X-ray computed tomography offers a real-time view of how cracks form near the edges of the interfaces between materials in solid-state batteries.

The findings could help researchers find ways to improve the energy storage devices.

Solid-state batteries—a new battery design that uses all solid components—have gained attention in recent years because of their potential to hold much more energy while simultaneously avoiding the safety challenges of their liquid-based counterparts.

The power of solid-state batteries

“Solid-state batteries could be safer than lithium-ion batteries and potentially hold more energy, which would be ideal for electric vehicles and even electric aircraft,” says Matthew McDowell, an assistant professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Materials Science and Engineering at the Georgia Institute for Technology. “Technologically, it’s a very fast moving field, and there are a lot of companies interested in this.”

In a typical lithium-ion battery, energy is released during the transfer of lithium ions between two electrodes—a cathode and an anode—through a liquid electrolyte.

For the study, the research team built a solid-state battery in which they sandwiched a solid ceramic disc between two pieces of solid lithium. The ceramic disc replaced the typical liquid electrolyte.

“Figuring out how to make these solid pieces fit together and behave well over long periods of time is the challenge,” McDowell says. “We’re working on how to engineer these interfaces between these solid pieces to make them last as long as possible.”

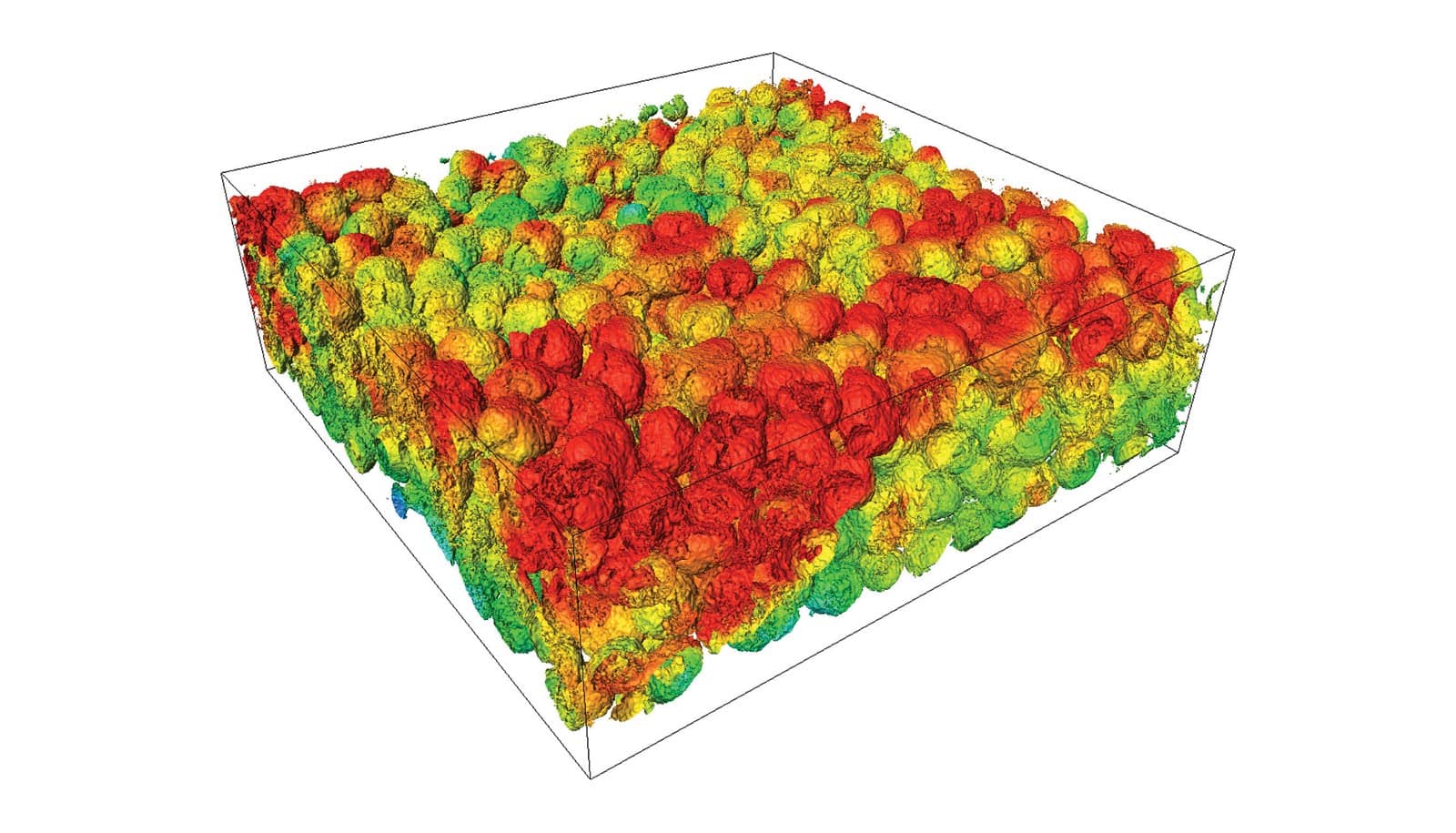

The researchers placed the battery under an X-ray microscope and charged and discharged it, looking for physical changes indicative of degradation. Slowly over the course of several days, a web-like pattern of cracks formed throughout the disc.

Pesky fractures

Those cracks are the problem and occur alongside the growth of an interphase layer between the lithium metal and solid electrolyte. The researchers found that this fracture during cycling causes resistance to the flow of ions.

“These are unwanted chemical reactions that occur at the interfaces,” McDowell says. “People have generally assumed that these chemical reactions are the cause the degradation of the cell. But what we learned by doing this imaging is that in this particular material, it’s not the chemical reactions themselves that are bad—they don’t affect the performance of the battery. What’s bad is that the cell fractures, and that destroys the performance of the cell.”

Solving the fracturing problem could be one of the first steps to unlocking the potential of solid state batteries, including their high energy density. The deterioration observed is likely to affect other types of solid-state batteries, the researchers note, so the findings could lead to the design of more durable interfaces.

“In normal lithium-ion batteries, the materials we use define how much energy we can store,” McDowell says. “Pure lithium can hold the most, but it doesn’t work well with liquid electrolyte. But if you could use solid lithium with a solid electrolyte, that would be the holy grail of energy density.”

The research appears in the journal ACS Energy Letters.

The National Science Foundation supported the research. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors.

Source: Georgia Tech