To evaluate closeness in stepfamilies, researchers measured how much time they spend together.

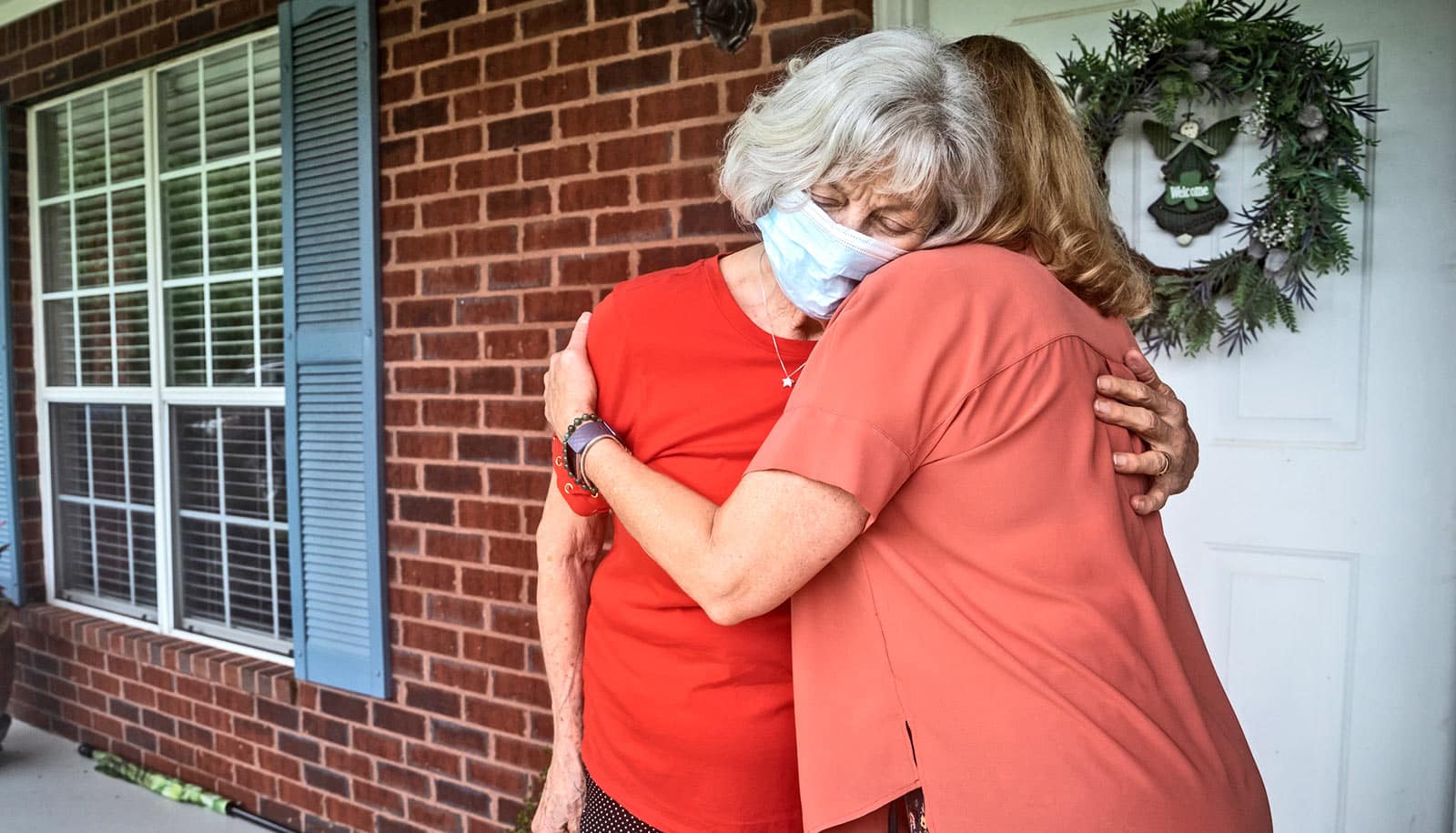

Researchers have been concerned that as the makeup of America’s families grows more complex, adult children in stepfamilies may not be as willing as those in biological families to care for aging parents.

The researchers’ findings, published in the journal Demography, challenge the view that ties with older parents are always weaker with stepchildren in stepfamilies, and point to an important, though relatively uncommon, exception, says Vicki Freedman, research professor in the Survey Research Center at University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research and one of the study’s authors.

Previous studies have found that stepfamilies have weaker ties than biological families, and that the ties between a stepparent and stepchild are weaker than those between a biological parent and biological child. But, with few exceptions, these studies only compared stepfamilies to biological families without considering whether the partners in stepfamilies had a biological child together.

For the current study, researchers hypothesized that the strength of family ties depends on both the structure of the family and the nature of the relationships between parents and adult children within those family structures.

The researchers compared biological families to stepfamilies in which the married or cohabiting parents each have biological children from previous unions; stepfamilies in which just one parent has children from a previous union; and stepfamilies who have children from previous unions as well as at least one joint biological child.

They also compared different types of parent-child ties within the various family types. They found that an older parent’s tie with a joint child is stronger in stepfamilies than in biological families. Within stepfamilies, ties are only stronger between a parent and biological child—compared to a stepchild—in Brady Bunch-like families, in which each partner has at least one biological child from previous relationships and there are no joint children.

“Why ties are similar in stepfamilies that include a joint child and biological families is puzzling. Stepfamilies with joint children are more likely to live together than biological families, but whether they live together because their ties are stronger or vice versa is not clear,” says Freedman, also director of the Michigan Center on the Demography of Aging. “We need to understand more about the implications of the complexities of America’s families especially in light of the aging of the population.”

To assess the strength of familial bonds, the researchers used a previously untapped indicator: time spent together yesterday, measured by time diaries. These time diaries were collected as a supplemental interview administered to a subset of older participants in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, a national longitudinal survey that began in 1968 with about 18,000 participants in 5,000 households. The study collects information such as employment, income, wealth, expenditures, health, marriage, education, and childbearing, among many other topics. In 2013, detailed information on biological and step relationships within families was collected.

The researchers analyzed more than 2,000 daily time diaries, which detailed the time older parents spent with their adult children on the previous day, as well as information in the main interview about biological and step relationships in the family.

They found that about 35% of parents in biological families reported spending time with adult children on the previous day, a figure higher than that for stepfamily configurations with no joint children. Nearly half of parents—47%—with both joint and stepchildren reported spending time with their children.

Interestingly, the amount of time spent together was similar for biological families and stepfamilies with both joint and stepchildren—about 4 to 5 hours on average on days when family time occurred. In contrast, stepfamilies with no joint children spent about 2.5 to 3 hours on average on days when time together took place.

The researchers say there is an important caveat: Stepfamilies with joint biological children are not especially common. About 65% of older parents have biological families, whereas only 7% of older parents have stepfamilies that include a joint biological child. The remaining 28% of older parents have stepfamilies with weaker ties, as evidenced by being less likely to spend time together.

Stronger intergenerational ties within families can benefit individuals and society through care provided to aging parents, childcare given by grandparents, and other forms of support.

“It is possible that norms regarding such support may shift as stepfamilies become more common,” says coauthor Judith Seltzer, research professor at UCLA’s California Center for Population Research. “Whether these types of stepfamilies with stronger ties will become more or less common over time is an important outstanding question for family demographers.”

Support for this research came from the National Institute on Aging and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: University of Michigan