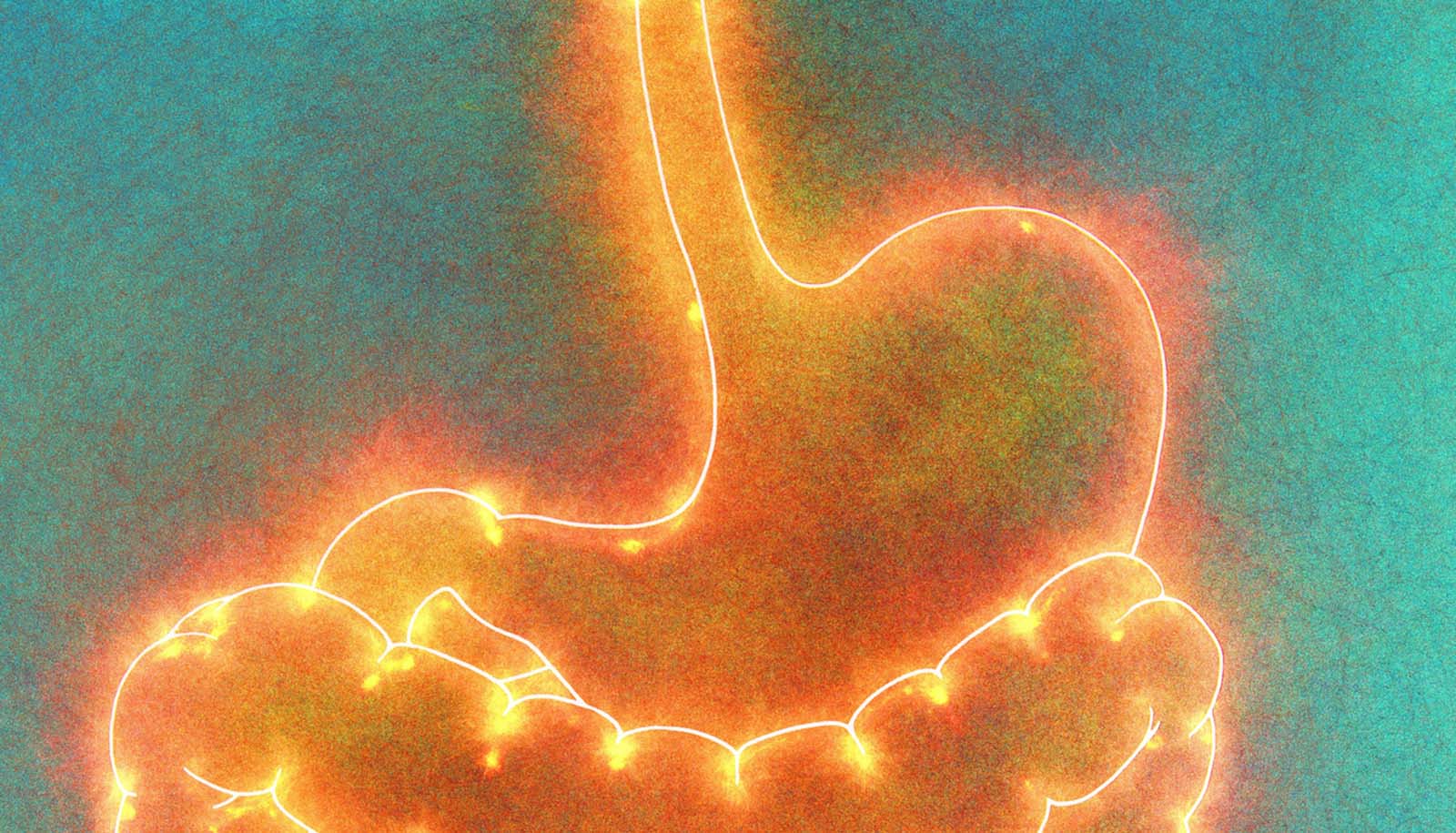

Helicobacter pylori is a bacterium that can infect and inflame the stomach. But it can be a relatively asymptomatic infection, which is why it often goes undetected. If someone has H. pylori for decades, they develop chronic inflammation, which can contribute to cancer. The World Health Organization considers it a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning there is strong scientific evidence that H. pylori causes cancer.

The prevalence of H. pylori infection is much higher in Asia and other parts of the world. Why it’s so high is unknown. The rate of H. pylori infection in the US is only about 10% to 20% for all populations, whereas in Asian countries, it is as high as 80%. We know that recent immigrants in high-incidence countries are at high risk, but we don’t have good data on children of immigrant parents.

What is the role of cancer screening in closing the disparity?

Japan and Korea have national stomach cancer screening programs because the incidence of gastric cancer is so high. If you identify gastric cancer early, it can be treated. In the US, because we don’t screen as often and catch it early, only 30% of patients who are diagnosed with stomach cancer reach the five-year survival mark. In Japan and Korea, the survival rate at five years is 60% to 70%.

We’re trying to implement a similar program at the Center for Asian Health Research and Education. We gather information about patient ethnicity, family history, genetics, and prior history of H. pylori infection, then determine if the person is a good candidate for a screening endoscopy, in which a small sample of tissue is removed from the gastrointestinal tract for inspection.

What we’re proposing is that we should be testing for H. pylori in high-risk populations at a younger age, before the chronic inflammation and damage occurs and we theoretically can prevent stomach cancer. Once you know a patient has it, H. pylori is a very treatable bacterial infection.

What can be done—on an individual and systematic level—to address the elevated risk for gastric cancer in Asian populations?

A lot of it is education. People who are at high risk should be told so they can talk with their doctors about it. Even in the Bay Area, where there’s a large percentage of Asian and Asian American patients and doctors, many don’t know that they and other Asians and Asian Americans are at higher risk for this cancer. I bring attention to that fact as often as I can.

We’re also trying to change health policies. We’re trying to educate not just our representatives, but also other societies. We are trying to educate the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the American Cancer Society so that they can help to write guidelines to direct clinical care to screen and survey patients who are at high risk of developing gastric cancer. We’re also trying to increase funding for gastric cancer research, the most underfunded sector of cancer research in the country.

We recently had a large gastric cancer summit at Stanford, where members of the National Institutes of Health and cancer experts from all over the world came to talk about how to improve outcomes for gastric cancer in the US We’re making progress. It’s slow, but education is a big part of making a difference.

Source: Stanford University