A “great” space weather super-storm—large enough to cause significant disruption to our electronic and networked systems—occurred on average once every 25 years, according to a new study.

By analyzing magnetic field records at opposite ends of the Earth (the UK and Australia), scientists have been able to detect super-storms going back over the last 150 years.

This result is possible due to a new way of analyzing historical data from the last 14 solar cycles, way before the space age began in 1957, instead of just the last five.

Typically, a storm may only last a few days but can be hugely disruptive to modern technology. Super-storms can cause power blackouts, take out satellites, disrupt aviation, and cause temporary loss of GPS signals and radio communications.

“These super-storms are rare events but estimating their chance of occurrence is an important part of planning the level of mitigation needed to protect critical national infrastructure,” says lead author Sandra Chapman, a professor at the University of Warwick’s Centre for Fusion, Space, and Astrophysics.

“This research proposes a new method to approach historical data, to provide a better picture of the chance of occurrence of super-storms and what super-storm activity we are likely to see in the future.”

The Carrington storm of 1859 is widely recognized as the largest super-storm on record, but predates even the data used in this study. The analysis Chapman led estimates what amplitude the storm would need to have been to be in the same class as the other super-storms—and hence with a chance of occurrence that researchers can estimate.

“Our research shows that a super-storm can happen more often than we thought,” says Richard Horne, a professor who leads Space Weather at the British Antarctic Survey. “Don’t be misled by the stats, it can happen any time, we simply don’t know when and right now we can’t predict when.”

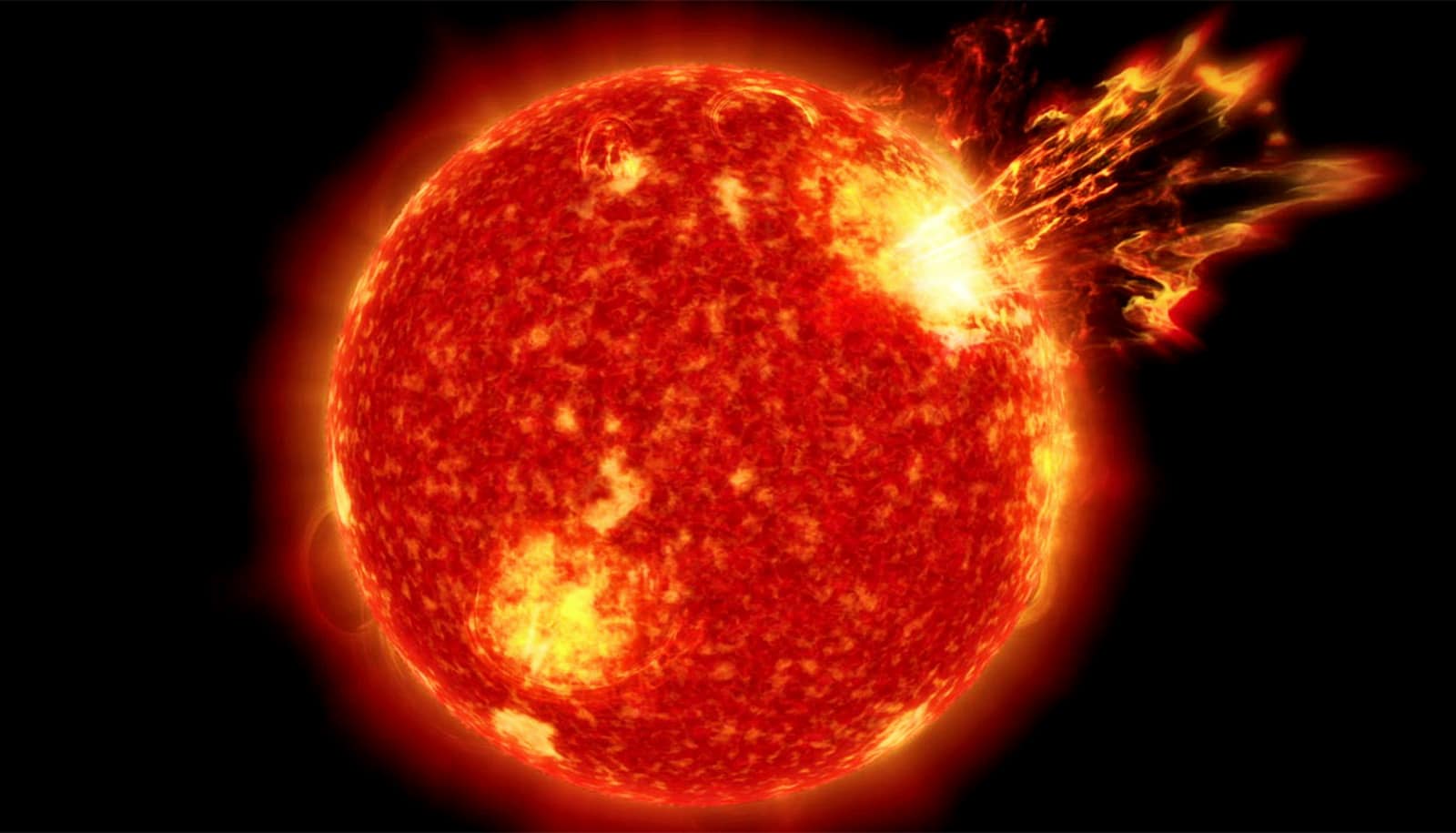

Activity from the sun drives space weather. Smaller scale storms are common, but occasionally larger storms occur that can have a significant impact.

Observing changes in the magnetic field at the Earth’s surface is one way to monitor this space weather. High quality observations at multiple stations have been available since the beginning of the space age (1957). The sun has an approximately 11-year cycle of activity which varies in intensity and this data, which has been extensively studied, covers only five cycles of solar activity.

If we want a better estimate of the chance of occurrence of the largest space storms over many solar cycles, we need to go back further in time. Scientists derived the aa geomagnetic index from two stations at opposite ends of the Earth to cancel out Earth’s own background field. This goes back over 14 solar cycles or 150 years, but has poor resolution.

Using annual averages of the top few percent of the aa index the researchers found that a “severe” super-storm occurred in 42 years out of 150 (28%), while a “great” super-storm occurred in 6 years out of 150 (4%) or once in every 25 years. As an example, the 1989 storm that caused a major power blackout of Quebec was a great storm.

In 2012, the Earth narrowly avoided trouble when a coronal mass ejection from the sun missed the Earth and went off in another direction. According to satellite measurements, if it had hit the Earth it would have caused a super-storm.

The research, which involved researchers from the British Antarctic Survey, appears in Geophysical Research Letters.

Source: University of Warwick