A new camera could prevent companies from collecting embarrassing and identifiable photos and videos from devices like smart home cameras and robotic vacuums.

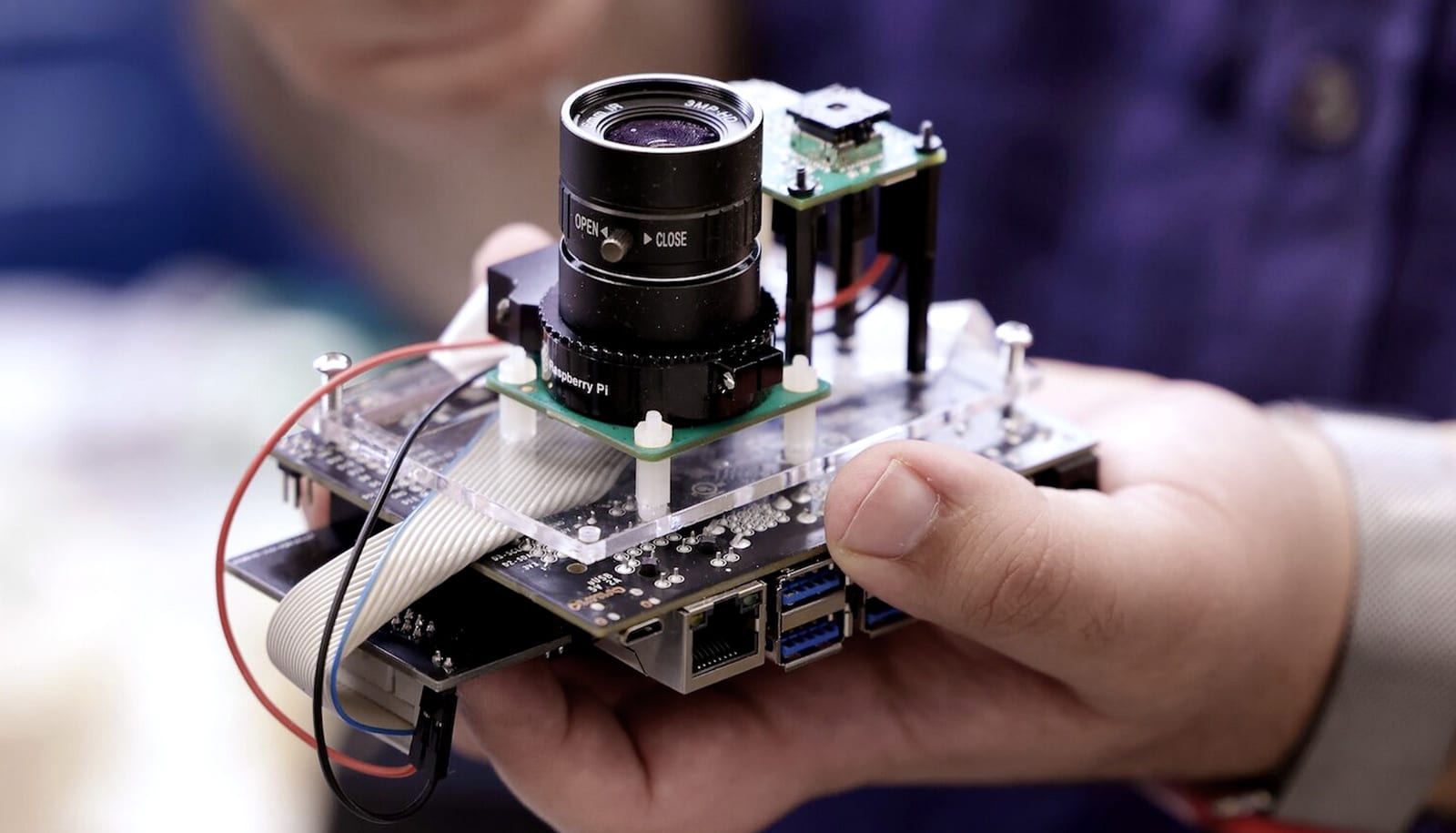

The camera, called PrivacyLens, uses both a standard video camera and a heat-sensing camera to spot people in images from their body temperature. The person’s likeness is then completely replaced by a generic stick figure, whose movements mirror those of the person it stands in for.

The accurately animated stick figure allows a device relying on the camera to continue to function without revealing the identity of the person in view of the camera.

That extra anonymity could prevent private moments from leaking onto the internet, which is increasingly common in today’s world laden with camera-equipped devices that collect and upload information.

In 2020, a photo of a person on the toilet appeared on an online forum. The person didn’t realize their iRobot Roomba had wandered into the bathroom, and that all its photos were sent to a start-up company’s cloud server. From there, the photos were accessed and shared on social media groups, according to an investigation by MIT Technology Review.

“Most consumers do not think about what happens to the data collected by their favorite smart home devices. In most cases, raw audio, images, and videos are being streamed off these devices to the manufacturers’ cloud-based servers, regardless of whether or not the data is actually needed for the end application,” says Alanson Sample, associate professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Michigan and corresponding author of the study.

“A smart device that removes personally identifiable information before sensitive data is sent to private servers will be a far safer product than what we currently have.”

Raw photos are never stored anywhere on the device or in the cloud, completely eliminating access to unprocessed images. With this level of privacy protection, the engineering team hopes to make patients more comfortable with using cameras to monitor chronic health conditions and fitness at home.

“Cameras provide rich information to monitor health. It could help track exercise habits and other activities of daily living, or call for help when an elderly person falls,” says Yasha Iravantchi, a doctoral student in computer science and engineering who will present PrivacyLens at the Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium in Bristol, UK.

“But this presents an ethical dilemma for people who would benefit from this technology. Without privacy mitigations, we present a situation where they must weigh giving up their privacy in exchange for good chronic care. This device could allow us to get valuable medical data while preserving patient privacy.”

Replacing patients with stick figures helps make them more comfortable having a camera in even the most private parts of the home, according to an initial survey of 15 participants. The team has incorporated a sliding privacy scale into the device that allows users to control how much of their faces and bodies are censored.

“Our survey suggested that people might feel comfortable only blurring their face when in the kitchen, but in other parts of the home they may want their whole body removed from the image,” Sample says. “We want to give people control over their private information and who has access to it.”

The device could not only make patients more comfortable with chronic health monitoring, but it could also help protect privacy in public spaces. Vehicle manufacturers could potentially use PrivacyLens to prevent their autonomous vehicles from being used as surveillance drones, and companies that use cameras to collect data outdoors might find the device useful for complying with privacy laws.

“There’s a wide range of tasks where we want to know when people are present and what they are doing, but capturing their identity isn’t helpful in performing the task. So why risk it?” Iravantchi says.

The Rackham Graduate School and a Meta faculty research gift funded the work.

Sample has filed a provisional patent for the device, with the help of University of Michigan Innovation Partnerships, and hopes to eventually bring it to market.

Source: Derek Smith for University of Michigan